A reformist drive is shaking up Mexico

Over the next twenty years, the average annual growth expected for Mexico is slightly above 3%, similar to that of Brazil but far from the 4% predicted for Colombia and Peru (according to the projections of Oxford Economics, a firm specialising in very long-term forecasts). Given that the country is going to flourish in demographic terms, with its population increasing by 20% during these two decades, any significant increase in its growth potential will require an appreciable improvement in productivity. With the aim of improving efficiency in different economic areas and overcoming this prognosis, Mexico is undertaking a series of ambitious reforms, the so-called Pact for Mexico. This agreement, signed at the end of 2012 by the three main political parties in Mexico (PRI, PAN and PND), introduces substantial changes in labour, education, telecommunications, finance, energy and the fiscal area. A challenge of such proportions is unprecedented as, since the disastrous «lost decade» of the 1980s, the country has followed a bumpy road in terms of its reforms (see the article «The economic rise of Mexico: better now than ever» in this Dossier).

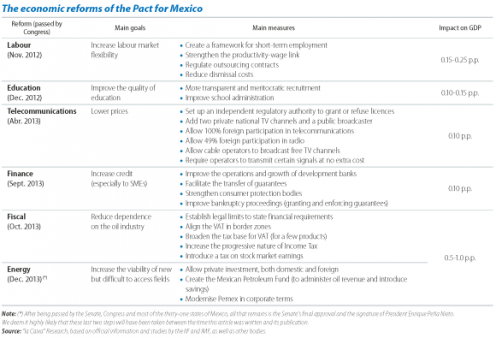

Should they be fully implemented, the economic impact of these six reforms will be considerable. Although there are discrepancies among the bodies estimating the resulting potential increase in GDP, it seems plausible that Mexico will go from its current growth potential of 3%-3.5% to 4%-5%. Also significant is the agreement regarding which reforms will result in most gains in efficiency: the combination of fiscal and energy reforms will contribute between 50%-60% to the increase in growth potential while the rest will be provided, in approximately equal measure, by the other four areas (labour, education, telecommunications and finance).

After months of tough, intense negotiations, all these reforms had been passed by the end of 2013.(1) The first two, labour and education, aim to improve the existing economic incentives in their respective areas so that economic agents behave more efficiently. Specifically, the former attempts to strengthen the link between productivity and wages, while introducing measures to make hiring and contracts more flexible. Educational reform focuses on improving the quality of education by means of a more efficient teacher provision system. This involves a shift from a system in which, de facto, people could inherit or buy certain teaching posts to another based on merit.

For its part, the telecommunications reform aims to replicate the process carried out in other countries, consisting of opening up the industry to direct foreign investment and creating a regulatory body with the authority to grant licences in the sector. The financial reform, however, has a more specific aim, namely to boost and lower the cost of credit, particularly for financing projects by small and medium-sized firms. This reform has strengthened the role of development banks (in particular by enlarging the system of loan guarantees) at the same time as adopting, as legally binding, the requirements of Basel III in the Mexican case and reinforcing different institutional aspects (such as consumer protection, the powers of the bank regulator and bankruptcy proceedings by creating specific courts).(2)

In the last quarter of 2013, the last two reforms (fiscal and energy) completed their parliamentary process, precisely those with the greatest economic impact. The fiscal reform, whose main aim is to reduce Mexico's tax dependence on oil revenue (approximately one third of public revenue comes from oil-related activities), combines elements of fiscal policy in a broad sense with more specific tax-related aspects. On top of the existing fiscal limit, which establishes that the government must achieve a fiscal balance, additional restrictions have now been introduced that help to meet the public debt targets set. With regard to strictly tax-related aspects, the reform aims to enlarge non-oil revenue via a battery of measures that include (limited) changes to the taxable base for VAT, an increase in the VAT rate for firms operating in crossborder zones and the creation of a new tax on stock market earnings.

The energy reform, which is in the final stage of its approval, aims to increase oil extraction as, since 2003, production has fallen from 3.4 million barrels a day to the current figure of 2.5 million. Without any clear improvement in extraction technology, Mexico is unlikely to be able to take advantage of its oil reserves that are difficult to access, such as the so-called «deepwater» sites, or to exploit mature oilfields. Changes are also proposed in the management of Pemex, in strictly organisational and corporate terms. In response to these requirements, three articles of Mexico's Constitution will be revised to allow privately owned firms to enter the energy sector by means of a wide range of instruments. Pemex will also be forced to become more competitive within a period of two years.

In order to facilitate the corporate changes required to achieve this goal, the petroleum trade union will give up its place on the Pemex board of directors, where it had represented one third of the members for more than seventy years. To tackle its presumably more competitive private rivals, Pemex will be guaranteed priority in choosing sites. Lastly, a new Mexican Petroleum Fund for Stabilisation and Development will be set up, which will be used to finance different items of public spending such as science and technology projects and state pensions. This is a complex reform at a technical level but it is even more difficult in terms of social acceptance, as it could come up against one of the fundamental elements of Mexico's collective imaginary, namely the state ownership of oil (embodied in the nationalisation of crude carried out by one of Mexico's most popular presidents, Lázaro Cárdenas, in 1938). The solution reached means that Mexico will continue to ultimately own its oil.

Although it is still too soon to fully assess the outcome of this package of reforms, it should be acknowledged that, although the adoption of structural reforms in waves is not exceptional, the approval in approximately one year of six reforms with the far-reaching effects of those just mentioned is not an everyday occurrence in a market economy. It therefore comes as no surprise that some of these reforms have turned out to be less substantial than expected, as in the case of the fiscal reform. But neither should we forget that other reforms, such as the most controversial one related to energy, have fully accomplished their most ambitious goals. For example, while the initial proposal was merely to allow private firms to operate on a limited basis, the project finally adopted has extensively broadened the instruments available. The immediate challenge is to ensure that the laws passed, which are essentially framework acts, are implemented in detail without losing their essence. Then, and only then, will Mexico be in a position to speed up its rate of growth towards levels befitting the country's potential.

Àlex Ruiz and Clàudia Canals

International Unit, Research Department, "la Caixa"

(1) Strictly speaking, the energy reform is pending ratification by most of Mexico's states although it has been passed at a federal level. As mentioned in the table enclose in this Dossier, the approval process is almost complete.

(2) For a complementary assessment of the banking reform, see the article in the Dossier of this Monthly Report entitled «Mexican banks: solvent and with room to grow».