5% of GDP on defence: Why? What for? Is it feasible?

We examine NATO’s reasons and objectives of increasing defence spending to 5% of GDP by 2035, and to what extent it is reasonable to expect the European Union to increase it.

The NATO summit held in The Hague on 24 and 25 June concluded with the commitment by its members to increase defence spending to 5% of GDP by 2035. The defence market is a natural monopsony in which demand is dominated by governments, so these types of commitments have an immediate implication for public finances, especially in a global context of fiscal constraints like the current one.1 In Europe, it also coincides with the desire to give its economy a competitive boost on the basis of the Draghi report,2 so there is significant competition for resources for other strategic areas, such as the green and digital transition. Here, we seek to understand the reasons behind NATO’s commitment, explain what objectives are being pursued and assess to what extent it is reasonable to expect the EU to boost its defence spending in the coming years.

- 1

See the Focus «Debt limits» in the MR01/2025.

- 2

See the Focuses «Draghi proposes a European industrial policy as a driving force to address the challenges of the coming decades» in the MR10/2024 and «A shift in the EU’s political priorities» in the MR04/2025.

Why?

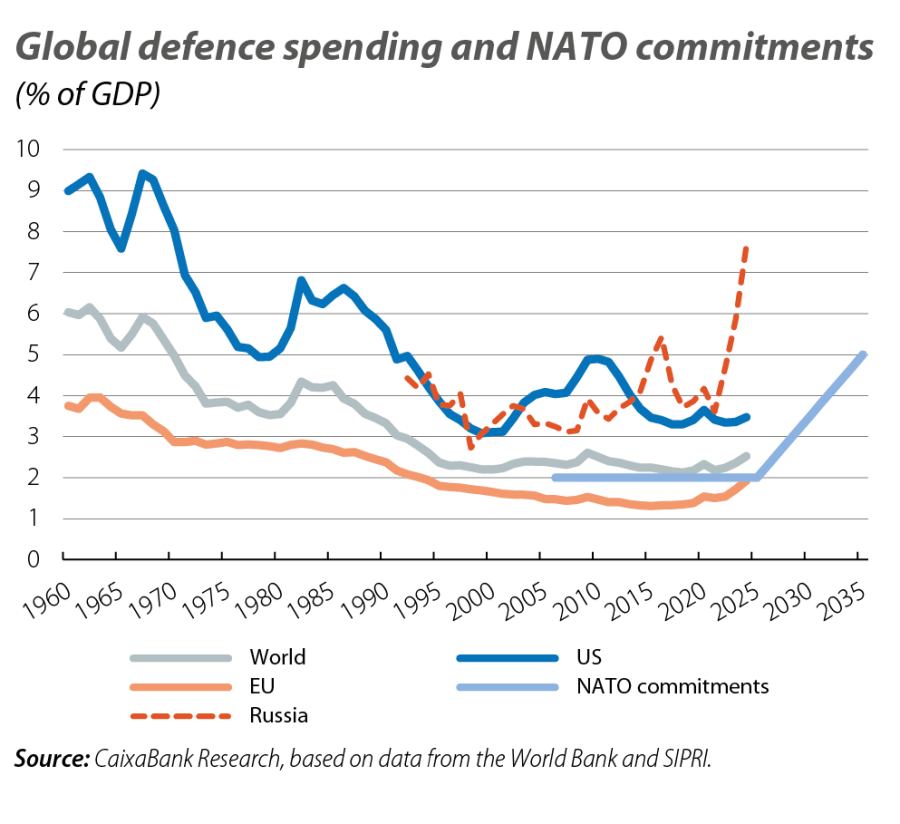

The establishment of defence spending commitments is nothing new to NATO. Indeed, since the Riga summit in 2006, a benchmark of 2% of GDP has been set, and this goal was reinforced at the Wales summit in 2014 following Russia’s invasion of Crimea. The US’ criticisms of the systematic failure of its European partners to meet these targets has not been exclusive to the Trump administrations; they also resonated with Obama and Biden in the White House, and the data show that they are justified in their criticism (see first chart). Another structural element is the mention of the threat posed by Russia to Euro-Atlantic security, materialised since 2022 with the invasion of Ukraine, and which has led to an unprecedented leap in

