Monetary and fiscal tribulations: the long road towards Abenomics

Japan's policies to manage aggregate demand have been immersed in controversy for decades. Although the criticism has sometimes been exaggerated, it is true that, with hindsight, some episodes can be identified in which a better course of action might have been taken. The euro area could learn some useful lessons in this respect.

The root cause of Japan's complications began in the middle of the 1980s. On the basis of excellent economic figures, a trio of bubbles started to form in bank credit, real estate and the stock market. All three reached formidable proportions as the economic authorities passively watched on. This is the first reason for criticism: neither monetary nor macroprudential policy challenged these excesses. Certainly, such blame can also be laid at the door of the United States (in 2000 and in 2007) and of the euro area (in 2008, in various periphery countries). The lesson from all these episodes should be thoroughly learned: it is a good idea to slow up credit booms during economically strong periods. However, there is much more discussion regarding the right response when such bubbles burst and it was in such a situation that Japan became stigmatised.

The Japanese bubble burst in 1990. The slump in the stock market and real estate was of a similar size to the 1929 crash in the United States. The banking sector was the hardest hit, first of all by losses in its industrial stock portfolios and afterwards by non-performing loans and low returns. The non-financial corporate sector was also severely affected with its stock losing value and large debts, while the affect on household finances was less severe but still considerable. On the other hand, the government had a relatively low level of debt at the start of the crisis. A thorough comparison with the overall situation of the euro area in 2008 would identify significant differences between these two episodes which should not be ignored by any detailed analysis. However, there are two similar features that leave their mark: serious problems in bank solvency and high private sector debt: a challenging context for fiscal, monetary and financial regulation policies.

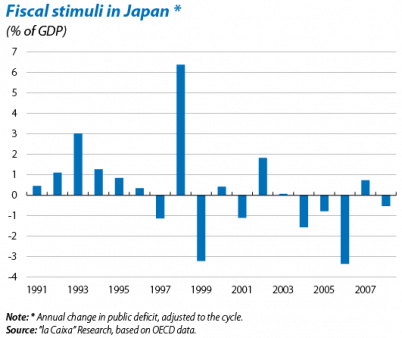

Fiscal policy was the first line of defence deployed in Japan. As from 1990 the government had already embarked on ever-increasing budget expansion to revive the economy or at least soften the blow to the private sector. Net public debt was 12% of GDP in 1990, leaving room to increase the government deficit. Stimuli reached their peak in 1993 and then were eased given a few signs of economic recovery in 1995-1996, although in retrospect this incipient improvement led to an error of judgement. In 1997 the government implemented a programme of fiscal consolidation which included a notable VAT hike (with net public debt still at a modest 34% of GDP), which had a huge dampening effect on the economy. It is only fair to mention the emergence of another negative element unrelated to the Japanese authorities: the financial crisis of South East Asia in 1997-1998. Japan entered in recession and its deflationary period began. Since then fiscal policy has lacked definition and any clear strategy, being conditioned by the accumulation of public debt, in turn due to meagre growth and the demographic factor (net debt reached 82% of GDP in 2006 and 139% in 2014). For some analysts the «stop and start» nature of Japan's fiscal policy between 1990 and 2009 made it less effective while other criticisms are directed at the composition of stimuli. In terms of expenditure, Japan made the mistake of allocating a large amount of resources to public works that were not very productive. In terms of taxation the authorities have not managed to design a system that can generate enough revenue whilst also taking care of incentives for companies and households.

