Tariff tensions and reconfiguration of trade flows: impact on Spain

The US’ tariff hikes of between 10 and 20 pps should have a limited impact on the Spanish economy, less than in other advanced economies, but some sectors could be more affected.

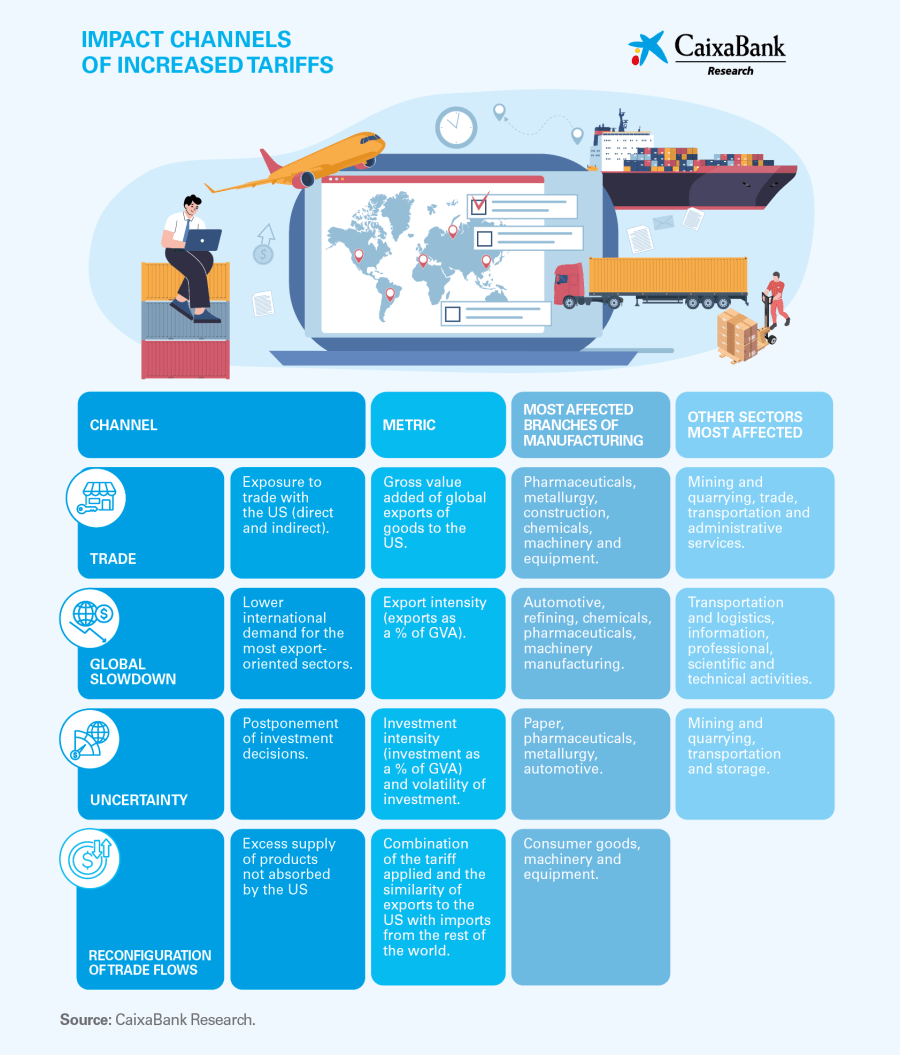

Among the most exposed sectors, we find many of the branches of manufacturing and the mining and quarrying industry, either directly due to their trade links or indirectly due to the increase in uncertainty and weakening global growth. Although less exposed overall, services will also face challenges, especially those that are more export-oriented, capital-intensive or which form part of industrial value chains. The US’ protectionist shift will have significant repercussions for the global economy, as the IMF warned in its latest World Economic Outlook report. Although the impact on the Spanish economy is estimated to be contained and much lower than in other advanced economies, some economic sectors could be more affected. In this article, we analyse the different channels through which an increase in tariffs could impact the various sectors of the Spanish economy, and we assess the possible mitigation strategies that can be implemented.

