For some years now people have been warning about the risk of the euro area becoming «Japanised», a term with clearly negative connotations. In fact, numerous observers perceive Japan's economic development over the last few decades as a series of misfortunes whose cause dates back to the second half of the 1980s with the formation of a huge credit, real estate and stock market bubble. The inevitable bursting of this bubble led to problems which lasted throughout a tortuous hangover plagued with zombie banks, rocketing public debt, persistent deflation and meagre growth in GDP. However, others point to variables in which Japan has performed at least satisfactorily: per capita income that has continued to rise and is among the highest in the world, an unemployment rate that has remained very low, a relatively low inequality rate in income distribution as well as enviable rankings in terms of international competitiveness. Two questions spring immediately to mind: to what do we owe this disparity in perceptions and to what extent does Japan represent a compendium of what the euro area must avoid?

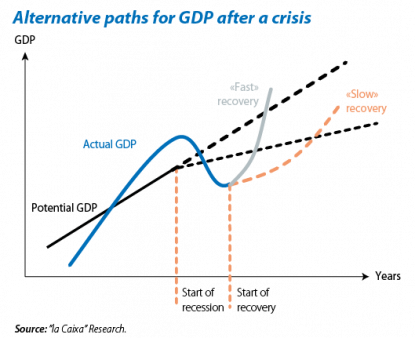

Such warnings of Japanisation are directed at economic policymakers, claiming that the Asian country made several far-reaching mistakes. The strongest complaints refer to anti-cyclical policies whose aim is for the economy to achieve and sustain full production capacity: namely monetary, fiscal and also financial sector policies. But there has also been criticism of policies regarding structural reforms designed to increase the country's potential production capacity. The next two articles in this Dossier examine these areas in detail to cast some light on the euro area's case. We should make two provisos regarding this segmentation of the analysis, however. One relates to form: the decision to ascribe a policy to one area or another seems to be somewhat arbitrary. In particular, the policy related to the financial sector is clearly demand-oriented insofar as it is crucial for monetary measures to be passed on to the real economy. But it also exercises notable influence on supply and potential growth insofar as a healthy financial system is key to mobilising resources precisely towards more productive destinations. The second proviso is more fundamental in nature: the way in which these policies interact is complex; sometimes reinforcing and sometimes counteracting each other before achieving their effects on the different variables in question. Judging each one in isolation could be misleading or lead to an incomplete conclusion, especially when analysed over the short term. That is why it is useful to frame our examination of individual policies within an assessment of the policy mix, taking into account the results achieved in terms of the ultimate proposal to improve and sustain the economic well-being of citizens. To this end, the first graph illustrates the possible alternative paths that could be taken by GDP after the economy receives a shock and a crisis ensues. The spectre of Japanisation refers to the route identified as a «slow recovery». Japanese policy is often criticised in comparison with that of other countries, in particular the United States, which would have been more suitable to position itself along the route identified as a «fast recovery».

Japan's economy was hit hard by several shocks in the 1990s. The first, at the very start of the decade, when the aforementioned bubble burst; the second in 1997 when some banks went bust that had been suffering since the initial shock and with the emergence of the financial crisis in several countries in South East Asia. Similar shocks in the US occurred a few years later: the bursting of the dotcom stock market bubble in 2000 and particularly the real estate bubble in 2007, sowing the seed for the dreadful post-Lehman financial crisis. The anti-cyclical policies implemented in these two countries appear to take opposing stances. In the area of monetary policy, the Federal Reserve reacted very aggressively, quickly cutting official interest rates and deploying a large-scale quantitative easing programme while the Bank of Japan was much more timid in the 1990s and 2000s, taking its time to cut interest rates and hardly using quantitative easing at all. In the area of fiscal policy, the US adopted a strategy of stimuli concentrated in time and selective in content in order to revive critical economic engines. In Japan, the crisis in the 1990s made the public deficit rocket, which has remained high. A large amount of debt has been built up but there are serious doubts regarding its capacity to stimulate demand and also how efficiently this has been spent, often on public works that have not been very productive. But perhaps the biggest discrepancy occurs in the area of banking sector policy. Here the US also opted to act decisively, forcing the prompt recapitalisation of banks in difficulty and openly reserving public money for this. Japan followed a different route, delaying both the acknowledgement of debt and bank recapitalisation. This led to the problem of zombie banks which frequently attempted to provide precarious support to equally moribund companies. According to the widely accepted version of events, such timid, inconsistent anti-cyclical policies by Japan for more than 20 years merely prolonged the problems caused by insufficient aggregate demand, making the situation chronic as well as aggravating the accumulation of public debt. The failure to revive demand, this version continues, has had serious repercussions in the form of deflationary pressures and a reduction in potential GDP given the emergence of so-called hysteresis effects (cancelled investment in production, discouraged workers leaving the labour market or losing skills because they are unemployed for too long, etc.). Some even claim this was further aggravated by the lack of structural reforms substantial enough to transform a far too paternalistic labour relation system and regulations that encouraged rigidity in the goods and services markets. In this case the benchmark, be it explicit or implicit, is also the US with its free, flexible market model.

