The world economy in 2026: resilience, transition or disruption?

As we approach 2026, the global economy is once again demonstrating greater-than-expected resilience to uncertainty and geopolitical noise. However, growth and welfare will depend on how the division between economic blocs, the rise of artificial intelligence and fiscal challenges are managed, in a context of transition and increasing complexity.

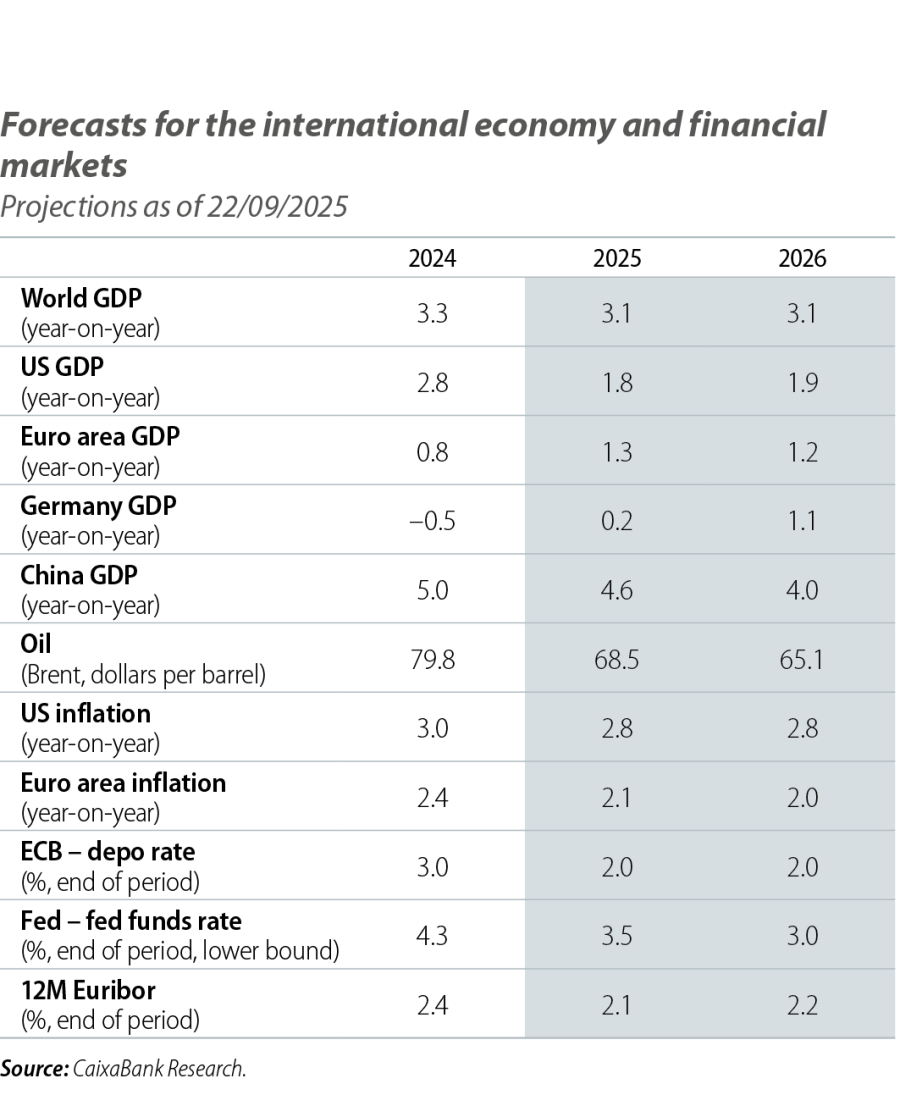

The year 2025 will end with the feeling that the impacts on growth of the various supply shocks and the heightened uncertainty have been limited and far lower than expected following the noise generated during Donald Trump’s first few weeks in office. The global economy continues to show significant resilience and the business cycle is maintaining a cruising speed of around 3%, although the disparities in growth between Europe (1.3%), the US (1.8%) and Asia (4.5%) persist. The list of factors that may explain this strength in economic activity include a milder-than-expected impact of the tariff hikes now that an all-out trade war has been avoided and the flexibility of private agents in anticipating and adapting to the noise of the new economic environment, in addition to the existence of favourable financial conditions.

