Millennials: a new notion of work?

Millennials and the effects of the crisis

The economic situation was not always in their favour when Millennials first joined the job market. And it was particularly adverse for Spanish Millennials born after 1987 who, with a deep crisis in the making, saw many of their job expectations frustrated or, at the very least, had to put them on the back burner until better times.

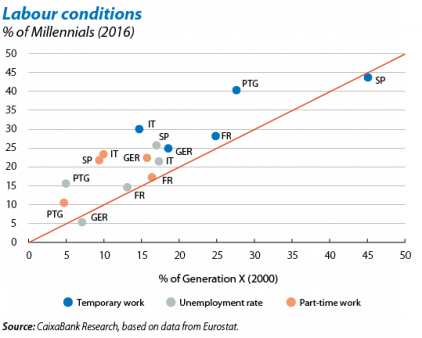

Even now, finding a job is no easy task. The unemployment rate for Spanish Millennials is 26% (in 2016), much higher than for the previous generation (Generation X) when they were the same age as the Millennials now (17% in 2000).1 This is also the case in other European countries such as Portugal and Italy. But such differences between generations are not limited to the difficulty of finding employment. Even once European Millennials have secured a job, their employment conditions, in terms of temporary and part-time contracts, have also tended to be worse than for the previous generation, especially in Spain, Italy and Portugal (see the first chart).

Several studies agree that joining the job market during an economic recession, as was the case for late Millennials, has a negative effect on employment and wages that can take years to disappear.2 Although the negative impact on the probability of finding employment tends to dissipate after three years, the effect on wages can last ten. Studies suggest that, in the case of the UK, the disadvantage of having been unemployed at the beginning of one’s working life can reduce the wages received 20 years later by almost 8%.3 Moreover, such consequences are not limited to the most vulnerable groups but also affect university graduates, doctorates and even MBAs.4 On the other hand, cohorts that join the job market during a boom tend to be promoted more quickly and reach higher positions.5

What makes Millennials different at work?

In spite of the adverse economic conditions they may have encountered, Millennials are a highly trained generation that can add value to the labour market. Although most generations appreciate similar aspects of their employment, such as the work-life balance and a competitive wage, there are some features which Millennials tend to consider more important than previous generations. So what kind of company policies are more likely to attract (or retain) Millennials? Most reports highlight the following aspects:6 i) Opportunities to work with the latest technology and receive training, ii) Close relationship with superiors and regular feedback, and iii) A collaborative and flexible atmosphere.

Another area of speculation regarding how Millennials work is their alleged lack of commitment. However, are Millennials truly less committed to work than other generations?

For the case of the US, some studies suggest that Millennials change their job more often, warning of the costs incurred for the economy. However, if we take into account the overall increase in mobility, Millennials do not appear to be any less stable than other generations.7

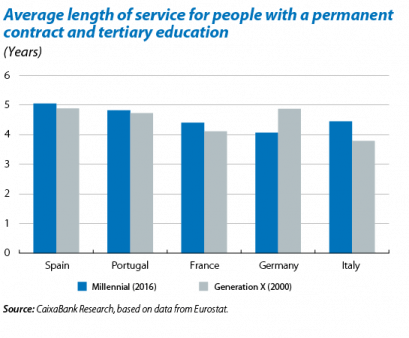

In fact, in European countries the data suggest that the average length of time spent by Millennials in a job is relatively similar to the previous generation, especially when we compare Millennials and Generation X members with similar employment and educational conditions (see the second chart). So these data do not point to any less commitment on the part of Millennials.

There are other, softer indicators which can also provide us with clues about whether they are less committed to work. For instance, whether Millennials tend to look for another job while they are still employed. Here the results differ across countries. In Spain and Portugal, more employed Millennials state that they are looking for work than their peers from Generation X, which could indicate a change compared with the previous generation. However, this is not the case of French or German Millennials, who behave in the same way as the previous generation.

In summary, the data seem to suggest that the main differences in employment terms between Millennials and other generations are not so much down to individual preferences but to a worse situation for this generation in the labour market. As we mentioned at the beginning, joining the job market during a recession leaves lasting scars in terms of employment and wages which, in turn, affect how Millennials live.

How do Millennials live?

A lack of job security for young people, in combination with their parents’ jobs benefitting from greater protection, has led Millennials to delay the age at which they leave home,8 this currently being 29 in Spain.9 However, these consequences do not only influence when Millennials become independent but also how this emancipation occurs. A shift towards unemployment and modest wages creates difficulties in affording a home. It may be difficult to get a mortgage when employment conditions are unstable or perhaps Millennials cannot afford to buy a property. In fact, Millennials who have bought a home devote 19% of their income to housing-related payments, 0.7 pp more than Generation X at the same age. As a result, Millennials are more likely to rent (55% of young people aged 25 to 29 who have left home rent their accommodation), as well as to take different financial decisions, which are discussed in the next article.

All the evidence therefore seems to suggest that the differences in the labour market between Millennials and previous generations are mainly caused by the impact of the economic crisis. We must not forget that Millennials are one of the generations hardest hit by the crisis and, given that the repercussions will not disappear quickly, their economic performance might depend on the support they receive from society and especially from other generations.

Anna Campos

CaixaBank Research

1. Millennials are defined as those born between 1981 and 1996, and Generation X as those born between 1965 and 1980.

2. See Kahn, L. B. (2010), «The long-term labor market consequences of graduating from college in a bad economy», Labour Economics, 17(2): 303-316.

3. See the European Commission (2014), «Scarring effects of the crisis» and Greeg, P. and Tominey, E. (2005), «The wage scar from male youth unemployment», Labour Economics vol. 12(4): 487-509.

4. See Oreopoulos, P., Von Wachter, T. and Heisz, A. (2012), «The Sort- and Long-Term Career Effects of Graduating in a Recession», American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 4(1):1-29.

5. See Kwon, I., Milgrom, E. M. and Hwang, S. (2010), «Cohort Effects in Promotions and Wages: Evidence from Sweden and the United States», The Journal of Human Resources, 45(3):772-808.

6. See Human Resources Professionals Association (2016), «HR & Millennials: Insights into Your New Human Capital», HRPA Millennials Report.

7. See Adkins, A. (2016), «Millennials: The Job-Hopping Generation», Gallup Business Journal.

8. Becker, S. et al. (2004), «Job insecurity and children’s emancipation», CEMFI Working Paper no. 0404.

9. Eurostat data for 2015.