As for now, the appreciation of the euro poses no risk for growth

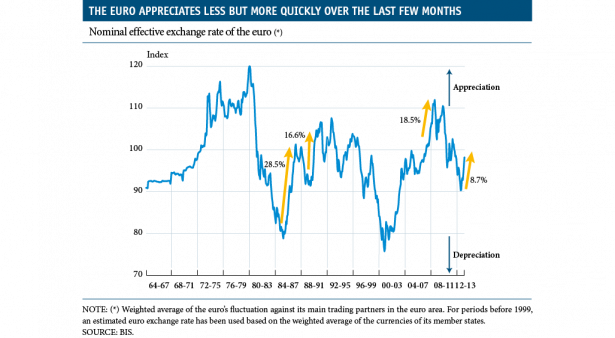

The euro's recent appreciation has brought the foreign exchange market to the forefront of economic debate. The expansionary monetary policies of some of the main central banks pushed up the single currency's nominal effective exchange rate to 8.7% between July 2012 and February 2013.(1) This climb did not stop until the president of the European Central Bank (ECB), Mario Draghi, warned that it will closely monitor money market developments. However, fears of a possible currency war weakening the economic recovery in the euro area have not entirely dissipated.

Such fears seem well-founded: a stronger euro makes exports from the European Monetary Union (EMU) more expensive and, at the same time, makes imports cheaper. Given that the main engine of growth in the last few years has been the foreign sector, this is of the utmost concern. As can be seen in the graph below, the exchange rate has been far from stable over time but what is particularly notable is the speed with which the euro has appreciated over the last year, faster than in other periods. An historical perspective, however, shows us that this movement is not so uncommon. For example, between February 2006 and August 2008, the euro's value increased by 18.5% and between March 1985 and February 1987 by 28.5%.

The economic impact of an upswing in the euro similar to that of the last six months is not too large. According to the ECB's estimates, a permanent 10% rise in the euro's nominal effective exchange rate results in a 0.2 percentage point reduction in gross domestic product (GDP) in the first year, and a 0.6 percentage point reduction in the long term.(2) If we apply this to the euro's appreciation from July 2012 up to February 2013, namely 8.7%, economic activity will have deteriorated by 0.17 percentage points this year. However, the first few weeks of March have seen some correction in the euro's recent appreciation and this shorter duration would reduce the ultimate effect on growth. To achieve a short-term contraction in GDP greater than 0.5 percentage points much sharper and longer-lasting fluctuations would be needed in the exchange rate; for example, an appreciation in the currency similar to the one recorded between 1985 and 1987. The effect, therefore, is not insignificant but neither does it seem enough to jeopardize the recovery process, at least for the time being.

In part, one of the factors that are helping to soften the impact of exchange rate variations on exports is exports' low end price sensitivity to exchange rate movements. This is due, among other factors, to the capacity of exports to absorb part of the currency fluctuations, either by narrowing profit margins or by using financial instruments to hedge against foreign exchange risk. It is estimated that, in the euro area, only half the appreciation of the currency is transferred to the end price of exported goods, a figure very similar to that of Japan and the United Kingdom.(3) In the case of the United States, however, this sensitivity is even lower as only 12% of the currency's appreciation ends up reflected in the end price of exported goods.

Other factors which also play a key role in determining the effect of exchange rate fluctuations on economic growth are: how open the economy is, the import content of its exports and their level of technology. With regard to the first aspect, more open countries are naturally more exposed to exchange rate variations. In this respect, the differences between the various countries in the European Union are very big. At one end of the scale we find the Netherlands, with a level of trade openness, defined as exports and imports as a percentage of GDP, to countries outside the euro area of 81.5% of GDP last year. However, in France and Spain this figure did not reach 25% of GDP. Germany is in the middle, with a 42.0% degree of openness.

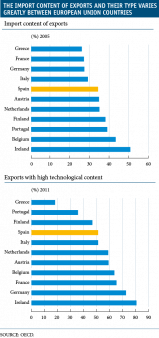

Another factor to take into account is the import content of exports; i.e. the imported products required to generate an exported good. A comparison of the two extreme cases is highly intuitive: a reduction in foreign demand for a country in which everything is produced using domestic goods (zero import content) will have a much greater effect on GDP than in another economy where all the exported goods have been previously imported. In the graph on the left we can see the import content of exports from the main euro area countries. Of note is the fact that, apart from Greece, the four largest countries have the lowest import content of their exports, with figures below 30% in France, Germany and Italy and 34% in Spain. This relationship can be partly explained by the larger size and greater diversification of their economies. On the other hand, Ireland, Belgium and Portugal head the list of countries with a higher import content in their exports.

The last factor to take into account is the technological content of exports. Several studies have noted that demand for exports with a lower technological content is more price sensitive.(4) Those countries specializing in exports of high tech products will therefore be less exposed to exchange rate fluctuations. Both Germany and France stand out in this case since, in addition to having a lower import content for their exports, they are also more specialized in high tech products. At the other extreme we find Greece and Portugal, with an 18% and 36% share of high tech exports respectively.

Looking at Spain's situation, we can see that it is in a comfortable position between these last two cases. Consequently, the impact of the single currency appreciating on economic activity would not be very different from that on the euro area as a whole. Moreover, the Spanish economy's different trade pattern, with a significant share of its exports going to euro area countries, places the appreciation of the nominal effective exchange rate for the Spanish economy at 2.2% between July 2012 and February 2013, so that any impact on growth would be incidental.

In short, in spite of recent fears the relatively limited appreciation of the euro over the last few months does not look like having any significant effect on growth in the euro area or on that of the Spanish economy. But the margin is not infinite, especially now that the export engine is the main driving force for the recovery. It is therefore a good idea for the European Central Bank to monitor its developments very closely.

(1) The euro's nominal effective exchange rate is calculated as the average of its value against the currencies of its main trading partners, adjusted by the volume of exports to these countries.

(2) See Mauro, Rüffer and Bonda, «The changing role of the exchange rate in a globalised economy». ECB Occasional paper series (2008).

(3) See Hamid Faruqee, «Exchange Rate Pass-Through in the Euro Area: The Role of Asymmetric Pricing Behavior», IMF Working Paper (2004).

(4) See Carlos Martínez-Mongay: «Competitiveness and growth in EMU: The role of external sectors in the adjustment of the Spanish economy», European Commission Economic Papers (2009).

This box was prepared by Joan Daniel Pina

European Unit, Research Department, "la Caixa"