In fact, we have the same feeling at this time of autumn as we did in 2023 and 2024, when the reality at the end of the year was much better than the baseline forecast scenarios drawn up at the beginning of the year had predicted. There are several factors behind this steady improvement in the economic outlook, including an underestimation of economic agents’ ability to deal with uncertainty and make decisions in times of instability or, simply, the fact that forecasting exercises are complicated in times of high uncertainty. However, in addition to all of the above, the resilience that the business cycle has demonstrated since the end of the pandemic appears to be a reflection of some of the benefits of an old international order that is in the midst of a transformation. This is an economic and political framework (Pax Americana) in which the US has assured the balance of an open world economy by offering essential public goods (defence, security, payment systems, etc.), open markets for trade and a stable currency, in addition to becoming a lender of last resort in times of need (via the IMF).

This environment, therefore, has offered benefits in terms of economic stability, growth, innovation and the optimisation of competitive advantages, but it is now threatened by the emergence of a new global leader (China) which is seeking to establish new alliances and strategic dependencies in the Eurasian continent, as well as in Africa and Latin America.1 At the same time, the old hegemonic power is seeking to rebalance the playing field by charging more explicitly for the services rendered (tariffs, arms spending, direct investment targets, etc.), amid a radical realignment of its foreign policy in this new reality. This realignment process is generating some paradoxes, such as the fact that the theoretical provider of stability and protection is currently one of the main hotbeds of uncertainty and that traditional US allies (Europe, Japan, Canada, South Korea, etc.) could be the most impacted by the changes in the rules of the game.2

- 1

See «The Belt and Road Initiative: a double-edged sword?» in this same Monthly Report.

- 2

See Adam S. Posen (2025). «The New Economic Geography. Who profits in a Post-American World?». Foreign Affairs, Volume 104 no. 5.

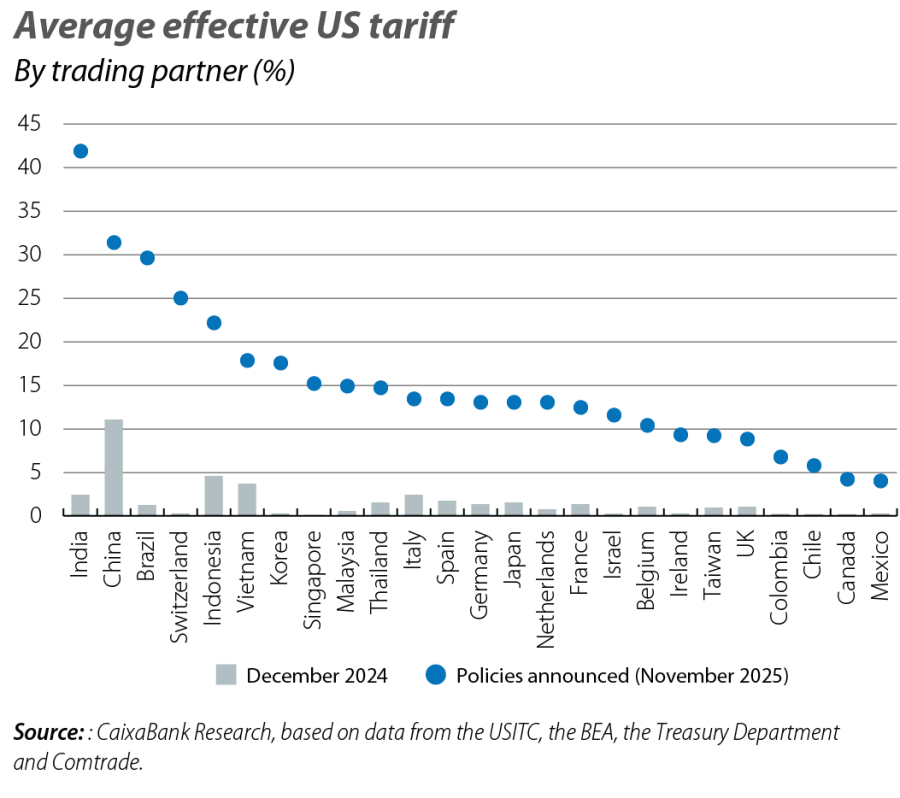

Therefore, geo-economics will continue to play a key role in 2026, as trade and finance appear to have become instruments at the service of political objectives, further complicating any forecasting exercise. The question is whether the current trend towards a more fragmented world will accelerate or, now that the average US tariff has stabilised at around 14,5%-16% (2.5% prior to Trump’s mandate), the strengthening of trade links between the EU, ASEAN, Canada or Australia could partly offset the effects of the US’ reduced openness. In any event, in the short term, the effects on growth and inflation of the new tariff framework will continue to materialise while the shape of the new trade relationship between the US and China is being finalised, and this will be defined by the balance between the two sectors in which there is mutual dependence: rare earths and microchips.

