The causes of the departure from employment

We analyse the changes that have occurred in the flow of departures from the Spanish labour market in recent years, and the effect of the entry into force of the latest labour reform.

As we already discussed in a previous Focus,1 employment stability in Spain has improved in recent years, as reflected in the sharp decline in the temporary employment rate and in the reduced flow of entries and departures in the labour market. Although turnover has increased in all types of contracts, the aggregate turnover rate (the sum of Social Security registrations and de-registrations as a percentage of the total number of workers registered under the General Scheme) has reduced due to a composition effect, given that permanent contracts, which tend to have a lower turnover, have increased as a share of the total. In this article we take a more detailed look at one of the determining factors of turnover, namely, departures from the labour market, and we analyse the changes they have undergone, having been significantly affected by the entry into force of the latest labour reform approved in December 2021.

There are several factors that influence outflows of workers from employment. Among others, they include: (i) the digital transformation, which is causing changes in the demand for certain professions and skills; (ii) temporary employment and the outsourcing of services, which contribute to the instability of employment; (iii) crises, recessions or unexpected events such as the pandemic, which lead to job destruction, and (iv) population ageing, given that the empirical evidence shows that labour mobility decreases as workers’ age increases.2

In view of the data provided by the Social Security Treasury, the main cause of affiliate de-registrations (see first chart) remains the termination of temporary contracts. That said, this type of termination of employment has reduced considerably, in line with the fewer number of temporary contracts being signed as a result of the labour reform. In this regard, whereas in 2014-2019 two in every three departures (almost 686,000 per year on average) occurred for this reason, in 2025 (using annualised data to April) that figure has fallen by over 30% to below 477,000, representing 42.5% of the total.

- 1

See the Focus «Employment stability improves in Spain», in the MR02/2025.

- 2

See Bank of Spain (2024). «The impact of population ageing on Spanish labour market flows», Economic Bulletin, 2024/Q3.

On the other hand, there has been an increase in the number of departures as a result of workers becoming inactive under discontinuous fixed contracts,3 a form of contract that has gained prominence with the labour reform. This type of outflow has gone from explaining fewer than 36,000 departures per year on average in the period 2014-2019, representing just 3.5% of the total, to over 237,000 in the trailing 12 months to April, or 21.2%, thus becoming the second biggest cause of de-registrations.

However, what is most striking is the sharp increase in de-registrations due to two other causes: voluntary departures and those not having passed the probation period. Voluntary departures or resignations have almost doubled in the period analysed, exceeding 141,000, or 12.6% of the total, which is 5 points more than prior to the pandemic. That said, they still lie well below the level found in the US, where they are the leading cause of employment termination. This could be related to the recovery of activity and therefore job creation: workers have more incentives to leave their jobs if the chances of finding better working conditions elsewhere are high. Within this type of departure, we can see a significant change in the composition (see second chart): before the pandemic, most of the workers who resigned (63.0% on average in 2014-2019) were temporary (usually with more precarious jobs); in contrast, in 2025 (annualised data to April) three out of every four resigned from permanent contracts. This increase has no doubt been concentrated in relatively new permanent contracts, although generally speaking a permanent employee will now be more willing than previously to lose their seniority, given that it will be easier for them to find another job with a permanent contract: 41.2% of all the contracts signed since January 2022 have been permanent, in contrast to the 9.0% in the period 2014-2019.

- 3

During these periods of inactivity, the worker neither receives benefits nor makes any social security contributions, but their

contract remains in force.

Although the Social Security data do not disaggregate these departures by economic sector or professional category, it is logical to assume that voluntary resignations of employees with permanent contracts are likely to be concentrated in activities that had higher temporary rates prior to the reform, such as construction or hospitality, and among workers with less accumulated seniority, since in these cases they have less to lose from resigning: according to data from the Labour Force Survey (LFS), in Q1 2025 more than 70% of employees with permanent contracts have been working in their current job for more than three years, i.e. since before the reform.

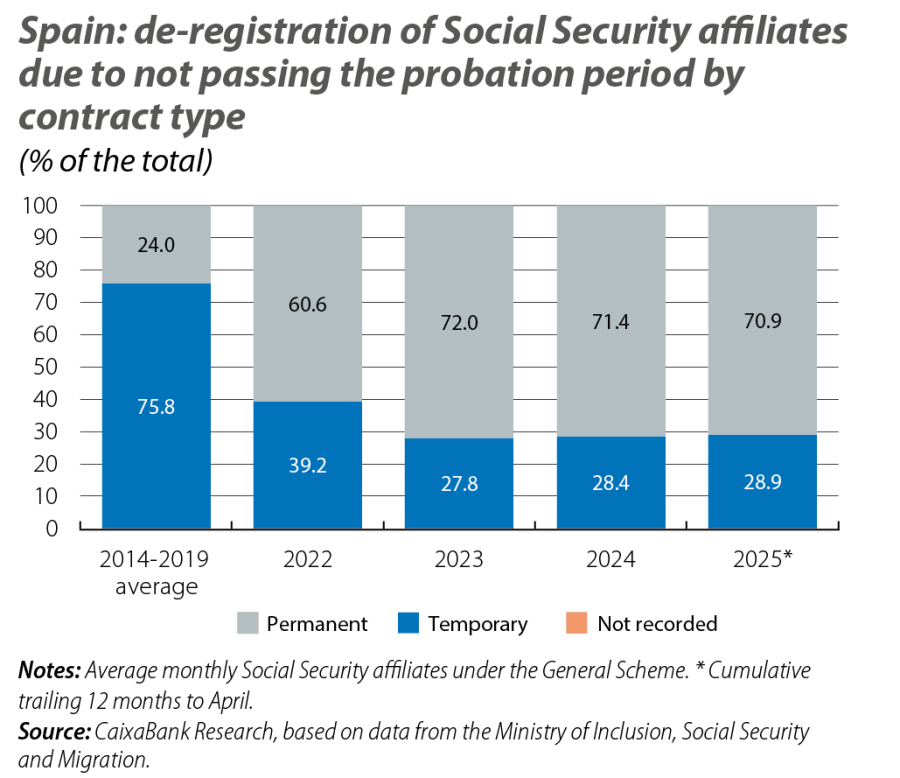

Finally, other types of departure that have experienced a sharp increase in recent years include those that occur as a result of not passing the probation period;4 although they remain a minority (representing just 4.3% of the total), they have almost doubled compared to the pre-pandemic period and now stand at 48,000. In this type of departure, there is also now a greater prominence of permanent contracts (see third chart): in 2025 (data for the trailing 12 months to April), almost 71.0% affected these workers, compared to 24.0% on average in 2014-2019. Although this situation may have raised suspicions that companies could be using the probation period to fill short-term jobs with workers on permanent contracts, the most likely explanation is that permanent contracts are now driving employment more than they did in other similar cyclical phases.

- 4

The probation period must be expressly agreed in the employment contract and may not exceed the maximum duration indicated in the Workers’ Statute (Article 14) or in the collective bargaining agreement currently in force. If the collective agreement does not specify this period, then the maximum trial period will be: for temporary contracts, one month; for permanent contracts, six months for qualified technicians and two months for all other workers, with the possibility that it can be three months in companies with fewer than 25 workers.