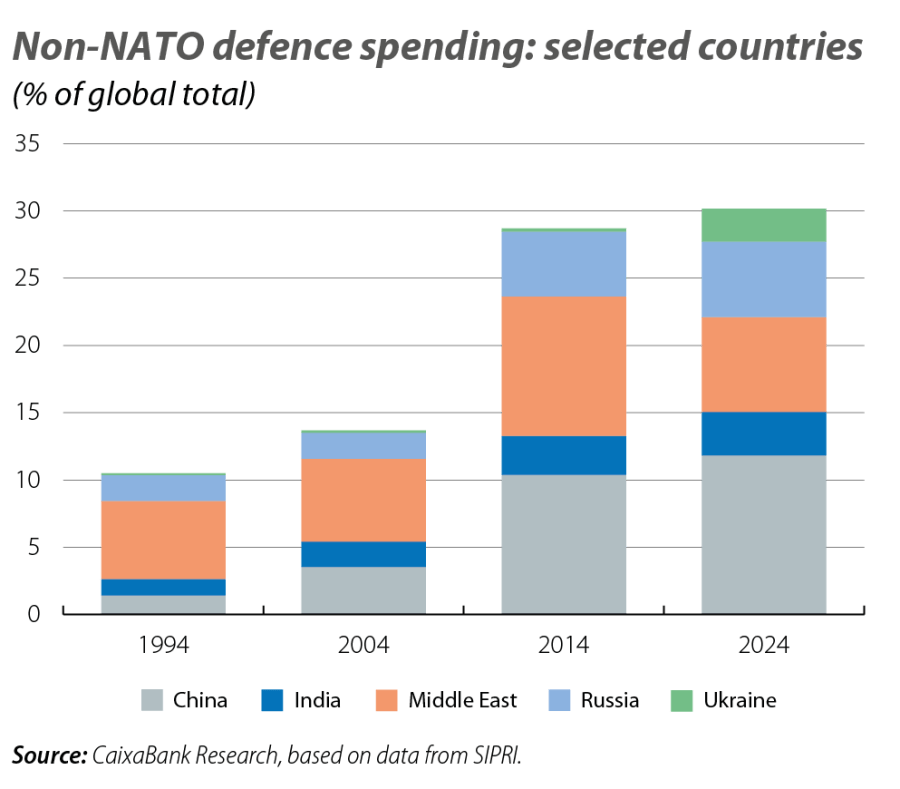

the country’s military spending and its transformation into a «war economy». However, under the current conditions – without any direct involvement of NATO members in a war – none of these factors alone would make it necessary to raise the commitment to 5% of GDP, a figure which the US last met in the final years of the Cold War and throughout the 1960s. Thus, the most reasonable justification should be sought in the desire to have a greater deterrent power in a more polarised geopolitical scenario, in which NATO members have gradually seen their role in the world economy wane, together with their share of absolute defence spending at the global level (from 75% 30 years ago to 55% today). In contrast, the sum of China, India and Russia has steadily increased and today exceeds 20% of the total (see second chart).

What for?

NATO’s new commitment for 2035 is split between 3.5% of GDP to cover essential defence needs and capabilities – mainly equipment and personnel – including for its mobilisation, and 1.5% to protect critical infrastructure, increase civil and digital resilience, to foster innovation and to strengthen the industrial base. Thus, the first component is one that seeks to ensure a faster response in the short term to conventional threats and aggressions, while the second one would provide member countries with a more robust and broad-spectrum autonomous layer of security. Meeting these targets is undoubtedly a driving force behind more resources being employed, but qualitative considerations are just as relevant, if not more so.3 In this regard, NATO has stressed the importance of a cooperative and coordinated systemic approach, with common standards and joint public procurement processes that facilitate the interoperability and interchangeability of equipment and weapons, as well as a more secure supply chain for the provision of critical materials to the defence industry.4 This same diagnosis has been carried out by European institutions in recent years,5 presenting, as highlighted in the Draghi report, three particularly marked weaknesses of the defence sector vis-à-vis the US: the fragmentation of its internal market – which affects both its industry and governance – the high external dependence and the low percentage of spending on research, development and innovation.

