Is there «early» evidence of de-risking? (part II): the EU

Having laid out the complex trade relationship between the United States and China, we continue to analyse the phenomenon of de-risking among the major economic powers, focusing on the European Union.

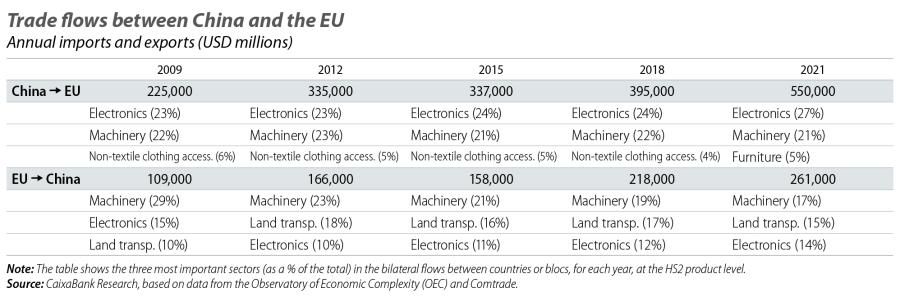

Between 2018 and 2021, we experienced a first wave of trade tensions in a conflict that was concentrated in the US-China axis. In that period, EU imports from China increased by almost 40% (see first table),1 but since 2021 the tensions have spread and the EU has been adopting a more assertive stance towards China, particularly following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

- 1. In this period, US imports from the EU have grown by 12% (to around 450 billion dollars per year). Also see the Focus «Is there «early» evidence of de-risking? (part I): the US and China», in this same report.

In 2021, 22% of imports of goods from outside the EU came from China (around 550 billion dollars), up from 18% between 2015 and 2018 and marking a record level. In the electronics sector, China’s share of EU imports in 2021 stood at 47%, compared to 38% up until 2018.