The measures announced on 2 April by the Trump administration entailed a substantial increase in the effective average tariff applied by the US on Spanish imports following the imposition of a «reciprocal tariff» of 20% on products coming from the EU. However, a week later, this decision was suspended for 90 days, during which period a universal tariff of 10% has been applied to all countries with the exception of China, in addition to the 25% previously in force on steel, aluminium and the automotive sector. In any event, the outlook for tariffs remains highly uncertain, so the final impact is difficult to estimate, as it not only depends on the tariffs that are finally imposed on the EU, but also those imposed on other countries and the countermeasures that the countries concerned may take in response.6 Moreover, the evolution of key economic variables, such as the exchange rate and the elasticity of demand from US importers to the tariff hikes, will also be decisive for the final impact on trade flows.

- 6For example, different reciprocal tariffs that vary from country to country, rather than a universal tariff, can alter relative prices between countries and affect each economy’s final competitive position.

Trade channel: Spain’s exposure to trade with the US is relatively low

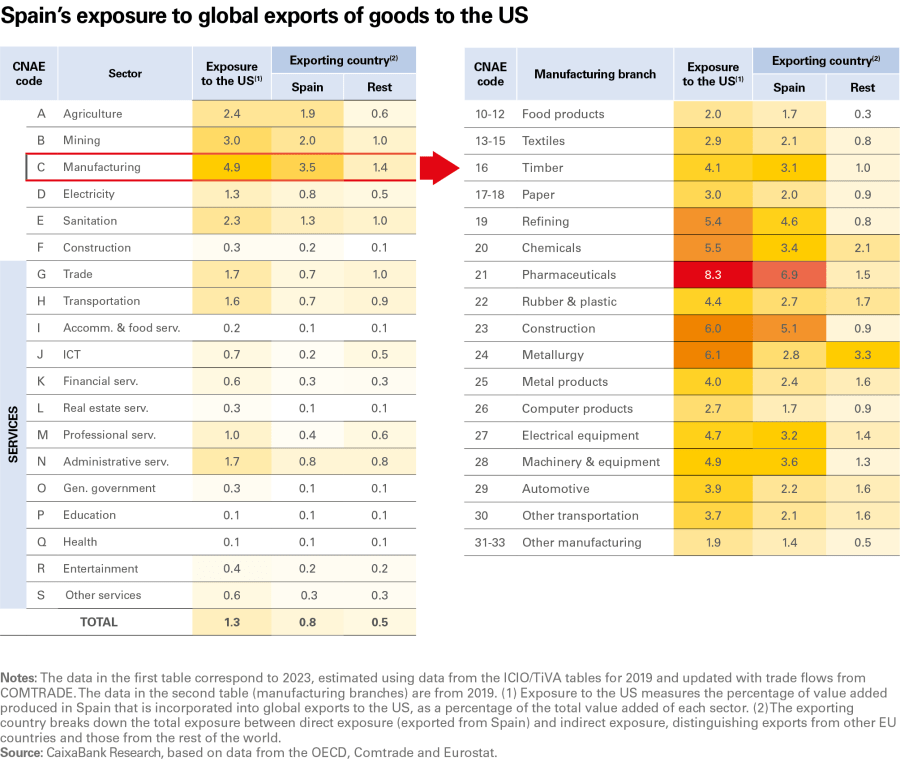

In 2024, exports of Spanish goods to the US represented 1.1% of GDP, compared to 3.2% for the EU.7 If we take into account both direct and indirect exports (i.e. what we export to other countries which in turn ends up being exporting to the US), only 1.3% of the value added generated in Spain ends up being sold in the US (0.8% as direct exports and the remaining 0.5% through exports from other countries to the US).8 Overall, therefore, the Spanish economy’s exposure through the trade channel is relatively low.