- 3

Carnegie Endowment (2025). «Taking the pulse: does meeting the 5 percent of GDP target enable Europe to confront the Russian threat?».

- 4

NATO (2024). «NATO industrial capacity expansion pledge», and NATO (2024) «Defence-critical supply chain security roadmap».

- 5

EEAS (2022). «A strategic compass for security and defence», European Commission (2022), «Defence Investment Gaps Analysis

and Way Forward» and European Commission (2025), «White Paper for European defence - Readiness 2030».

Is it feasible?

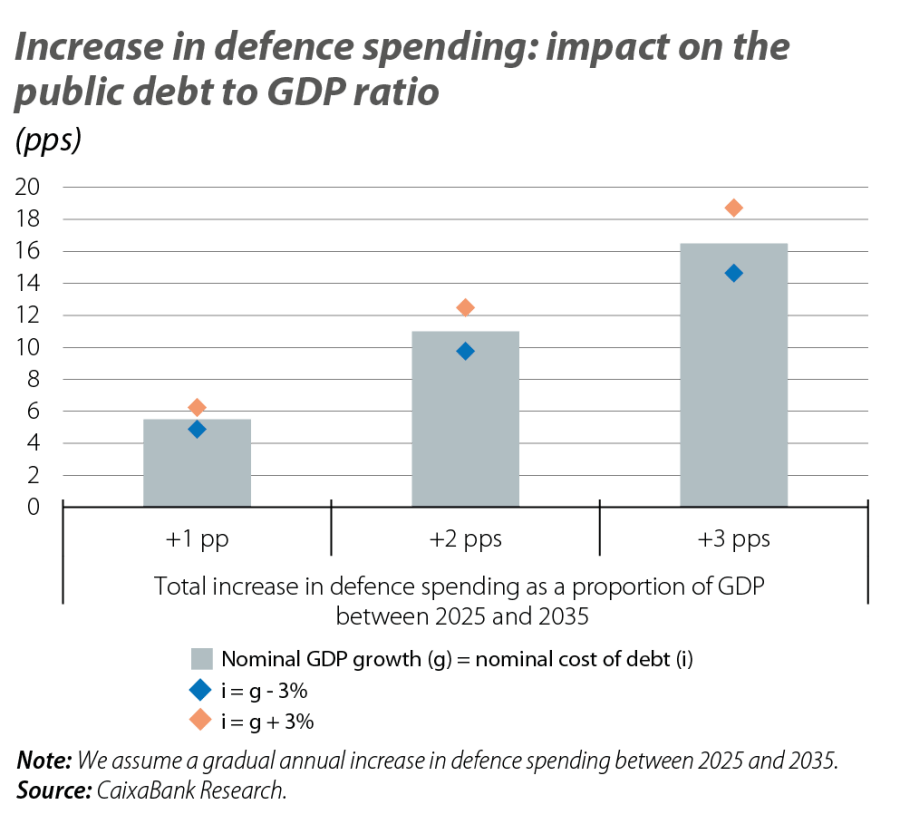

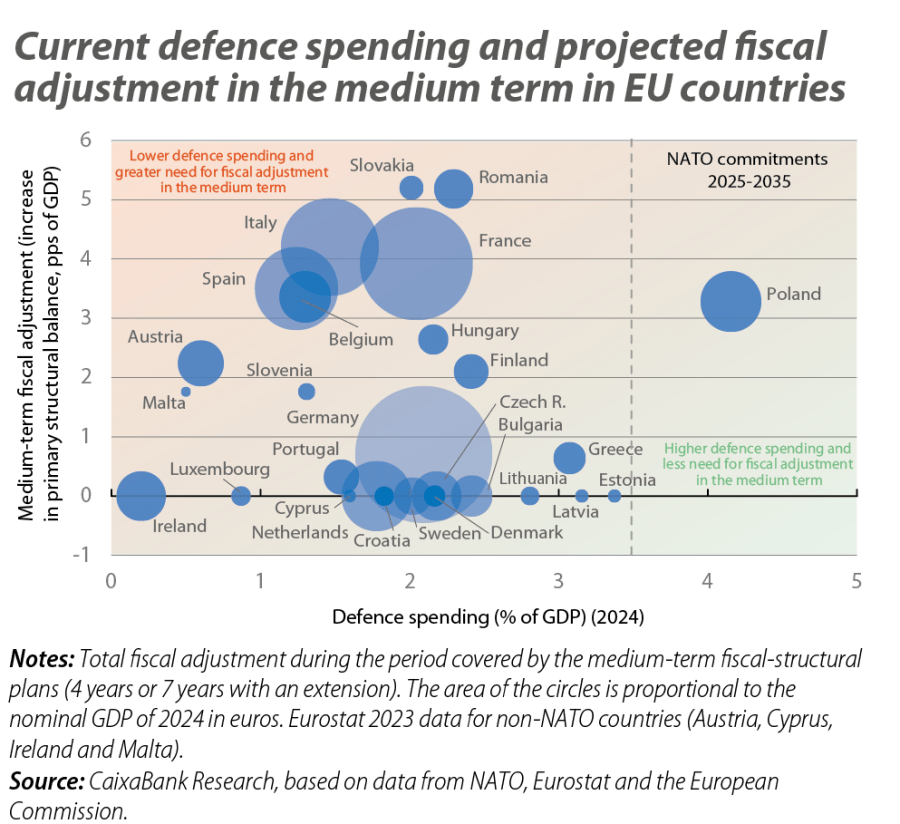

In the EU, the various initiatives proposed by the European Commission to finance the expansion of defence spending leave the bulk of the fiscal effort in the hands of Member States. On the one hand, the first measures presented in March and already endorsed by the Council – which include a new 150-billion-euro loan instrument (SAFE) to promote joint purchases, and the possibility of deviating from the spending rule over the next four years by up to 1.5% of GDP – has generated little enthusiasm among Member States with limited fiscal margin. These measures fail to cushion the significant impact that the new defence commitments will have both on public debt (see some scenarios in the third chart),6 with risks of pushing up the cost of sovereign financing, and on additional adjustments to those already required by the medium-term fiscal plans (see fourth chart).7 This latter impact could have potential implications for income growth and distribution, depending on the value of the various fiscal multipliers and on which taxes and/or expenditure items the compensatory measures are concentrated in.8 In fact, in this context, Spain, France and Italy have not requested the activation of the escape clause, significantly reducing the scope of this measure to around 200-300 billion euros compared to the 600 billion initially estimated. On the other hand, the appetite of the so-called «frugal countries» to push for a new NGEU-style joint debt-issuance spending programme seems to have been diluted in recent months, as priority has instead been given to pursuing national proposals, as in the case of Germany. Moreover, the increase proposed by the European Commission for the next budget cycle9 is dwarfed by the magnitude of the commitments reached within NATO.

