What is behind the ECB’s interest rates

The ECB has completed a monetary cycle, leaving the negative rates and unconventional measures of the last decade behind and significantly tightening monetary policy. During this cycle, the ECB has also adjusted the structure it uses to guide and implement monetary policy

The ECB has completed a monetary cycle, leaving the negative rates and unconventional measures of the last decade behind and significantly tightening monetary policy since 2022. Since 2024, with inflation gradually being brought under control, the ECB has been easing its interest rates until inflation has virtually reached the target (2%) and monetary policy has entered neutral territory (depo rate at 2.00%).

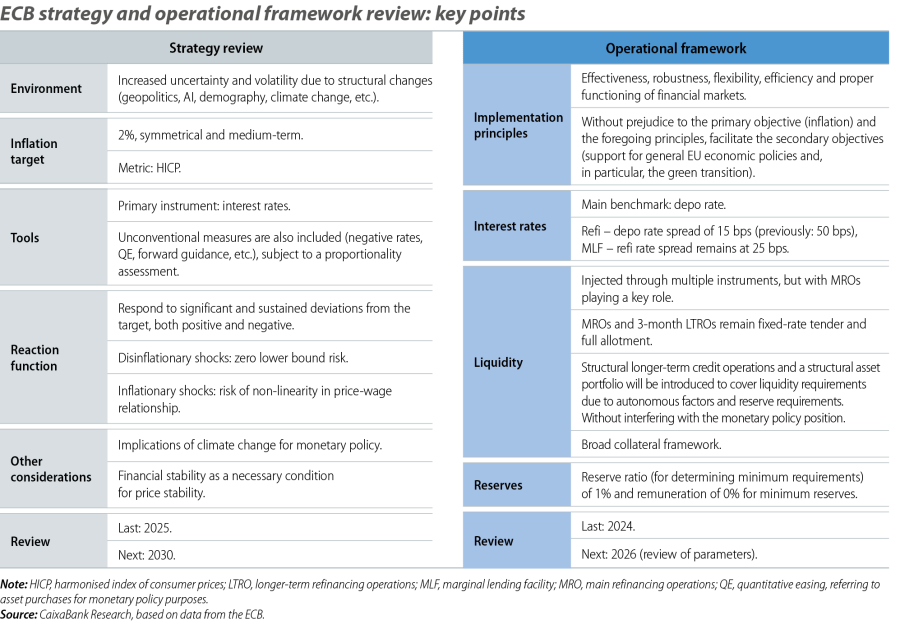

During this cycle, the ECB has also adjusted the structure it uses to guide and implement monetary policy over the course of the business cycle, and it has done so through two spheres: its strategy and its operational framework.

Monetary strategy: a guide for a volatile economy

The ECB’s strategy is the framework that guides its decisions, and it encompasses a vision of the economic environment, monetary policy objectives and a reaction function which sets out how its objective can be achieved given the constraints of the environment. The last time the ECB reviewed its strategy was in 2021: it did so influenced by a decade of low inflation and weak demand and a focus on measures aimed at combating deflation and the threat of the zero lower bound.1 Today the environment is very different, and this change is evident in the ECB’s 2025 strategy update.

The new strategy is based on the view that structural transformations, such as the geopolitical reordering and climate change, result in a more uncertain and volatile economic environment. For the ECB, this means that instances of inflation deviating from the target may become more frequent, persistent and pronounced, and these deviations can be either negative, as in 2010-2019, or positive, as in 2021-2024. Thus, it is not enough to merely reaffirm the key elements of the existing strategic framework; rather, it is necessary to clarify some of the weaknesses identified in recent years.