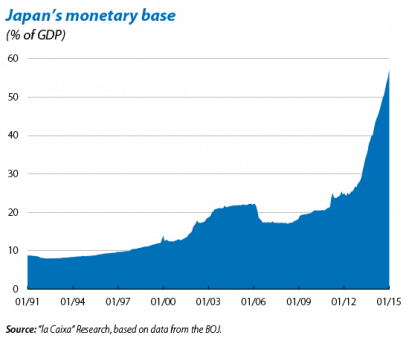

Monetary policy was Japan's second line of defence. With the benefit of hindsight and the experiences of the last few years of the Federal Reserve (Fed) and the European Central Bank (ECB), we can state that Japan's monetary stimuli in the 1990s were timid. It is true that the Bank of Japan (BOJ) reacted quickly to the collapse of the bubbles, starting to lower the official interest rate in 1990, but it did so slowly: from 6% to 0.5% by 1995. Another significant figure is that, between 1990 and 1997, the BOJ's monetary base only went from 8% to 10% of GDP. This contrasts with the extremely aggressive and fast response by the Fed in the US after its bubble burst in 2007, while the ECB's actions since 2008 place it somewhere between both these countries, although it has shifted from a moderate stance in 2008-2012 towards a more aggressive position since 2013.

Several factors help to explain the choices made by the BOJ since 1990: its analysis of the situation, its preferences given the trade-offs and the country's institutional and international environment. But perhaps the biggest mistake was not realising the singular nature and seriousness of a crisis fuelled by bank solvency and liquidity. The BOJ's tolerance of zombie banks turned out to be fatal; it stopped any early monetary stimuli from impacting the real economy sufficiently, while also maintaining a weak layer that finally broke up with the Asian and fiscal shocks of 1997. Several important banks went bust that year but it was not until 2003 that public agencies were set up to restructure bank debt in any centralised way.

Once the bank problem was more or less back on track, monetary policy in the 2000s had to tackle the spectre of deflation. Once again the BOJ decided to err on the side of caution: with the official interest rate already close to zero, it slowly and hesitatingly applied some quantitative easing measures but these were aimed at providing liquidity to convalescent banks and the effects were hardly felt by the private sector. In addition to the doubts expressed by the BOJ itself regarding its diagnosis (based on the possible influence of the demographic factor as a non-monetary cause of deflation), this moderate position taken up by Japan's central bank must be seen within the context of its goals and preferences. In 1998, just before the deflationary period began, a law gave independence to the BOJ, establishing price stability as its prime objective but without setting any concrete, explicit figure. Given a low intensity deflation well-tolerated by Japanese society (together with a very low unemployment rate), the BOJ probably decided that the costs and risks of more aggressive actions outweighed the potential benefits. It was affected by its fear of losing anti-inflationary credibility and of being out of step with an international environment that was moving in a different direction, but this changed radically with the Western crisis of 2007-2008. Given the huge impact of this shock, the Fed's overwhelming response, the yen's appreciation and the support obtained in elections in 2012, the Prime Minister Shinzo Abe instigated an authentic revolution in economic policy, called Abenomics.

The effective deployment of the three areas that make up Abenomics is uneven at present. Structural reforms are few, at least for the time being. Fiscal policy is still restricted by debt so the initial spending programme in 2013 had to be counterbalanced with a VAT hike in 2014. But the aggressiveness of monetary policy is beating all records. An asset purchase programme has been implemented totalling 80 trillion yen per year (more than 15% of nominal GDP in 2014), which will last until inflation reaches the 2% zone. These purchases cover a wide range of assets but most are government bonds; in fact, it is the country that comes closest to genuine debt monetisation. There can be no doubt that the pros and cons of quantitative monetary policy, so widely debated in general, are going to be put to the test in Japan over the next few years. For the moment, inflation and inflation expectations have risen to positive figures although they are still far from 2%, while the improvement in terms of GDP growth is more debatable.

The euro area can draw some conclusions from Japan's long experience. The first is the need to act with caution during incipient recoveries and the importance of establishing intelligent road maps when removing stimuli. The second is that not all expenditure items are equal. Thirdly, it is expedient to be forceful when acknowledging the need for monetary stimuli (the consensus here is not unanimous but almost), while perhaps the most useful lesson is that resolving problems in the financial sector helps to boost the effectiveness of stimuli. Lastly, the international environment cannot be ignored: Japan's recovery in the 1990s was hit hard by the Asian crisis while the United States' policies since 2007 have acted as a catalyst for the new Abenomics. Only time will tell if this is for the best.

Jordi Singla

Macroeconomics Unit, Strategic Planning and Research Department, CaixaBank