Is there a property bubble in China?

China admirably withstood the Great Recession that hit the global economy in 2008-2009. However, the weakness of the United State's recovery and the euro area's recent relapse are starting to take their toll and, in 2012, for the first time in more than ten years, the Asian giant will grow below 8%. Within this context of economic slowdown, one cause for concern is the real estate sector, in particular the risk of a bubble bursting that would bring the country's activity to an abrupt halt.(1)

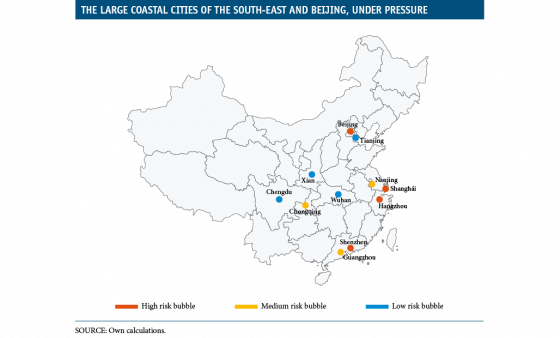

However, has there really been a rise in Chinese house prices that can be classified as a bubble? In spite of the limited amount and reliability of official indicators on the real estate sector, most studies suggest that we cannot speak of a widespread real estate bubble in China but rather of localized bubbles in the cities of Shanghai, Shenzhen and Hangzhou, all on the south-east coast of the country, as well as in the capital, Beijing (see map).

In this respect, and according to data from the Institute of Real Estate Studies of Tsinghua University, prices in 35 of the largest cities grew by around 225% in real terms during the period 2000-2010, equivalent to an average annual rise of 8.5%. In a country whose GDP has grown by 10% annually over the last thirty-five years, 8.5% real growth in house prices does not seem extraordinary. Similarly, during 2011 and the first half of 2012 these prices stopped rising and even fell, picking up again slightly over the last few months. However, this trend hides substantial differences between some large coastal cities, where the increases have been substantial, and other smaller, inland cities with lower growth.

Various factors help to explain why house prices in the large coastal cities have risen so fast: the big increase in household income; urbanization and migration from rural areas to cities; the strong fiscal stimulus and relaxation in credit conditions during the Great Recession of 2008-2009; the role of local governments in selling licences for land and the demand for land by public corporations and, finally, the role played by the low interest rate and lack of alternative investment options in the country.

The large metropolises have seen higher rates of economic growth than the rural areas. Whereas city incomes doubled those of rural areas at the beginning of the 1980s, the difference is now around 3.5. This disparity is even larger in the case of the big coastal cities in the south-east of the country, which have emerged as the motors of growth for the economy as a whole over the last thirty years.

Secondly, the urbanization process that started in 1978, through which more than 300 million people have moved to the cities from rural China, has boosted demand for real estate in these large cities. In the last few years, the coastal cities in country's south-east have become the main destinations for rural immigrants.(2)

Strong fiscal stimuli and the relaxation of credit conditions at the end of 2008 are also very likely to be behind the large increase in prices in 2009, which was more generalized throughout the country. With the aim of combating the effects of the global financial and economic crisis, the Chinese government announced a fiscal stimulus of 586 billion dollars (7% of annual GDP) for the period 2009-2010 and significantly relaxed restrictions to growth in credit, pushing this variable up to extremely high levels, with total credit growing by 32% in 2009, far above the 15% average annual growth during the last five years.

Fourthly, and as is happening in other countries, revenue obtained from licences for urban land is the main source of income for many municipalities, accounting for around 50% of their entire revenue. In the case of the Asian giant, this dependence is related to the limited capacity of local governments to levy taxes, powers that are highly concentrated in the hands of the central government. This situation, in combination with the strong fiscal stimulus of 2009 aimed largely at investment in infrastructures managed by local governments, led to a sharp rise in land prices and, consequently, the price of real estate.

The role of the public sector as a buyer of urban land has also played its part in determining prices. In particular, there is evidence that large state corporations have acquired land at higher than market prices. Some studies have estimated, for example, that public corporations of the Beijing area pay 27% more per square metre of land.(3) Their privileged access to credit through state banks, behaviour that is not always based on purely commercial criteria and personal relations that link managers of public corporations with members of the local government are just some of the explanations provided for these higher bids being offered by such companies.

Lastly, the low real interest rate on deposits, very often in negative figures, and the lack of alternative investments mean that the housing market is practically the only investment option for small savers.

Whether there is a bubble in China or not affects the likelihood of the real estate sector suffering an abrupt halt. But what would be the effect of this halt on the country's economic activity, should it occur?

By way of example, taking into account the fact that residential investment accounts for around 12% of GDP, a slowdown in its real growth rate to, for example, 6% from the figure of 22.5% recorded in 2011, would «directly» reduce GDP growth by 2 percentage points. Moreover, we must also consider the effects on household consumption and the country's total imports. In particular, the fall in imports as a result of a drop in residential investment would adjust the slowdown by 0.5 points (as approximately 20% of this investment is in imported materials). On the other hand, the impact on consumption will mainly depend on how much household wealth would be destroyed by a hypothetical fall in house prices and the relationship between this wealth and consumption. So, as the real estate wealth of households accounts for 150% of GDP and the wealth elasticity of demand is between 1% and 3% (according to different studies), a 10% fall in house prices would result in a reduction of consumption that would deduct between 0.15 and 0.45 points from growth in GDP (0.3 percentage points if we take the average). This would ultimately lead to a slowdown of around 1.8 points in China's growth and therefore a deceleration of about 0.3 points in world growth. According to this scenario, China would record growth of around 6%, a figure that, although it may not sound alarming, would make it difficult to absorb rural labour migrants, aggravating social tensions.

In short, the exorbitant rise in house prices has not been uniform or widespread in China but has been concentrated in a few of the country's large cities, principally Shanghai, Shenzhen, Hangzhou (on the south-east coast) and Beijing. In spite of this, and given the sector's economic weight, its affect on social discontent and the relevance of these large cities in economic, demographic and real estate terms, it's important not to lose sight of the risk entailed by a real estate boom. Recent examples of other countries are a case in point.

(1) This article is based on the "la Caixa" Working Paper 04/2012, «¿Hay burbuja inmobiliaria en China?».

(2) See Chan, Kam Wing, «China, Internal Migration», in Immanuel Ness and Peter Bellwood (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Global Migration, Blackwell Publishing (to be published in 2013).

(3) See Wu, Jing, Joseph Gyourko and Yongheng Deng, «Evaluating conditions in major Chinese housing markets», Regional Science and Urban Economics, volume 42, issue 3, May 2012, pages 531-543.

This box was prepared by Clàudia Canals

International Unit, Research Department, "la Caixa"