The effects of ageing on growth and policy tools to mitigate them

The current demographic transition should lead, ceteris paribus, to a significant slowdown in economic growth over the coming decades, in both advanced and emerging and developing countries. Only an ambitious implementation of a set of policies can significantly cushion its effects.

The current phase of the global demographic transition, characterised by slowing population growth and an ageing population (for further details, see the article «Demography and destiny: the world that awaits us in 2050 with fewer births and longer lifespans» in this same Dossier), involves a series of transformations and broad-spectrum challenges for the economy, which seem to have cast a shadow over the prospects for global growth over the coming decades. However, the future is not written in stone and it can be shaped with the right policies. Proof of this is the fact that the «demographic dividend» that Africa has enjoyed for decades has not been reflected in significant economic development in the region, in contrast to the dynamism of Southeast Asia, which has become an engine of global growth in the last 25 years. Indeed, this dynamism has been led by China, which has managed to transform its economy into a global competitor, including in high-tech products, despite a relatively ageing population.

The diminishing role of demographics in growth

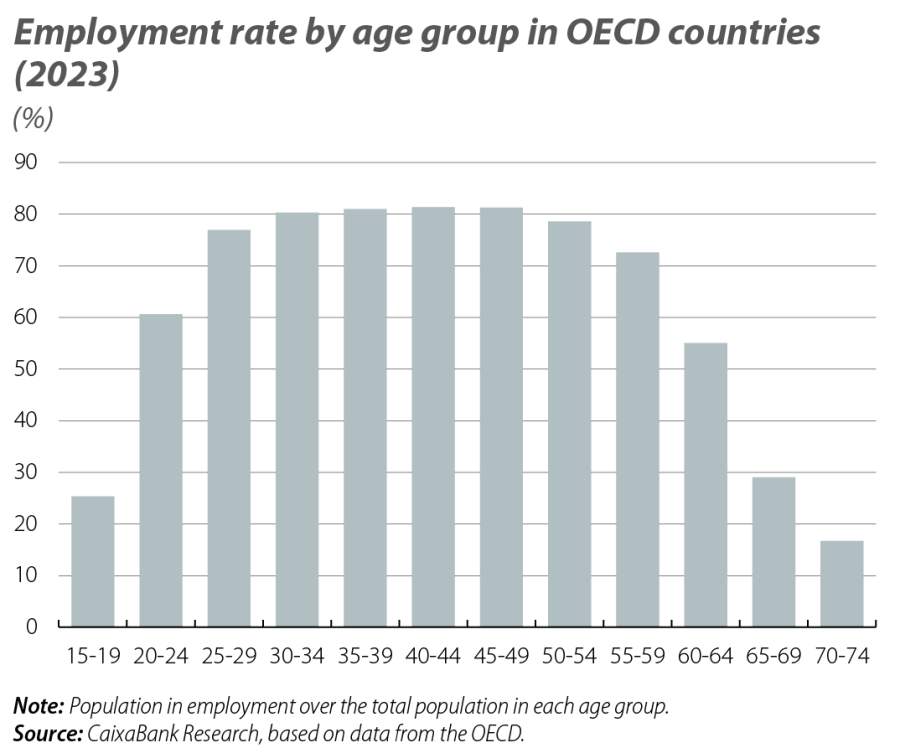

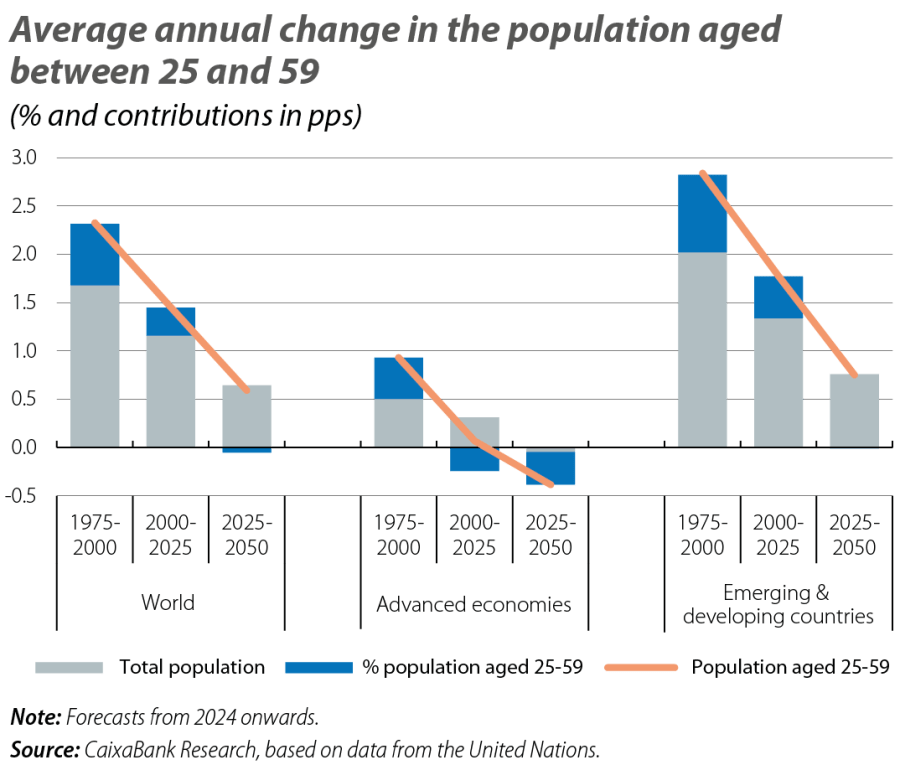

Taking into account that a country’s economic activity depends on the volume of its resources and the way in which they are used and combined, the current demographic transition poses two simultaneous challenges. On the one hand, lower population growth slows down the increase in available resources, in this case, the labour factor. On the other hand, population ageing causes the most utilised labour resources – usually the population between 25 and 59 years of age (see first chart) – to decrease as a share of the total. If we look at projections by the United Nations,1 the combination of these two factors seems to lead, ceteris paribus, to a significant slowdown in economic growth in the coming decades. This is the case both for advanced countries, where the total population has already stagnated at best, and especially for emerging and developing countries, where for the first time the share of people of working age will decline relative to the population as a whole (see second chart).2