- 7Exports of goods to the US accounted for 4.7% of the total exports of Spanish goods. For details of the products exported, see the article «The importance of the trade in goods between Spain and the United States» published in the Monthly Report of December 2024.

- 8Data for 2023, estimated using data from the ICIO/TiVA tables for 2019 and updated with trade flows from COMTRADE. For an explanation of the value-added data, based on the inter-country input-output tables produced by the OECD, see the article «Exposure of the European economy to a US tariff hike: a perspective through values chains», published in the Monthly Report of January 2025.

In addition to the direct effect for firms that export directly to the US, the tariffs also affect other sectors of the economy through global value chains and exports from other countries to the US.

The degree of exposure varies widely from sector to sector, and in some cases it is significantly higher than for the economy as a whole. The table on the following page shows the sectors with the highest percentage of value added generated in Spain that depends on global exports to the US, including:

- Some branches of the manufacturing industry such as the pharmaceutical sector (8.3% of the sector’s value added ends up in the US as its final destination), metallurgy (6.1%), construction (6.0%), chemicals (5.5%) and machinery and equipment (4.9%).

- The mining and quarrying industry also shows significant exposure (3.0%).

- In contrast, agriculture has a relatively low exposure to the US as a whole (2.4% of the sector’s value added), although some products appear to be more exposed, such as olive oil, wine and some canned vegetables.9

- Services generally have a low exposure through the trade channel, although in some cases, such as trade, transportation and administrative services, the exposure is higher than the economy average. These data highlight the complexity of global value chains and the critical role of service activities as providers of the necessary inputs in manufacturing processes.

- 9In 2024, 16.5% of the olive oil that Spain exported went to the United States (the second largest market after Italy). In fact, Spain was the leading source country for US imports of olive oil, at more than 1 billion euros. See «Bilateral Special Report: United States 2024», Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAPA, content available in Spanish).

Finally, the impact of the trade tensions on domestic employment could be significant: 25.3% of employment in Spain depends on final foreign demand, including tourism. Although only 2.2% of employment is linked to final US demand, this percentage is somewhat greater than that of the exposure in terms of value added (1.3%). Again, compared to other countries, the exposure in terms of employment is lower in Spain than in other countries such as Germany or Italy (3.3% of domestic employment depends on final US demand). Within Spain, the differences between sectors are significant: the mining and quarrying industry, manufacturing and agriculture are the most exposed, while services and especially construction have less external dependence.

Indirect channels: global slowdown, uncertainty and financial conditions

In addition to the trade channel, the Spanish economy and its sectors could be affected by several indirect channels that might amplify the initial shock of the tariff hikes. These include, first of all, the deterioration of the global economic outlook, which could affect more export-oriented sectors to a greater extent. Secondly, they include the heightened uncertainty, which often leads to a postponement of business investment decisions, especially in more investment-intensive sectors or those in which investment is more volatile. Thirdly, a tightening of the financial conditions could make it harder for firms to access external financing. Below, we will explain each of these channels.

The slowdown of the main trading partners and the uncertainty will affect the investment decisions and the activity of Spain's productive sectors

Global slowdown

The IMF, in its latest World Economic Outlook report, presented a scenario characterised by increased protectionism, the fragmentation of international trade and geopolitical tensions, which would slow global economic growth. In particular, the entity has revised its global economic growth forecast for 2025 and 2026 in total down by 0.8 pps. Besides the US, for which the growth projection for 2025 has been lowered to 1.8% (revision of –0.9 pps), the other economies hardest hit are Mexico, where GDP is expected to contract by 0.3% (revision of –1.7 pps), and China, with growth of 4.0% forecast (–0.6 pps). For the euro area, the revision is more contained (–0.2 pps), but its economies will show the lowest growth (0.8%), with the exception of Spain, for which it forecasts GDP growth of 2.5% in 2025, in line with the CaixaBank Research scenario.

