Brexit: strong impact on the United Kingdom, more diffused in the EU

The decision to leave the EU by the United Kingdom brings with it important political consequences. The Brexit vote won the referendum on 23 June by a narrow margin (52% vs. 48%). Meanwhile the country has begun to suffer from considerable political crisis which is causing great uncertainty. One initial political repercussion has been the resignation of the British Prime Minister, David Cameron. This will come into effect in October when a new leader of the Conservative party will be nominated, who will have to lead negotiations with the EU. Scotland, which voted overwhelmingly to remain in the EU, could rethink its relationship with the rest of the country.

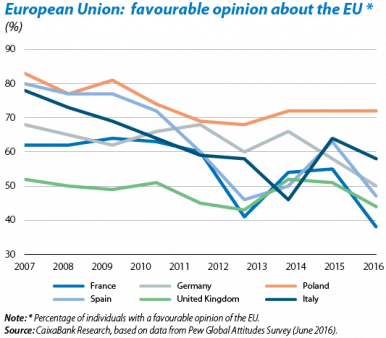

EU negotiations, a key factor over the coming months. The EU has communicated its desire to quickly negotiate the terms of the UK's exit so as not to prolong uncertainty and attempt to keep the country as a close partner. In these negotiations the EU will have to find some middle ground between a tough stance, which avoids a knock-on effect and further referendums, and an accommodative stance that minimises the impact on the real economy. The member states are also facing a difficult political calendar (referendum on Italian constitutional reform in October, legislative elections in Germany and France in 2017, etc.) and an increase in the dissatisfaction of European citizens with the EU project, with the added factor of advances being made by Eurosceptic and populist parties. Over a longer timeframe, the United Kingdom's exit might act as a catalyst to reinforce commitment to the European project and the euro in the rest of the countries. One possibility would be to accentuate the different speeds of integration in Europe, with greater intensity in the euro area. However, the lack of strong leadership in the EU and growing Euroscepticism could derail this scenario of greater European integration.

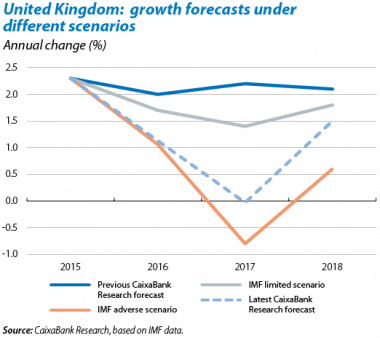

Appreciable economic impact of the Brexit for the United Kingdom in the short term. The United Kingdom is likely to imminently fall into a recession due to the high level of uncertainty which will act as a brake on decisions to invest, hire and consume. Its size and depth will depend on how this uncertainty develops. Should it increase, there will be more pressure to achieve an exit that does not entail a radical break with the current situation. We expect the economy to start to normalise as negotiations begin with the EU, probably at the end of 2016 or beginning of 2017. For the moment, the Bank of England has injected additional liquidity and could soon cut interest rates. In the long term, the cost of the Brexit will largely depend on the nature of the UK's new relationship with the EU, in particular agreements on trade and the circulation of people, and also with other countries (for more details see the Focus «Brexit: a gamble with more costs than benefits» in MR05/2016). Estimates of the cost in terms of GDP by various organisations fluctuate between –1% and –10%.

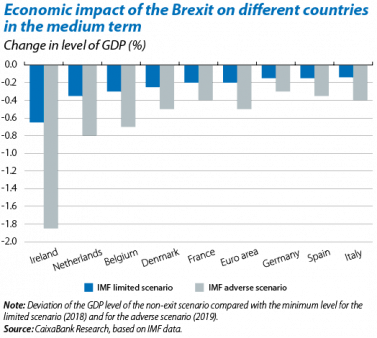

The economic consequences for the rest of the member states should be moderate. The Brexit will tend to have a direct impact (via the commercial channel) on the rest of the EU countries due to the recession in the UK and, indirectly, to an upswing in uncertainty. However, the overall effect should be modest, equivalent to few tenths of a percentage point for most countries. Repercussions in some economies such as Ireland and the Netherlands will be greater due to their strong links with the United Kingdom. The macroeconomic deterioration could be worse if political cohesion wanes in the EU, if economic policies (monetary, fiscal, etc.) lose their effectiveness or if other external risks materialise, both geopolitical and economic.

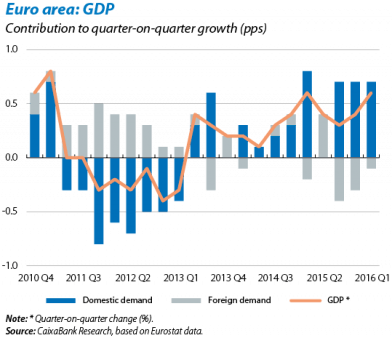

The economy of the euro area, in a condition to withstand the shock. The context in which this economic shock of the Brexit is occurring is nevertheless relatively positive. In 2016 Q1 the euro area added its thirteenth consecutive quarter with GDP growth (and has now recovered the real GDP level it had before the crisis in 2008). Specifically, in Q1 the quarter-on-quarter increase in GDP was 0.6%, slightly higher than the figure of 0.4% posted in 2015 Q4. In addition to its favourable rate of activity, we should also note the balanced composition of this growth. Domestic demand continued to be the major contributor to the change in GDP (+0.7 pps), in particular thanks to private consumption (+0.3 pps), whose contribution increased. Public consumption and investment contributed, respectively, with +0.1 pps and +0.2 pps and, together with private consumption, these are likely to be the pillars for growth in the euro area over the coming months. Given the inertia that tends to be shown by domestic demand, its strength comes from certain margin of autonomy of the cycle of countries in the euro area in relation to the more direct economic channels through which the Brexit effect will be transmitted. Exports reduced their negative contribution to growth in Q1 (–0.1 pps), especially because of the lower growth in imports compared with exports.