The continuity of the key pillars provides certainty about the ECB’s course of action. There is no change in the inflation target (2%, symmetric, medium-term and referenced to the HICP)2 or in the official toolbox (interest rates and unconventional measures such as asset purchases, TLTROs and forward guidance). The commitment to climate considerations is also reiterated, as they are relevant to price stability. However, the new strategy incorporates a more balanced reaction function, emphasising that the ECB must react to inflation deviations that are persistent and significant (in volatile times, this allows for a degree of tolerance of moderate deviations, avoiding the temptation to fine-tune monetary policy in response to every new data point), including both negative deviations (as emphasised under the previous strategy) and positive ones. In the same spirit, the ECB has introduced agility as a key characteristic of its unconventional measures, which in the future could translate into the inclusion of «escape routes» in the design of these tools so that, in the event of a sudden change in the scenario (as occurred in 2022), the ECB can shift its monetary policy without the need for an overly slow withdrawal of any stimulus measures in place.3

- 1

The zero lower bound refers to the principle that rates cannot be lowered significantly below 0%. See the Focus «The cost of negative rates:

the case of the Riksbank» in the MR03/2020. - 2

The ECB also reiterated that it would like the HICP to incorporate more representative measures of housing costs. The HICP, which is calculated

by Eurostat, only includes rents that are paid, accounting for less than 6% of the total index. - 3

The mere sending this message is, in itself, an example of an escape route, as it communicates that the ECB wants to be able to quickly abandon unconventional measures if the scenario so requires.

Operational framework: the liquidity transition

The review of the operational framework is much more substantial, at least formally, as in practice it formalises operations that had been introduced out of necessity following the 2008 financial crisis (such as establishing the depo rate as the reference interest rate or maintaining fixed-rate, full allotment [FRFA] in refinancing operations).44 However, the challenge of the operational framework lies in the future: guaranteeing that the ECB’s drainage of liquidity5 does not compromise the implementation of monetary policy. The ECB wants to move from the current environment of abundant liquidity, injected at the time by the central bank itself through unconventional measures, to a world in which the financial system itself determines the liquidity that it wishes to possess: that is, to move from a system governed by the supply of liquidity by the central bank to a system driven by the liquidity demands of financial institutions.

The vision is that a demand-driven system is more efficient (demand is self-satisfying and ensures a proper distribution of liquidity) and robust, as well as reducing the central bank’s footprint in financial markets.66 To implement this, the ECB will make its regular refinancing operations the main source of the central bank’s direct liquidity (especially seven-day MROs, but also 3-month LTROs). In addition, in the coming years the ECB will launch two new instruments for supplying reserves: structural longer-term refinancing operations and a structural asset portfolio. The intention is that these two instruments will not interfere with the position (stimulus or restriction) of monetary policy; rather, being long-term, they will provide stability to financial institutions’ liquidity needs (and not force them into continuous, large-scale refinancing operations).

- 4

Fixed-rate, full allotment: i.e. at the fixed interest rate announced by the ECB, each bank gets as much liquidity as it desires.

- 5

The ECB is undertaking a withdrawal of liquidity from the financial system through the winding down of its asset purchase programmes and the already completed repayment of its TLTROs (long-term loans).

- 6

See the Focus «The ECB, in the midst of a review» in the MR12/2023.

The ECB also anticipates that the markets will become a more significant source of financing. This has influenced the decision to narrow the gap between its refi rate (the cost of borrowing from the ECB through MROs) and depo rate (the remuneration provided for depositing liquidity in the ECB). The ECB has reduced this spread from 50 bps to 15 bps, with the dual objective of making MRO loans more attractive (de facto, the refi rate is reduced by 35 bps) and reducing the volatility of interbank interest rates. At the same time, it aims to maintain a sufficiently wide spread between the refi and depo rates so as to preserve the incentives to lend and borrow in the markets.7 However, the transition will be a gradual one, given that the ECB’s drainage of liquidity is progressing slowly8 (see second chart) and the revival of demand for new liquidity is still only incipient (see third chart).

Taken together, these changes in strategy and operations demonstrate that the ECB has gone through a demanding cycle and has taken note, equipping itself with greater efficiency and flexibility in order to deal with an environment that is at risk from a wide array of shocks (ranging from supply shocks and stagflation scenarios to declines in demand and the risk of the zero lower bound).

- 7

Institutions that lend can obtain remuneration above the depo rate, and those that borrow pay a cost that is less than the refi rate.

- 8

It does so passively, by not reinvesting the principal of the assets acquired years ago under the APP and PEPP purchasing programmes, which are now gradually reaching maturity.