According to these forecasts, the expected slowdown of Spain’s trading partners is not minor: whereas in October 2024 growth of 1.8% was anticipated for 2025, the latest estimate places it at around 1.4%, representing a downward revision of around 0.4 pps. For 2026, the impact is smaller: going from the 2.0% expected in October 2024 to the 1.7% anticipated in April 2025 (–0.24 pps).10

- 10We apportion the IMF’s GDP growth forecasts for each country according to the relative weight of Spanish exports of goods to each country in 2024.

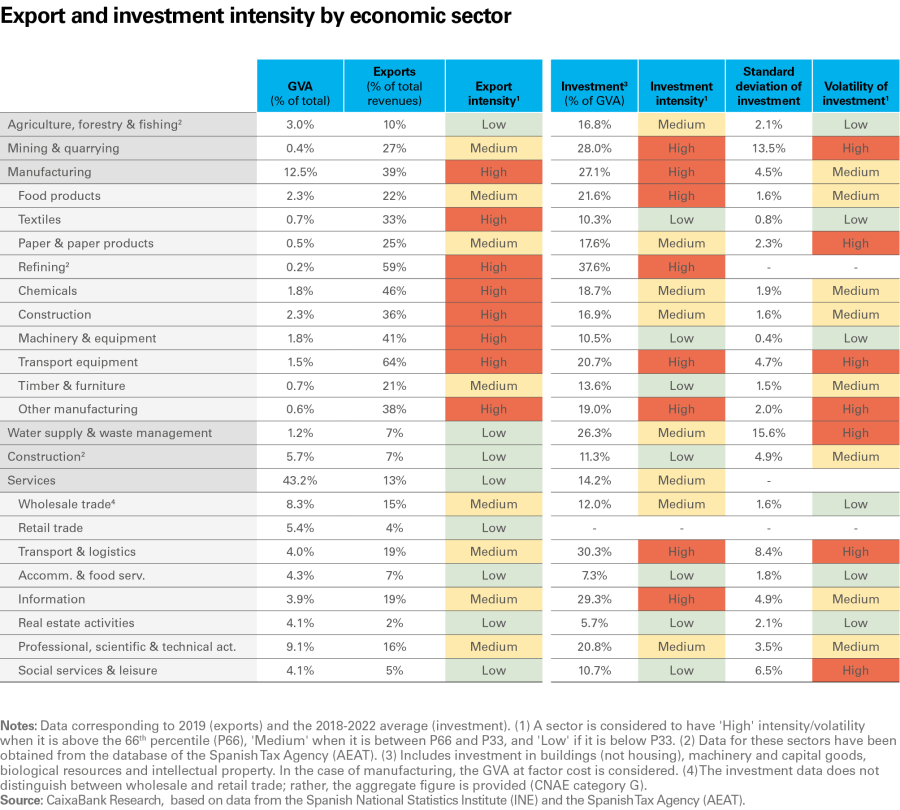

In this environment of lower global growth and slowing trade flows, the sectors that are more open to foreign markets are the ones that could be the hardest hit. The table on the next page shows the export intensity of the various sectors, measured as the percentage of their turnover that comes from sales abroad. The sectors most exposed include some branches of manufacturing, such as the automotive, refining, chemicals and pharmaceutical industries, and machinery and equipment. Within services, although the impact should be more contained due to their lower investment intensity, some of the sectors most exposed are those that in recent years have increased their sales abroad, which include the scientific and technical professional activities, and the information and communications sector.11

- 11See the article «Excellent records in the foreign sector in 2024» published in the Monthly Report of March 2025.

The global slowdown will affect the sectors that are more open to foreign markets, such as some branches of manufacturing, and professional and communications services

Uncertainty and postponement of investment decisions

The increased uncertainty regarding trade policies and, in general, about the new rules of play that will govern international trade can lead companies to adopt a more cautious stance, delaying planned projects and reducing expenditure on capital goods. Consequently, more investment-intensive sectors, or those in which investment is more volatile, are the ones which a priori are likely to be the hardest hit. The table reveals that the paper, pharmaceutical, metallurgy, automotive, and mining and quarrying industries are among the most exposed. On the services side, transportation and storage stand out.

