The Belt and Road Initiative: a double-edged sword? (part I)

Through the BRI, China has sought to establish alliances and improve regional connectivity through infrastructure investments and economic integration in the Eurasian continent, as well as in Africa and Latin America.

Over the past decade, China has become a key player in global trade and in foreign direct investment (FDI) flows into emerging economies. Anchored in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI),1 launched in 2013, its ambitious foreign policy has sought to establish alliances and has focused on improving regional connectivity through investments in infrastructure and economic integration in the Eurasian continent, as well as in Africa and Latin America.

The BRI offers reduced transport costs and times, generating «agglomeration economies» in the manufacturing sector and facilitating the mobility of resources. On the other hand, participation in the BRI can promote Chinese FDI and support the modernisation of the participating countries’ productive fabric.2 Also, the trade and investment channels are among the most important for understanding the economic effects of the BRI. In a series of three articles, we will take a closer look at the trade channel, using detailed data on international trade flows.

- 1

The name refers to the ancient Silk Routes – commercial networks that connected Asia, the Middle East and Europe from the 2nd century BC to the 15th century AD. Since the BRI was announced in 2013, each year new countries have signed the «Memorandum of Understanding» in order to participate in the programme. Most of the participating countries did so between 2013 and 2018, the latter being the year with the most accessions (62 in total), and are located in Asia and Africa – regions made up mostly of countries with greater infrastructure investment needs and allowing China to extend its regional influence. In total, more than 140 countries form part of the initiative. Although there is no official list of participating countries, we use the definition by C. Nedopil (2025) «China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Investment Report 2024», Green Finance & Development Center.

- 2

F. Zhai (2018) «China’s Belt and Road Initiative: A preliminary quantitative assessment», Journal of Asian Economics, pages 84-92, estimates that the BRI could have a positive impact on trade flows and GDP, especially if it is accompanied by institutional improvements. See also J. Bird, M. Lebrand and A. Venables (2020) «The Belt and Road Initiative: Reshaping economic geography in Central Asia?», Journal of Development Economics; and H. Yeung and J. Huber (2024) «Has China’s Belt and Road Initiative positively impacted the economic complexity of host countries? Empirical evidence», Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, pages 246-58.