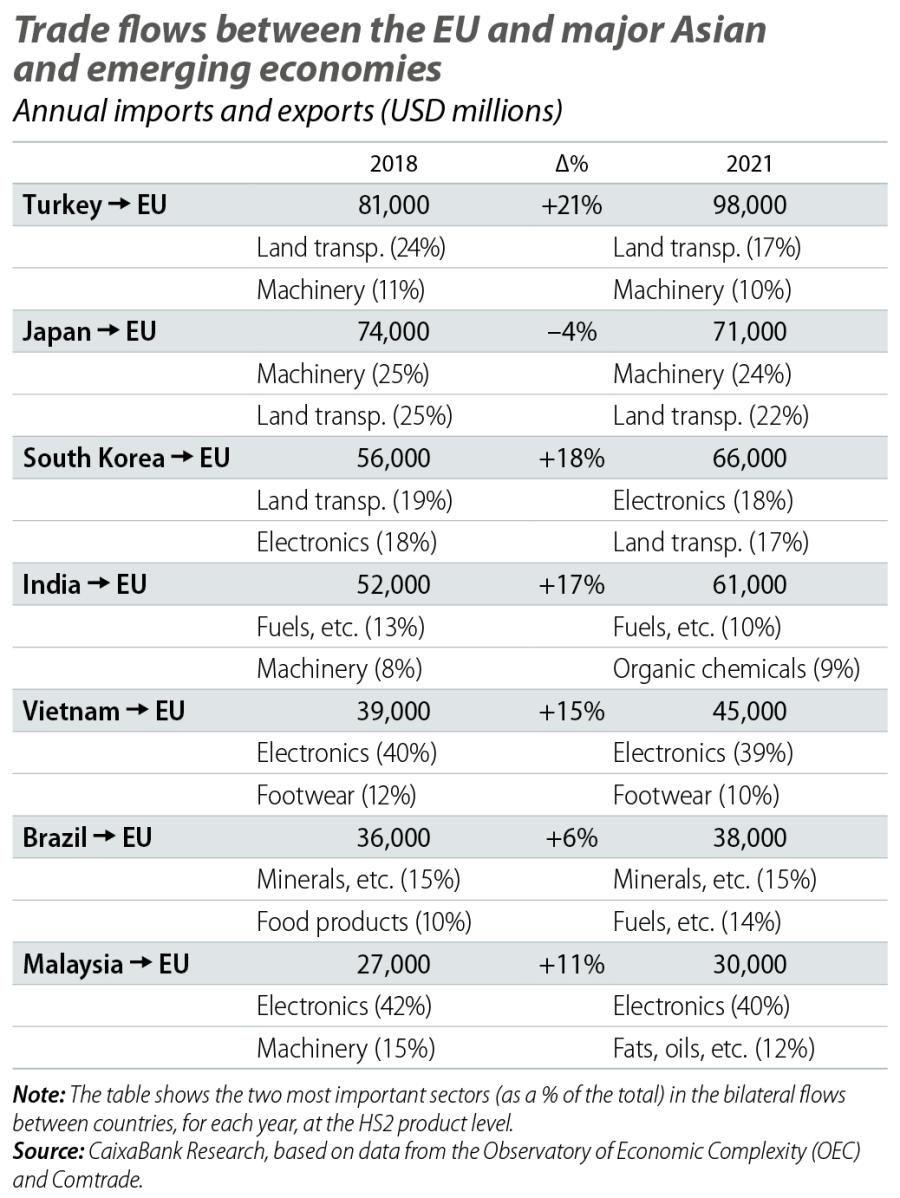

In these same years, not only did the growth of imports from China exceed the growth of imports from the other large emerging and Asian countries (see second table), but the growth of exports from China to these countries increased significantly.2 In other words, the importance of the EU’s direct trade links with China has increased (contrary to what happened between the US and China during the same period), as have the indirect links through other countries due to those countries also having increased their exposure to China.

- 2. Between 2018 and 2021, the increase in exports from China to these countries exceeded 50% in several cases (Turkey, +52%; Vietnam, +68%; Brazil, +50%, and Malaysia, +54%).

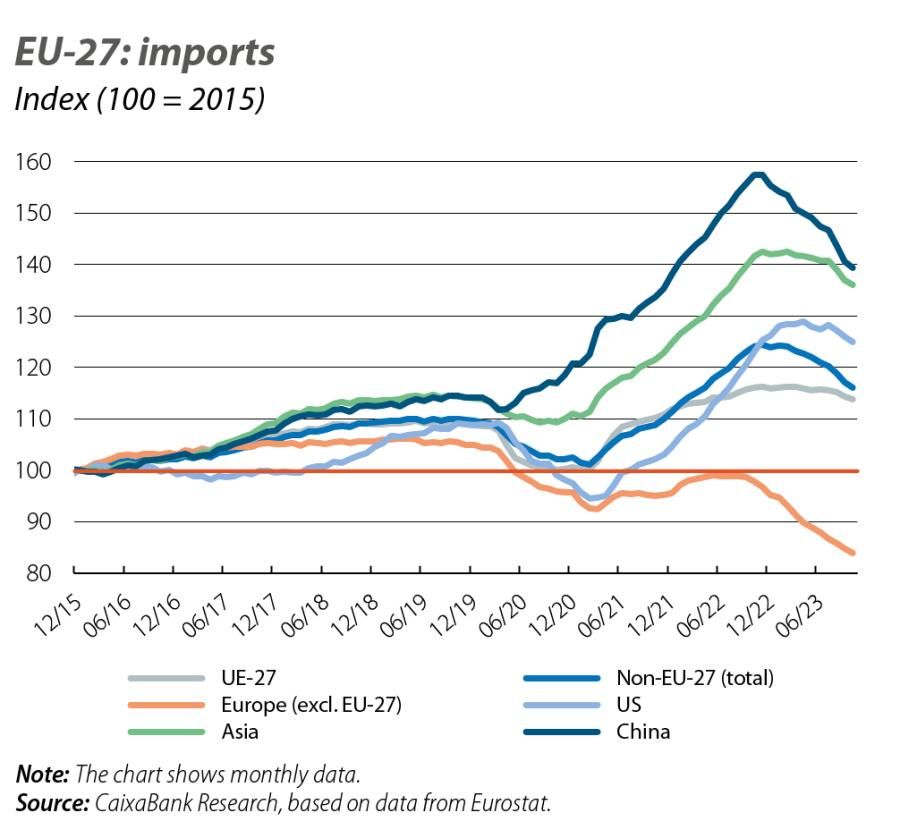

On the other hand, following a period of rapid expansion of European imports during 2022, with more than 40% growth in imports coming from outside the EU (over 30% from China), there are some signs of contraction of direct trade ties between the European bloc and the Asian giant. In 2023, EU imports from China have been falling by more than 10% year-on-year (see chart).3 At the same time, European imports coming from the US have grown by 7%, while those coming from other Asian countries have increased by 3%.4 As a result, since 2021 China has lost 2 pps in its share of the EU’s total external imports, placing its share at 20%, while the share of other Asian countries and the US has increased and intra-EU trade has been strengthened.