Next year, therefore, we will see a continuation of the reordering of the globalisation process in which the international economy has been immersed since the pandemic. When we eventually emerge from this process, the new balance – characterised by more division between economic blocs – will result in losses in potential growth and well-being which could potentially be offset by the innovation process linked to artificial intelligence (AI). This innovation process has accelerated significantly of late, as demonstrated by US GDP growth in the first half of the year (90% of which is explained by investments made in hardware, software, data centres, etc.).3 The big tech firms alone plan to invest nearly 3 trillion dollars in AI-related items by 2030, representing almost 10% of GDP. The positive short-term boost to activity is assured and could help to offset the first signs of weakening in the US labour market, but the key question is whether this wave of investment will result in greater profits in the medium term. This question is particularly relevant bearing in mind that more leveraged and circular financing structures are beginning to be identified, with cross-holdings between companies in the same sector along the value chain, as this could increase the risks if the returns end up being lower than expected. Moreover, these interdependencies could act as a brake on the creative destruction process, blocking or delaying the entry of new competitors.4

In short, the big question is whether, in the medium term, AI can offset the negative impact of demographics and economic fragmentation on potential growth, via the accumulation of capital and total factor productivity. If successful, this will likely lead to a greater presence of capital in production and a lower proportion for labour, potentially posing an additional obstacle to fiscal consolidation policies, given that it is more difficult to tax capital – because it is more mobile – than labour incomes. Moreover, this is without taking into account that structural changes of this scope tend to require a compensation mechanism to support the losers of this change process in the transition to the new reality, whether they are companies or workers. All this is taking place in a context in which the absence of fiscal space5 in many OECD countries is one of the biggest risks in the scenario,6 especially given the need to simultaneously tackle a variety of challenges such as the energy transition, the new defence spending needs and the effects of population ageing.7

While the medium-term fiscal outlook for the US is not very buoyant – given the IMF’s recent estimate that public debt could rise to 143% of GDP by 2030, while the deficit will not fall below 7% in the whole period – in the short term the focus will be on Europe, with France in the eye of the storm. Fiscal imbalance plus political instability is a recipe that is difficult to digest, especially in a country where tax revenues exceed 50% of GDP yet, despite this, the primary deficit lies above 3%. The diagnosis of the markets is clear: France’s fiscal situation shares more in common with Italy's than with that of Spain or Portugal, and this has already translated into a reordering of Europe’s country-risk, as reflected in the risk premiums and the changes made by the ratings agencies.8 At the limit, the greatest threat is that the mechanisms designed in the past decade to tackle spikes in the risk of fragmentation in Europe (ESM, UNWTO and IPT) could end up being put to the test.

In short, in 2026 the economy will continue to be exposed to the combination of new underlying trends (restrictions on trade and migration movements, AI boom, etc.) and short-term challenges (limited fiscal space, high valuations in financial markets, etc.). This will be a year in which the ability to question the assumptions behind economic projections will once again be decisive, as will be a flexible approach to decision-making. Moreover, the resilience of the business cycle will once again be tested, as we find ourselves between a world that has not quite died yet (globalisation, multilateralism, liberal democracies) and another that has not quite been born. The risk lies in underestimating the changes at hand and believing that we will soon return to the previous status quo, which makes it pertinent to recall the words of Joseph de Maistre: «We had the French Revolution; we were quite pleased with it. It was not an event: it was an epoch.»

- 3

For an in-depth analysis of the outlook for the US economy, see the article «US 2026 outlook: resilience with frailties» in this same Monthly Report.

- 4

See P. Aghion, C. Antonin and S. Bunel (2021). «El poder de la destrucción creativa». Editorial Deusto.

- 5

According to the IMF, global public debt could reach 100% by 2029.

- 6

For further details in the case of Europe, see the article «Europe’s medium-term fiscal dilemma» in this same Monthly Report.

- 7

The IMF estimates that all these challenges could exert pressures on public spending in Europe equivalent to around 6 pps of GDP by 2050.

- 8

It should also be noted that the biggest fiscal shift in the euro area is occurring precisely in the country that has the greatest budgetary margin (Germany), and this is driven by an increase in investment in infrastructure and defence which should kick off in 2026, resulting in a projected jump in public debt of around 15 points between 2024 and 2028 and a structural deficit that is expected to rise to 4% of potential GDP in 2026.