The EU’s difficult farewell to Russian energy

Although significant progress has been made in recent years in disconnecting from Russian energy supplies, major challenges remain in order for Europe to have a sustainable, secure and competitive energy system.

On 6 May, the EU presented its roadmap,1 accompanied by a draft bill2 presented on 17 June to end the bloc’s energy dependency on Russian oil, gas and nuclear energy (imports of Russian coal have already been eliminated through sanctions). Since the outbreak of the war in February 2022, through sanctions and the search for more reliable partners, imports of Russian energy have declined significantly, although they still represent an important part of Europe’s energy matrix. The path towards eliminating energy imports from Russia, although gradual, will not be an easy one, nor will it be free of obstacles, and it will require significant coordination efforts by Member States (as was already the case for eliminating the transit of Russian gas through Ukraine in December 2024) in order to build a sustainable, secure and competitive energy system.

From Russian energy to diversification

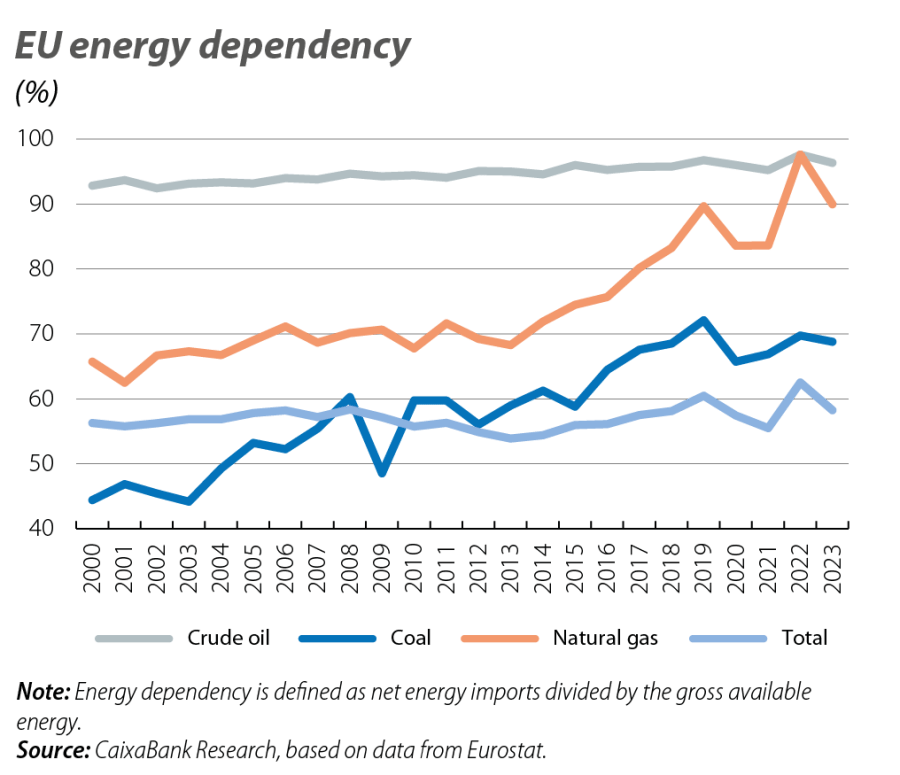

The EU remains heavily dependent on imported energy. In 2023 (the latest available data), the energy dependency ratio3 stood at 58%, a reduction of just over 4 points compared to 2022 and slightly below the 2019 level, albeit still slightly above the average of the period 2000-2019 (when it was below 57%).