- 3. US imports from China have been falling by almost 20% in the same period.

- 4. Of particular note is the growth of European imports from South Korea (+13%), Taiwan (+7%), Japan (+6%) and India (+4%), while imports from ASEAN countries fell slightly (–1%), albeit with differences between countries (from Malaysia, –7%, from Vietnam and Singapore, +3%). As for other regions, of particular note is the growth of imports from the United Arab Emirates (+38%) and Mexico (+12%), and the fall in imports from Russia (–66%) and Norway (–15%).

Two additional trends have also marked recent years. On the one hand, as China has assumed a more prominent role in global value chains, it has also reduced its economic dependence on foreign countries, mainly in terms of goods and services produced in more advanced economies.5 On the other hand, since the end of 2019 China’s main export destination is no longer advanced economies. In fact, in recent years, the Chinese export destinations that have grown the most have been the BRICS countries, the rest of Asia, the Middle East and Africa. For instance, China’s exports to ASEAN countries have grown by 70%, while exports to advanced economies have grown by 20%.

But will the ongoing redesign of trade flows lead to a minimisation of trade risks, whether through direct political intervention or due to fears among businesses of a deterioration in the geopolitical situation that would lead to the use of «economic dependencies» as a diplomatic weapon? Some nuances observed in recent years invite some caution. On the one hand, we have underlined the importance of analysing indirect trade (and investment) ties between blocs, or the so-called «back doors».6 Moreover, given the magnitude of the trade flow deviations observed in recent years and the upturn in uncertainty surrounding trade, we may see an increase in the complexity of global value chains in the coming years, driven by geopolitical considerations. This would likely result in greater opacity – and reduced efficiency – in production processes, as well as in real economic dependencies between blocs.

Whether de-risking turns out to be the end result of this reallocation of resources or not, we may be entering a new era of (de-)globalisation «with Chinese characteristics».7 At the moment, there is a redefinition of the balance towards a global economy that is more dominated by geopolitical concerns, with states playing a more active role through industrial policies and an imminent redefinition of trade policies and of the free trade consensus built in the post-war period. In the first phase of this process, we have witnessed a dominance of «defensive» trade policies, resulting in increased tariffs as well as non-tariff barriers, such as export restrictions or investment control mechanisms. In order to ensure that this process does not lead to a costly and disorderly fragmentation between blocs, it is essential to consider so-called «offensive» trade policies8 and that a detailed understanding of global value chains is achieved. The EU appears to be taking some encouraging steps in this regard, as evidenced by the recent discussion (based on a more pragmatic view of value chains) around critical technologies and progress in trade agreements with countries such as New Zealand, Chile, Kenya, Mexico and India. No less important in this process will be the construction of effective channels for dialogue between the various blocs: the US, China and, in an increasingly multi-polar world, all the rest.

- 5. See the Focus «EU and China: mapping out a strategic interdependence II» in the MR01/2023.

- 6. For a recent and detailed analysis, see, for example, L. Alfaro and

D. Chor (2023). «Global Supply Chains: The Looming ‘Great Reallocation’», Working Paper 31,661, NBER Working Paper Series, NBER. - 7. After years of leadership under Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping was one of the great reformist leaders who has modernised China’s economy, beginning in the 1980s, and has brought the country into a new era of globalisation. One of the fundamental ideas introduced by Xiaoping was the concept of «socialism with Chinese characteristics», which aimed

to redefine the balance between a state-dominated economy and the capitalist world to which it was opening up. In the following decades, China became the world’s second largest economy and the biggest exporter of goods globally, and was the single biggest driver of the latest wave of globalisation. - 8. «Defensive» trade policies, such as tariffs, quotas or restrictions on imports or exports, contrast with so-called «offensive» trade policies, such as the establishment of trade and cooperation agreements between countries.