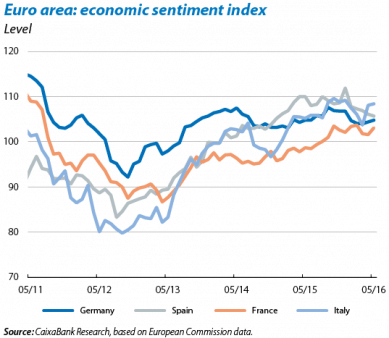

Activity increases in Q2. This good economic performance is not limited to the first three months of the year. In May, the euro area's economic sentiment index reached its highest level in the last four months (104.5 points). Of note is the rise in France (+1.5 points) and, to a lesser extent, in Germany (+0.4 points) and Italy (+0.3 points). These good figures more than offset the slight drop posted by Spain (–0.4 points). Other indicators, such as industrial production and the PMI indices, also point to the progress made by activity being similar in Q2 to that recorded in Q1.

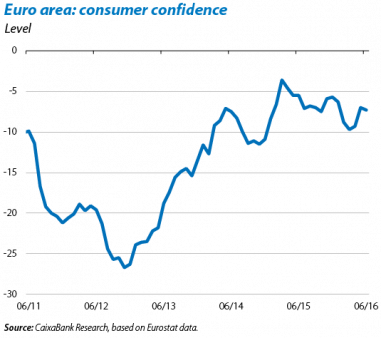

Consumption keeps up a notable pace. Consumption indicators suggest that household spending grew a little less in Q2 than in the previous quarter but is still within a reasonably positive zone. The euro area's consumer confidence index reached –7.3 points in June, recovering almost all the ground lost in Q1. The data available point to this improvement in consumption reaching expenditure on durables, in particular car purchases, a trend undoubtedly related to the progressive normalisation of credit. In addition to private consumption, investment is another support for appreciable growth, as witnessed by the industrial production of capital goods which approximates the trend in gross fixed capital formation.

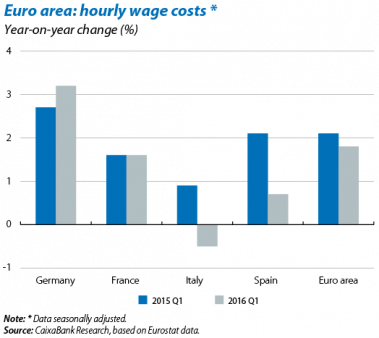

A moderate but continued improvement in the labour market. This expansion by consumption is largely supported by the continued expansion in the labour market. In 2016 Q1 the rate of job creation in the euro area was equivalent to the rate in the second half of 2015 (0.3% quarter-on-quarter) while unemployment stood at 10.2% of the labour force in April, its lowest figure since early in 2011. With regard to wage costs, in 2016 Q1 the year-on-year growth was 1.8%. Although this shows some acceleration compared with year-on-year figure of 1.5% for Q3 and 2015 Q4, the rate of growth is lower than the one recorded a year earlier when was 2.1% and, in any case, it is still in line with the economic expansion taking place in the euro area. It should be noted, however, that the trend in wage costs is notably different depending on the country in question. While wages grew by 3.2% year-on-year in Q1 in Germany, in Spain the rise was more moderate (0.7%). Nonetheless the most contained situation is in Italy, a country that posted a 0.5% drop in its wage costs.

Inflation returns to positive terrain in June. The harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP) grew by 0.1% year-on-year in June, its first positive rate since last January. In May the HICP had fallen by 0.1%. This growth in the general level of prices was especially due to the smaller drop in the energy component whereas core inflation remained stable in June at 0.8% year-on-year. Over the coming months, and should the CaixaBank Research scenario come about, inflation will gradually reflect the rise in oil prices, with the energy component notably reducing its negative contribution as from August.

Italy has a high risk profile. The Brexit has increased the perceived risk of peripheral economies. One of the states that fully embody investors' concerns is Italy. This country has a threefold source of risk. First of all, the economic recovery it has been enjoying since the crisis has been much more moderate than for the euro area as a whole, a situation that has yet to correct itself (Italian growth was 0.3% quarter-on-quarter in Q1 compared with 0.6% for the euro area). A second source of risk results from doubts regarding the solvency of Italy's banks. In spite of having set up a private fund which should accumulate a significant part of doubtful bank assets, there are still questions regarding whether it will be able to fulfil its function, questions which have been increased by the fact that the government and the Bank of Italy are considering an injection of liquidity of around 40 billion euros. The third source of risk is political. Next October there will be a referendum to accept the Senate's change in role, a modification which will help policymaking. The results of June's municipal elections suggest that support for the incumbent party is waning, which adds uncertainty regarding the capacity for effective reform which the Italian electorate may be in a condition to take on.