Since the US tariff announcements, volatility in the financial markets has surged. Financial conditions have come under stress, reflecting heightened uncertainty and risk aversion. Although the impact through this channel is very limited for now, we cannot rule out the possibility that the amplifying effects of the shock could end up leading to more stringent conditions for accessing credit, which would affect companies more dependent on external financing.

Reconfiguration of trade flows: risks and opportunities

The increase in tariffs on products imported by the US means that they are now more expensive than the domestic supply within the US market. Given this situation, depending on the level at which the tariffs end up, and considering the change in the cost structure, exporting firms in Spain that want to maintain their share of sales in the US can choose to establish or increase their productive capacity inside the US or, alternatively, somewhere where the tariff treatment ends up being relatively more favourable (e.g. in Canada or Mexico, as preferred US partners under the USMCA).

Spanish firms must adopt different mitigation strategies, either through direct investment in the US in order to sell their products there or by seeking alternative markets

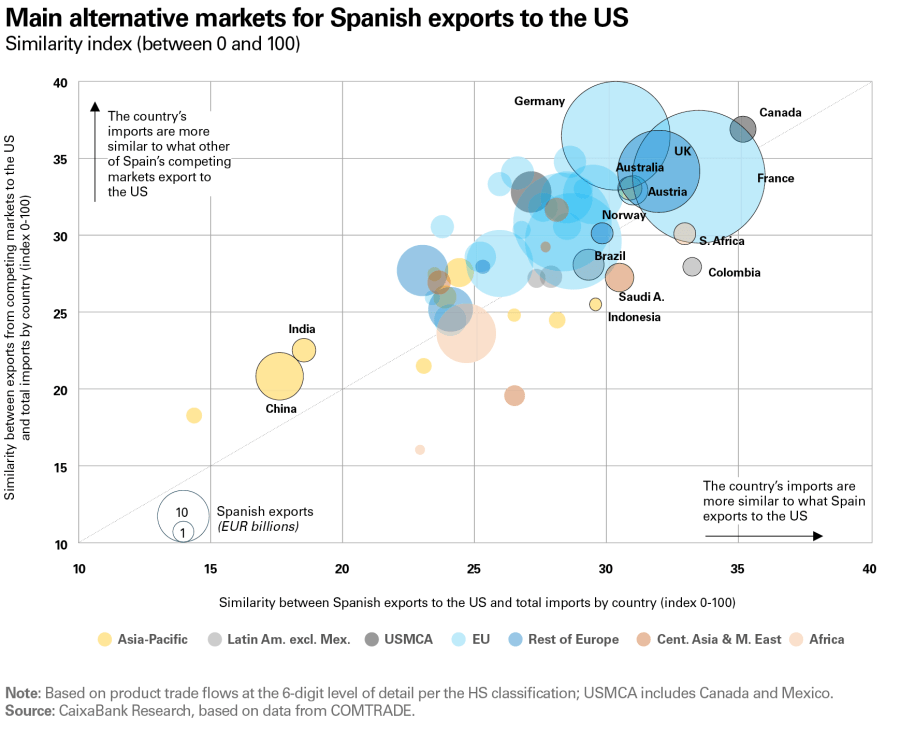

Another option is for exporting firms in Spain to seek to redirect their sales to other foreign markets. The potential for this reconfiguration will depend on a number of factors, including the similarity of demand patterns with respect to the US market, the competition from firms from other countries in a similar situation to the Spanish ones, the volume of the target market and the degree of accessibility in terms of trade to the country in question.