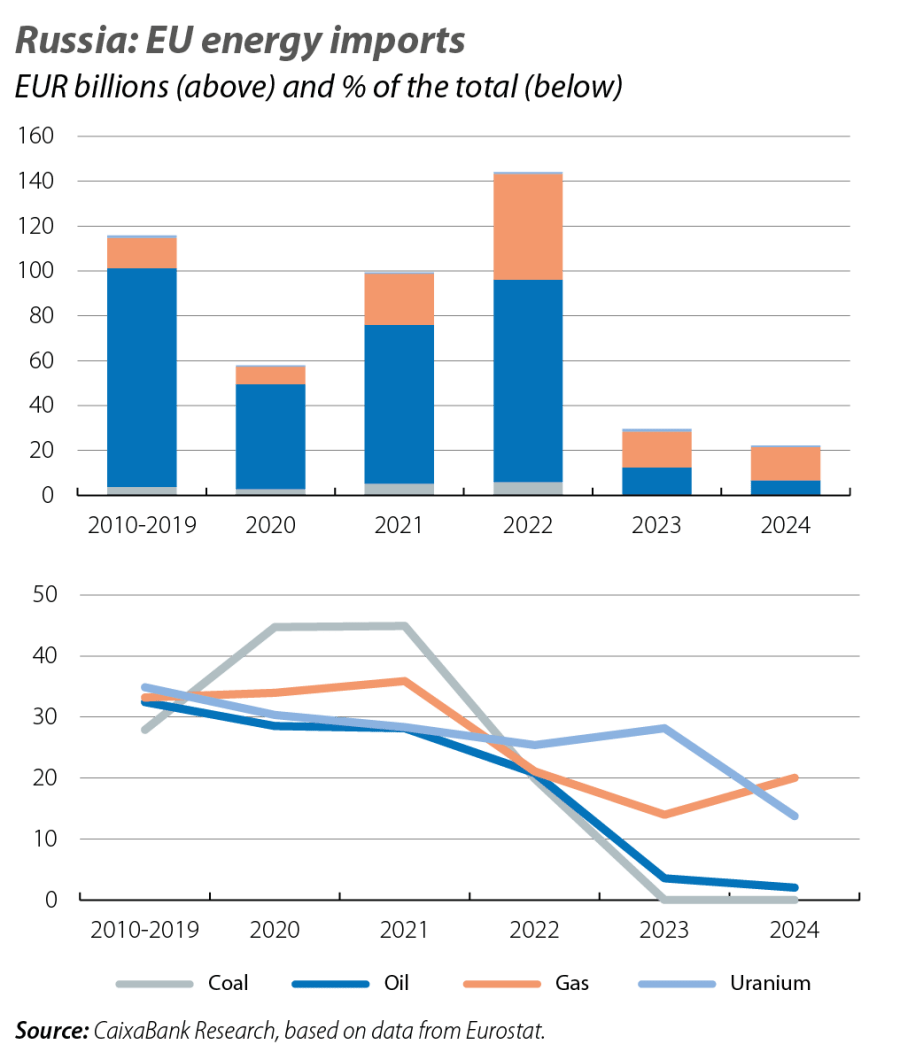

Russian’s invasion of Ukraine highlighted the urgent need to transform the EU’s energy mix. This is a complex task, however, given that at that time Russia was the EU’s leading energy supplier (30% of the EU’s total energy imports in 2021 came from Russia, a figure that has fallen to 5.3% in 2024).4 To this end, in May 2022 the Commission presented the REPowerEU plan (the Recovery and Resilience Facility being its main source of funding). It goals are to save energy, produce clean energy, diversify the EU’s energy supply and intelligently combine investments and reforms.

There is still a long way to go, but progress has already been made on several of these fronts. For instance, imports of Russian oil went from representing around 29% in 2021 to just 2.5% in 2024 (see second chart). The US has become the EU’s main supplier of oil (in 2021, it was the second biggest supplier, below Russia), followed by Norway and Kazakhstan, which have seen their share of the total increase significantly.

- 3The energy dependency ratio shows the proportion of energy that an economy must import. It is defined as net energy imports divided by the gross available energy, expressed as a percentage.

- 4

Calculated using the value of imports in euros, according to the Eurostat database (ds-045409) and taking into account the following products: 2701, 2709, 2710, 271111, 271121, 284410, 284420 and 840130).