Scope for closing the gender gap and prolonging working life

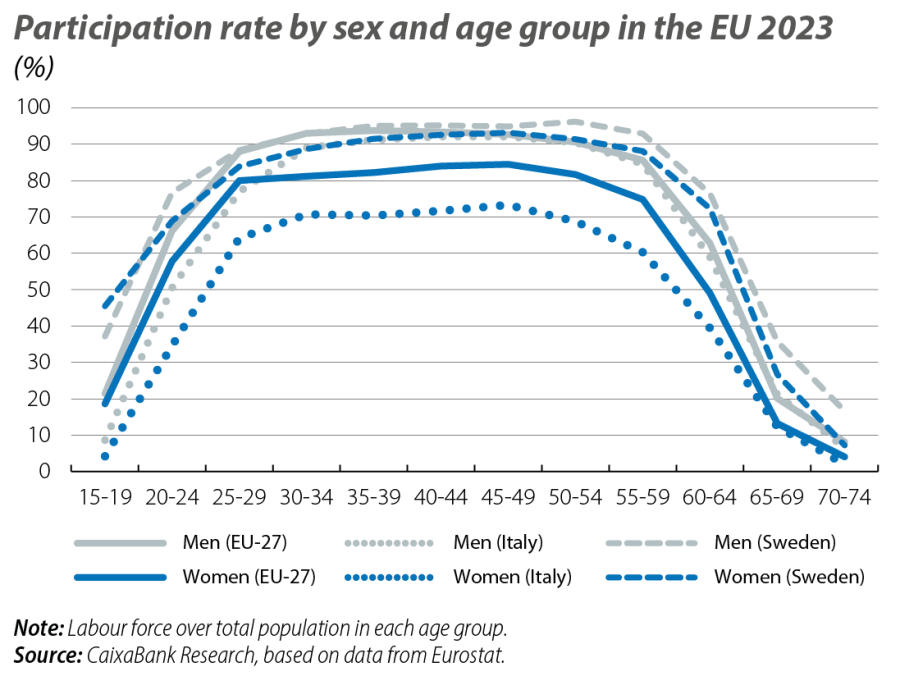

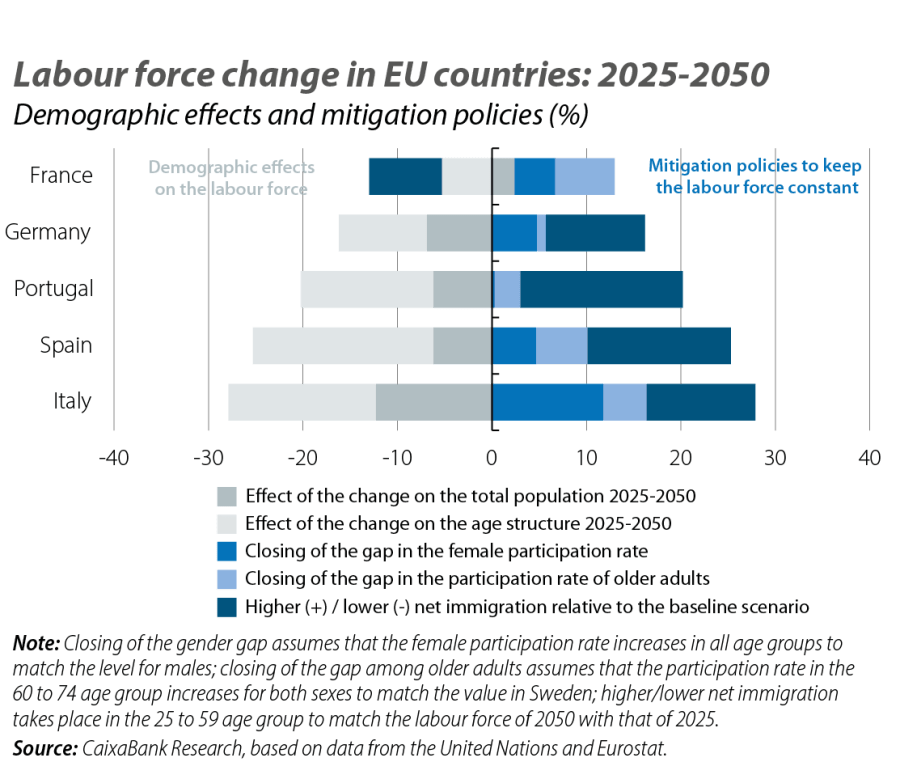

Among the elements that could help mitigate the effects of the current demographic transition on economic growth, one of the main areas of action is policies aimed at increasing the supply of labour. In this regard, despite the convergence observed in recent decades due to social and educational factors,3 even today stark differences persist in the labour force participation rate between countries, as well as between population groups within these countries, with the lowest rates found among women and with a sharp decline in workers from 60 years of age (see the third chart for the EU as a whole and the contrast between two of its member countries, Italy and Sweden). Some of the levers that can help boost participation among women include, above all, policies that facilitate a balance between work and family life, such as flexible part-time work arrangements, non-deterrent tax treatment for secondary earners and adequate provision of early childhood education services.4 On the other hand, in order to extend people’s working lives, incentives can be implemented to align the effective retirement age with the statutory one, to promote the compatibility of retirement and certain forms of employment, to bolster active policies with lifelong learning and to improve the health conditions in old age.5 Also, given the differences between world regions in the stage and intensity of these demographic changes and the persistence of wide gaps in economic development, managing migratory flows will continue to play an important role.6 Only an ambitious implementation of this set of policies can significantly cushion the effects of the demographic transition (see example for different EU countries in the fourth chart, based on UN projections).7

- 3

C. Fernández Vidaurreta and D. Martínez Turégano (2018), «Labour market participation rate in the euro area: performance and outlook, a long-term view», Bank of Spain Economic Bulletin.

- 4

J. Fluchtmann, M. Keese and W. Adema (2024), «Gender equality and economic growth: Past progress and future potential», OECD.

- 5

IMF (2025). «The rise of the silver economy: global implications of population aging», World Economic Outlook.