China’s exporting profile: from manufacturing giant to technological power

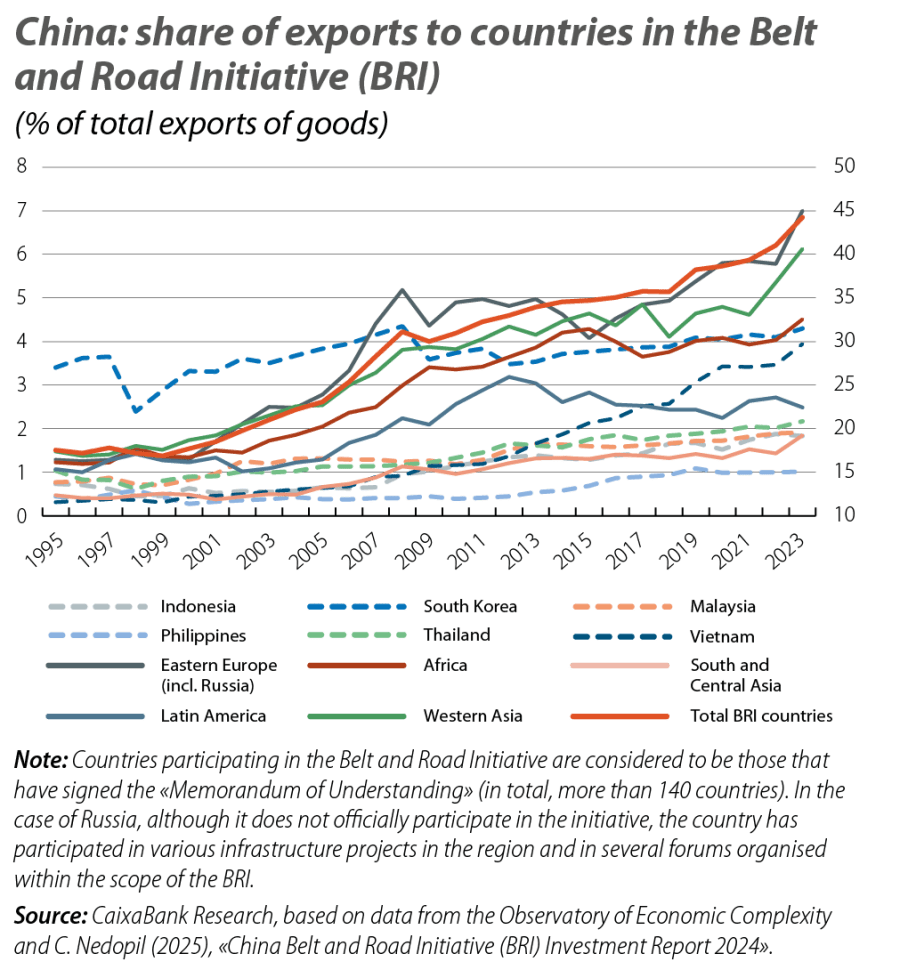

Just as the BRI intended, China has managed to increase its share of global exports from just over 5% at the turn of the century (around 500 billion dollars) to 15% (or 3.5 trillion dollars) today, while at the same time exports to countries participating in the BRI have gone from representing 20% to more than 40% of the total. In addition, in recent years, there has been a rapid diversification of export destinations, with the share of countries participating in the BRI increasing by some 10 pps.3 China has also developed links with new markets and improved the infrastructure of countries that were beginning to gain prominence as export destinations, creating alternative trade routes to traditional export destinations, such as the US, in the face of an imminent escalation of trade frictions.

By sector, the increase in China’s exports to BRI countries has been widespread, albeit with some nuances. For example, the share of exports of furniture and related products to these countries has grown by 15 pps between 2018 and 2023 (from 23% to 38%), after remaining practically stagnant in the previous decade, while the share of car exports has grown by 14 pps (from 40% to 54%) and has reached a new peak since 2013 (when it stood at 50%), during a period of strong growth in the sector. There have also been accelerations in sectors such as electrical products and electronics, while in metals their market share has remained stable since 2018.

- 3

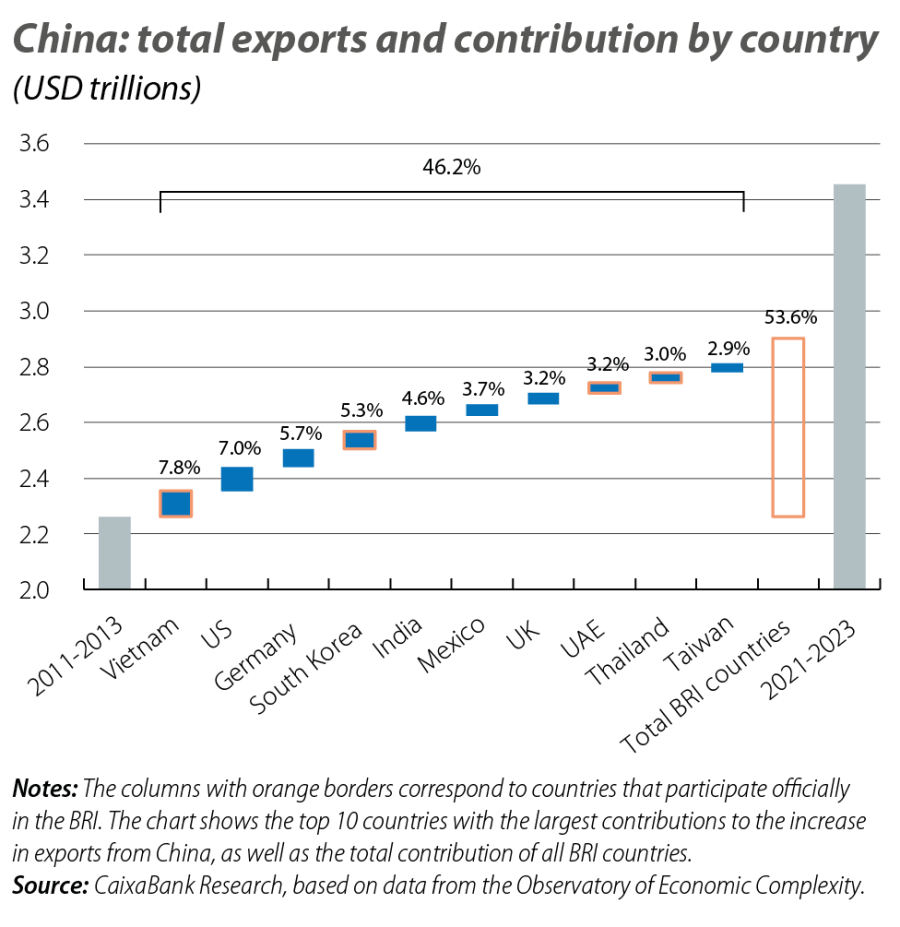

The Herfindahl-Hirschman (HH) index of geographical concentration of China's exports has declined from 655.9 in 2011-2013 (652.4 in 2016-2019) to 451.6 in 2021-2023, indicating a rapid geographical diversification of its exports. On the other hand, the product concentration index (at the HS4 level) of Chinese exports has remained stable over the period (at around 170 points).