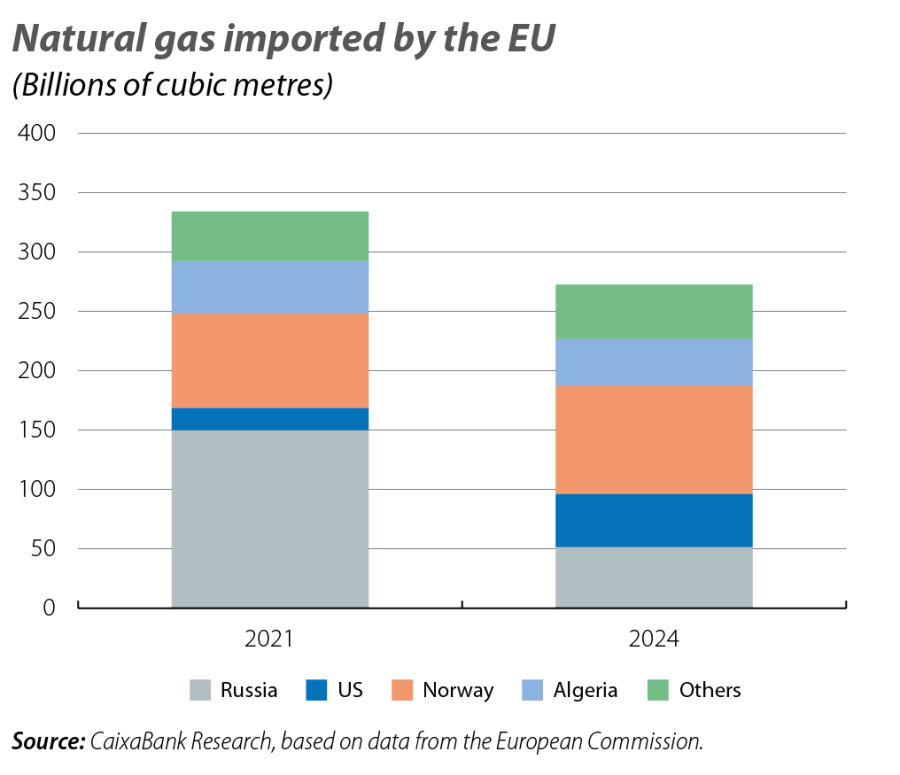

Substantial progress has also been made in the case of natural gas, as the 45% of the EU’s gas imports (whether via pipeline or in the form of liquefied natural gas [LNG]) which came from Russia in 2021 has been reduced to 19% in 2024. Russia has remained the second biggest supplier of LNG, but it is quite far behind the US.

This reduction is mainly explained by the increase in LNG imports from countries such as the US and Norway (which was the main supplier of gas to the EU in 2024, with 33% of the total, particularly via pipeline, since imports of LNG were led by the US). However, the reduction has also been aided by a reduction in gas consumption in the continent (down almost 20% between 2021 and 2024; since 2022, there have been reductions every year, with the exception of 2024, when consumption increased by 1% compared to 2023). The EU has adopted various different measures to ensure its ability to continue importing LNG in the future. Since 2022, the construction and expansion of regasification terminals has been a top priority (e.g. in Germany, which had no LNG terminals prior to 2022, several floating regasification terminals have been quickly brought online). In addition, gas interconnections have been bolstered in order to redistribute gas from ports into the hinterland and long-term contracts are being signed with key suppliers such as the US, Qatar and Algeria. The EU’s storage capacity has also been increased and stockpile levels have been established in order to ensure energy security in the months of peak demand.

Imports of Russian uranium, however, represent an exception to these trends as the reduction has been only limited: in 2024 they remained at practically the same level as in 2022 (a mere 2% below in monetary value, although their share of total European imports has fallen significantly, from 25% in 2022 down to 14%). Although it represents only a small portion of total energy imports, this is an essential product for the operation of nuclear reactors, which generate around 25% of all electricity in the EU. The reduction in imports from Russia has been offset by a significant increase in purchases of Canadian uranium, which in 2024 accounted for 31% of the EU’s total uranium imports, compared to 18% in 2022.

The growing role of renewable energies

Another pillar of the REPowerEU plan was to boost the incorporation of renewable sources in the bloc’s energy production (with the goal of having renewables account for 42.5% of the total energy produced in the EU by 2030). In 2023 (the latest available data), 24.5% of the gross final energy consumption in the EU came from renewable sources, and their share of Europe’s electricity mix has continued to grow, reaching 47.2% of the total net electricity generated in the EU in 2024 (see fourth chart), although there are significant differences from country to country. The leading technologies were wind and hydroelectric power (accounting for over two-thirds of renewable generation), while solar also grew significantly and consolidated its position as a key source for the continent’s energy transition.

The energy disengagement from Russia is underway, but there is still work to be done

Progress is being made in the disengagement from Russia, as well as in the shift in the EU’s energy model. Indeed, significant progress has been achieved in just the last three years: dependence on Russian oil and gas has been drastically reduced, the supply diversified and the transition to renewable sources accelerated. However, major challenges remain, such as the high dependency on energy imports in general, the limited reduction in the case of Russian uranium and the need to strengthen interconnection and storage infrastructures. In this context, the Competitiveness Compass establishes a clear roadmap: moving towards a cleaner, more resilient and affordable energy system will be key not only for energy security, but also for the EU’s long-term industrial competitiveness and economic sustainability. Nevertheless, the EU is starting from a position with competitive disadvantages in the value chain for clean technologies, including aspects ranging from access to critical commodities to the manufacture of batteries and solar panels, where it relies heavily on third-party countries.