- 6

See, for example, the case of the euro area after the pandemic: O. Arce, A. Consolo, A. Días and M. Weissler (2025), «Foreign workers: a lever for economic growth», ECB.

- 7

In the case of Spain, the projections produced by the National Statistics Institute (INE) differ significantly from those of the United Nations, mainly with regard to immigration flows. Specifically, while the latter anticipate an average of 60,000-70,000 net entries between 2025 and 2050, the INE’s projections place this figure between 350,000 and 400,000 people. Using the latter as a reference, we estimate that the labour force in Spain would remain relatively stable during this period.

Productivity to the rescue (driven by AI)?

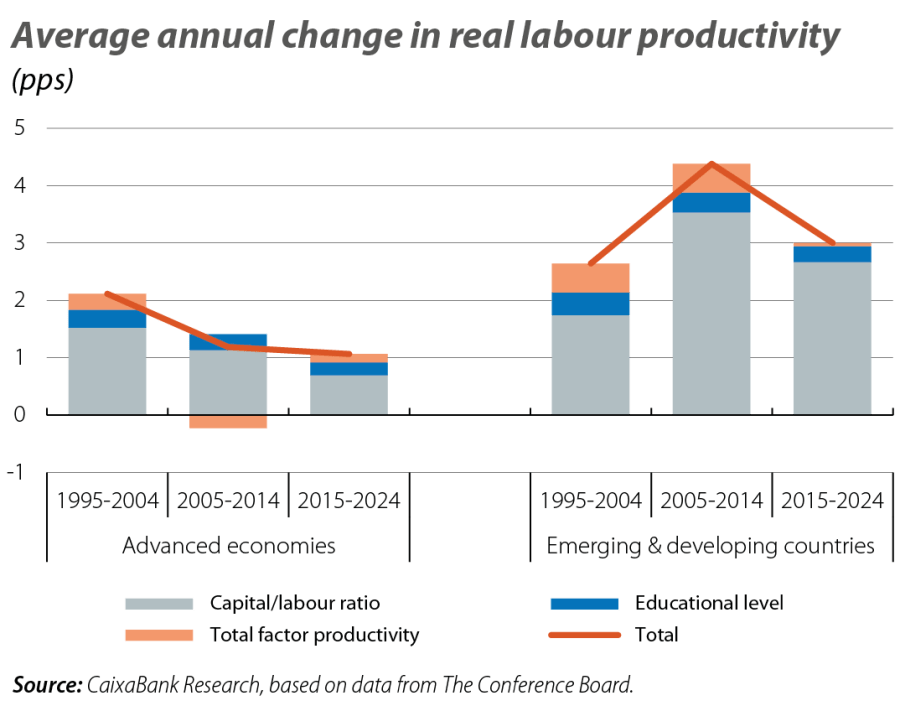

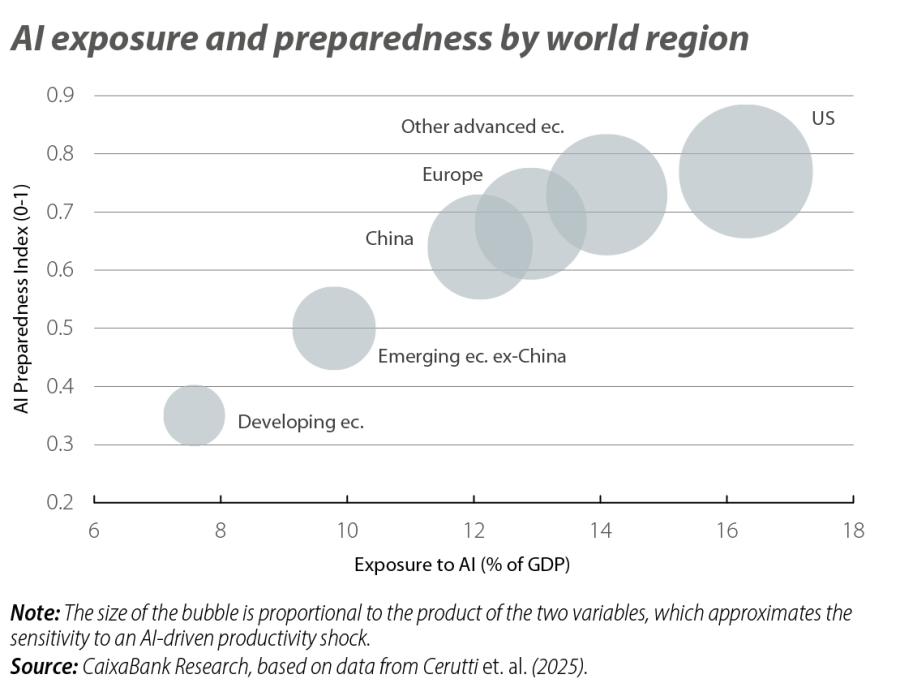

In addition to greater use of the labour factor, its more efficient use combined with capital resources is also a key source for overcoming the determinism of the current demographic transition. Over the past few decades, labour productivity has continued to increase at a steady pace globally, driven by structural change and macroeconomic stabilisation in emerging countries, which have facilitated efficiency gains, improvements in education level and the accumulation of productive capital (see fifth chart). However, the effect of these processes tends to be progressively exhausted as the degree of economic development advances and sectoral tertiarisation becomes more pronounced. Moreover, we observe a practical stagnation in the translation of technological advances to total factor productivity (TFP).8 In this regard, recent developments in the field of artificial intelligence (AI) have opened the door for this general-purpose technology to boost TFP across a broad spectrum of sectors, particularly those involving more cognitive tasks, as well as accelerating innovation processes. However, there is still significant uncertainty over the degree of complementarity/substitutability of AI with the labour factor,9 leaving ample scope for future scenarios. Some baseline estimates place the increase in labour productivity in the US in the range of 1%-1.5% per year,10 which would offset the demographic brake on GDP growth discussed above. In the rest of the world, the expected gains would likely be more moderate given the reduced exposure to and preparedness for the adoption of AI, including institutional aspects, the rollout of digital infrastructure and vocational training (see sixth chart).11