The new Silk Road: strategic axis of Chinese global trade

Over the past decade, BRI participating countries account for almost half of China’s export growth (see second chart). Among the top 10 destinations that have contributed the most, we find four countries that form part of the initiative (15 in the top 30), the most prominent of which is Vietnam. This country has contributed 7.8% to China’s total export growth over the period in question, making it the fifth most important destination for Chinese exports, having barely made the top 20 a decade earlier. Other Asian countries participating in the BRI, such as the United Arab Emirates, Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines have also seen substantial growth, as well as some Eastern European countries, while Latin America and Africa have recorded significant growth since 2016-2018. On the other hand, while the US has contributed significantly to China’s export growth over the last decade as a whole (7% of the total), the dynamics have been rapidly changing. Whereas China’s exports to the US grew by more than 20% up until 2016-2018, they have contracted in the years that followed. Hence, the share of exports to the US has fallen from 20% to around 15% of the total.

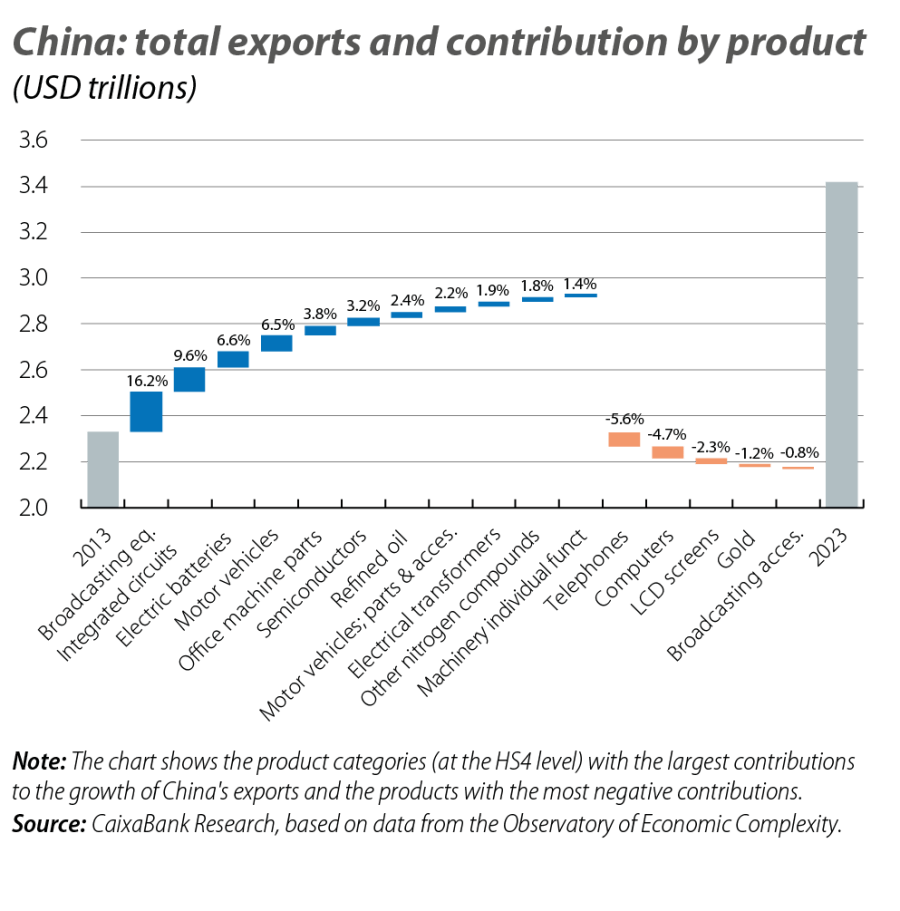

In addition to diversifying the geographical distribution of its exports, an analysis at the product level reveals profound changes in Chinese value chains. As a witness to its rapid technological evolution, China now ranks 21st in the Economic Complexity Index (ECI) produced by the Observatory of Economic Complexity, compared to 31st back in 2013 and below 50th up until 2004. In the past decade, the biggest contributions to China’s export growth have come from sectors such as electronics and machinery, in which the country has acquired a key role. Particularly noteworthy are electric batteries and motor vehicles, with contributions in excess of 6% and very high nominal growth rates. Overall, exports of these goods have increased 12-fold in the period. On the other hand, also of note is the contribution from refined oil, exports of which have doubled in 10 years, mainly to Asian countries.

The distribution of each country’s trade flows depends on multiple economic, geographical, institutional and geopolitical factors. However, it is clear that China’s efforts over the past decade – anchored in several complementary initiatives, both externally (such as the BRI) and domestically (such as its Made in China 2025 industrial policy) – have achieved a profound transformation of its productive structure and of its trade relations with the rest of the world, with obvious geopolitical consequences.