To round off the analysis, we examined how similar Spanish exports to the US are to the total imports from the world’s major markets (see the following bubble chart). To this end, we used a product structure similarity index,12 emphasising the highest values in traditional export markets that are geographically close and of a considerable size, such as Germany, France and the United Kingdom, as well as others in regions with which the EU is deepening its trade relations, such as Canada, Australia and Brazil. On the other hand, two of the major world markets, China and India, have a very different import structure to that of Spanish exports to the US, which limits the ability to redirect trade flows to these countries.

It is also important to note that, in a scenario with higher tariffs to enter the US market, Spanish firms will not be alone seeking alternative destinations and they will need to take into account the greater level of competition from other producing countries. Moreover, as shown by the arrangement of the bubbles along the diagonal line in the chart, it is precisely in these aforementioned markets that demand is more similar to Spain’s exports to the US, and in which competition will also be potentially high. In this regard, the relative positioning of Spanish firms seems to be somewhat more favourable in Colombia, South Africa, Saudi Arabia and Indonesia.

- 12The export similarity index measuring the similarity of trade flows between two countries is produced by taking the sum of the lower value between the two countries of the proportion of the total corresponding trade flow that each product represents. The index ranges from 0 (totally different trade structures) to 1 (identical trade structures). See, for example, its application in: The Fed - The Sectoral Evolution of China’s Trade.

This analysis shows a more varied picture when we use the same similarity index according to product groups (see the following chart). Generally speaking, the structure of Spanish exports of consumer goods, machinery and equipment to the US is more similar to what the rest of the world imports when compared to intermediate industrial goods or agricultural and food products, indicating a greater degree of specialisation within these latter products for the US market.

Among the most similar markets for each product group, a large part of the countries mentioned above appear. Most notably, they include the United Kingdom, which is in the top 5 in three of the four categories; France and Australia, which do so in two of them, as does Austria, and Canada, which leads the machinery and equipment category (including cars). Among the rest, Switzerland is the market that shows the best potential fit with Spain’s agrifood exports to the US, unlike what is indicated by the aggregate similarity index for all products. On the other hand, emerging and developing economies top the list in the case of intermediate industrial goods, although it should be considered that the size of their markets and the current penetration of Spanish exports are relatively limited.

An important factor in the analysis of alternative destinations for Spanish exports to the US is the degree of accessibility to these markets. As an approximation, we take as a point of reference the average tariff applied in each country for products from the EU, differentiating between agricultural and non-agricultural products (see the following chart). Compared to the current level of the universal tariff applied by the US (10%), the tax on European imports is significantly lower in the vast majority of alternative destinations and not only among members of the European Common Market. It would be even more so if the so-called «reciprocal» tariff on EU products announced on 2 April (of 20%), which are currently suspended for 90 days, end up being applied.

The main exceptions to this scenario of lower tariffs compared to the US are found in emerging and developing economies. For instance, Morocco has an average total tariff of 15%, while for Argentina, Egypt, India and Brazil it is around the 10% mark of the US universal tariff. There are also notably higher values in other markets in the case of imports of agricultural products, which are much more protected than other goods in countries such as Turkey, Canada and Norway, with tariffs in excess of 15%. A similar case is that of Switzerland, which we previously mentioned as a market with a potentially attractive agrifood demand for diverting Spanish exports away from the US.

To complement this analysis, it is worth mentioning some additional factors that are relevant for the reconfiguration of trade flows as a result of the US tariff hikes and which once again shows that Spanish exporters are not alone in the search for alternative destinations for their products.

On the one hand, given the greater relative integration of Spain with respect to the common market, close attention will need to be paid to the repositioning of European firms, both through direct investment decisions and through the diversion of trade, which could have an impact on the participation of Spain’s productive sectors in regional EU value chains.

On the other hand, while the US has established a universal tariff of 10% on imports from the rest of the world, the treatment proposed in the announcements of reciprocal tariffs on 2 April would entail a widely varying rate from country to country, with significant changes in relative entry prices into the US market. For instance, exporters in the EU were significantly less penalised than those in South-East Asia, where potential tariffs were proposed in some cases in excess of 40%.