- 8

Changes in total factor productivity measure the variation in production in an economy that is not explained by increases in the productive factors (capital and labour); for example, through these factors being used more efficiently.

- 9

D. Acemoglu (2024), «The simple macroeconomics of AI», NBER.

- 10

M. Baily, E. Brynjolfsson and A. Korinek (2023). «Machines of mind: The case for an AI-powered productivity boom», Brookings; Goldman Sachs (2023), «Generative AI: hype, or truly transformative?».

- 11

E.M. Cerutti et al. (2025). «The Global Impact of AI – Mind the Gap», IMF.

A comprehensive strategy to address the demographic challenges

Policies aimed at increasing the labour supply and boosting productivity have a high potential to offset the effects of the demographic transition. However, their effectiveness will depend decisively on three factors. Firstly, it will depend on the existence of favourable conditions for business activity and job creation. In the EU, this need has been echoed in the Competitiveness Compass,12 which seeks to revitalise the growth capacity of the European economy through improvements in the regulatory framework of the internal market and the mobilisation of capital towards strategic investments. Secondly, the range of professional skills needs to be adapted to technological changes, the green transition and new patterns of demand in an ageing society. To this end, active labour market policies must minimise the costs of adjusting to this new reality and firms must adapt their job positions, paying particular attention to jobs at risk due to task automation, increasingly shaped by advances in AI. Thirdly, the set of public policies must be adapted to promote further improvements in citizens’ welfare at the same time as maintaining fiscal discipline,13 while private actors will have to adjust their consumption and investment decisions to the new income and wealth conditions across the life cycle.14 In both cases, the distributional effects of the ongoing changes will also be relevant for determining the magnitude of the challenges.

- 12

See the Focus «A shift in the EU’s political priorities» in the MR04/2025.

- 13

See the articles «The impact of ageing on public finances: a major challenge for Spain and Europe» and «Levers to mitigate the impact of demographics on public finances: the case of pensions» in this same Dossier.

- 14

See the article «Will an ageing society pay lower interest rates?» in this same Dossier.