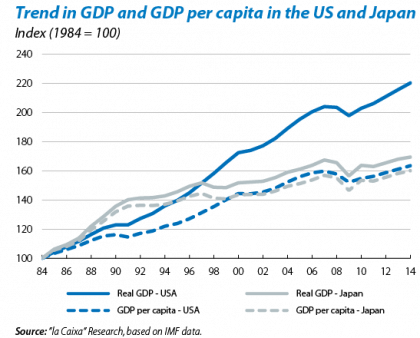

Criticism of Japanese policies is based on the macroeconomic results achieved. A preliminary analysis confirms such criticism: over the last three decades, Japan's cumulative growth in GDP has been slightly lower than the US at the same time as recording persistent deflation. The diagnosis is very different, however, when we look at growth in GDP per capita, a more appropriate variable, in principle, to measure the economic progress of citizens. In this respect the Japanese figure is much closer to that of the US. As is well-known, Japan was the country that first, and most quickly, entered what has been called «demographic transition» (the ageing and slowdown of the population). What is less widely known is that the negative impact of this development on total GDP (direct insofar as the labour force has been shrinking since the early 1990s) has not stopped the trend in GDP per capita which, at least so far, has been reasonably satisfactory. It is also possible, although there are many conceptual and empirical doubts to the effect, that demographics have influenced the country's situation of persistent but gentle deflation (the Japanese CPI fell by 4% overall between 1998 and 2012, a modest figure compared with the slump of 25% in the US between 1929 and 1933).

The demographic factor seems to have taken the sting out of the criticism but it would be a mistake to become complacent. On the one hand, its trend is not completely exogenous to the economic trend itself, especially over long periods; for example, hysteresis and supply policies, as well as the birth rate or immigration, also have an impact. On the other hand, although Japan's demographic patterns must be seen as a result of individual and collective preferences that are freely exercised, the resulting long-term effects are no less important. Two such effects are particularly worrying from now on: the increase in the burden of public debt on future generations with fewer members and the possible loss of innovative drive and of the willingness to take business risks.

Given the above, it can be concluded that there are several reasons for diverging opinions regarding the Japanese experience mentioned at the beginning. The first is the «elephant in the room» phenomenon; i.e. an obvious factor (demographics) being omitted from the discussion by some, perhaps because it spoils certain analyses and conclusions. The second is less evident and more controversial: different views regarding the best economic and social model and, by extension, the right economic policies. Related to this, a third aspect concerns how the circumstances surrounding the decisions taken at each historical moment are evaluated, in particular the institutional framework and international environment. These last two have been important factors in the shift in economic policy introduced in 2013 by the Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, now actually coming closer to the US formula. In some way, such a shift might acknowledge that previous economic policy had been far from appropriate. As explained in the next two articles in this Dossier, over the last few years Japan has made some mistakes that the euro area would be wise to avoid but the global results reviewed here indicate that it cannot be seen as a total disaster by any stretch of the imagination.

Avelino Hernández

Financial Markets Unit, Strategic Planning and Research Department, CaixaBank