Scenario with a China-US decoupling: how could it affect Spain?

This asymmetry in the tariff treatment is already in force today for products coming from China and we expect this situation will be maintained, given the tendency of the Trump administration to increasingly distance the US economy from that of China (decoupling), even in a scenario with a favourable bilateral negotiation. Under these new conditions, the main potential effects on the rest of the world’s economies include, as was the case in the first phase of the trade war in 2018-2019, the possible rerouting of Chinese exports towards other Southeast Asian countries in order to access the US market. However, the extent of this factor will depend on whether these countries maintain the current universal tariff of 10% or whether the US adopts a tougher position on the rules of origin for products.

The China-US decoupling could lead to a sharp increase in competition, which would particularly affect the production of consumer goods

In terms of what could affect Spain the most, we find factors with an opposite effect. On the one hand, given the stark difference in the increase in tariffs compared to those imposed on Chinese products, opportunities may well arise to increase Spain’s presence in the US market due to its exports now being relatively cheaper than those coming from China. It should be noted here that the elasticity of demand between imports of different origins is usually greater than that it is between domestic and foreign products. This means that US consumers and firms could end up seeking alternative suppliers if the tariffs on goods from China are high enough to cancel out the current price gap (up to 50% cheaper than imports from the rest of the world for a large number of goods). To assess the potential impact of this factor for Spanish firms, we compared the structure of exports to the US with that of Chinese products in the same market (see the upper bars in the chart on the following page). In general, we estimate that the opportunities would be limited, with the degree of similarity being slightly higher within the machinery, equipment and consumer products group, and probably more contained overall if we were to consider the actual degree of substitution among the characteristics within each product line (reflecting, for example, quality differences).

On the contrary, the establishment of tariffs on Chinese products over and above those imposed on other countries could lead to a significant diversion of these goods to other markets, including to Spain, with the consequent increase in competition for local producers given the aforementioned price differences. To measure these risks, we will now compare the structure of Chinese exports to the US with that of imports from Spain (see the lower bars in the chart). In this case, the values of the similarity indices are significantly higher than those of the opportunity indicator, and they are particularly high in the final product categories, both for consumption and for investment. In this case, it is also important to be aware of the actual differences between goods of the same product, as well as the possibility of the EU responding with further tariffs if it perceives significant risks of a «flood» of Chinese exports in the European market. In any case, in this risk scenario, greater disinflationary pressures in international trade are to be expected.

Final reflections

While a US tariff hike of between 10 and 20 pps should have a limited impact on the Spanish economy, a trade war is not good for anyone and some sectors could be affected through different channels. Some branches of manufacturing, such as the machinery and equipment, metallurgy, chemicals, and mining and quarrying industries, are the ones most directly exposed through the trade channel. Through indirect channels, the automotive sector is one of the most likely to be impacted due to its greater export and investment intensity, as well as some service sectors, especially those with a greater share in industrial value chains, those more open to foreign markets and those that are more investment-intensive, such as transportation and logistics, and information and communications.

In this challenging environment, some opportunities could also arise to redirect exports now subject to higher US entry tariffs. Spanish firms must adopt different mitigation strategies, either through direct investment in this market or by seeking alternative destinations with a similar demand structure. Our analysis shows that the opportunities will be greater for consumer products, machinery and equipment. By region, the most attractive opportunities are found not only in traditional export markets in Europe, but also in other regions with which the EU has been deepening its trade relations in recent years.

These opportunities will not be exempt from a high dose of competition from exporters from the rest of the world that find themselves in a similar situation to Spanish firms, seeking alternative destinations to redirect their sales to the US. Thus, a scenario involving a sudden decoupling between China and the US could lead to a sharp increase in competition for the EU, due to it receiving a barrage of Asian goods originally destined for the US market, thus importing disinflationary pressures and greater challenges for the export sector. In Spain, this risk scenario would particularly affect the production of consumer goods.