- 6

The scenarios in the third chart show the increase in public debt derived exclusively from different increases in defence spending (1 point, 2 points or 3 points of GDP between 2025 and 2035, distributed proportionally over each of the next 10 years), and in each case the sensitivity to a negative, neutral or positive gap between nominal GDP growth and the nominal cost of public debt. We assume that the increase in defence spending is not compensated for by higher taxes or reduced spending elsewhere.

- 7

See the Focus «The new EU economic governance framework» in the MR01/2025.

- 8

Regarding fiscal multipliers, see V. Sheremirov and S. Spirovska (2022) «Fiscal multipliers in advanced and developing countries: Evidence from military spending», Journal of Public Economics.

- 9

See the Focus «The 2028-2034 EU budget: An impossible mission?» in this same Monthly Report.

At this juncture, in the current geopolitical scenario, the motivations for wanting to boost defence spending above current levels are understandable. There are also aspects that need to be strengthened in public procurement processes and in Europe’s defence industry in order to meet the emerging challenges with guarantees. Nevertheless, the aspiration of reaching 5% of GDP is undoubtedly highly ambitious. Taking a reference level of 3%-3.5%, in 10 years this figure would compensate for the deficit in defence spending accumulated by European governments in recent decades – a considerable effort. The fiscal bill could be lowered through a precise identification of critical priorities, better coordination to reduce costs and avoid duplication, and encouraging synergies with the private sector in the field of innovation; this would also allow progress to be made in other strategic areas in order to raise the potential growth of the European economy.