Characterisation of the business cycle in the EU: neither widespread, nor robust

The vigorous recovery of the European economy after the pandemic has given way in recent years – in a more hostile geopolitical context – to a situation of weak growth. However, this is not the case across the board, neither geographically nor by sector. In particular, while countries such as Germany and Italy are showing significant apathy, the «European periphery» – so-named in a previous era – continues to show remarkable dynamism, led by Spain and Portugal. A similar contrast is found between the more erratic behaviour of the agricultural, manufacturing and construction sectors – with greater exposure to recent shocks – and the growing role in the economy of skilled services supported by favourable underlying trends such as the digital transformation.

Sectoral divergence: industrial vulnerability and technological boom

The EU as a whole showed highly buoyant activity up until mid-2022, at which point the invasion of Ukraine triggered a negative shock on multiple fronts. Indeed, the consequences of this shock persisted until only a few quarters ago: heightened risk particularly affecting areas bordering the conflict, impact via the trade channel for economies with greater ties to Ukraine and/or Russia, rising costs of energy, agricultural products and inputs as well as construction materials, and the tightening of monetary conditions due to higher inflation.

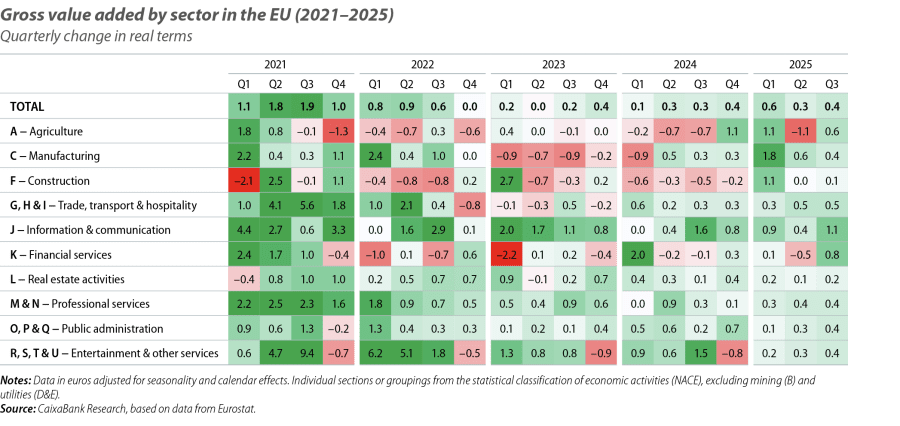

By sector (see first table), the hardest hit were agriculture, also affected by adverse weather conditions; manufacturing, with a contraction led by energy-intensive industry and later affected by trade protectionism; construction, which is sensitive to financing costs and has been emerging from a strong post-pandemic boom; the sector encompassing logistics and hospitality activities, including the negative impact of the conflict on tourism in Eastern Europe;1 and financial services, weighed down by lower credit activity in real terms, in contrast to the nominal improvement in margins.

- 1

See the Focus «European tourism in the post-pandemic era: uneven recovery and new challenges» in the MR10/2025.

In contrast, other sectors less vulnerable to the shock of the conflict in Ukraine have remained buoyant in recent years. The most notable of these are information and communication technology (ICT) services, with annualised growth rates of around 4%; and professional, technical and scientific activities, which include innovation and software development.

Geographical divergence: growth shifts to the «European periphery»

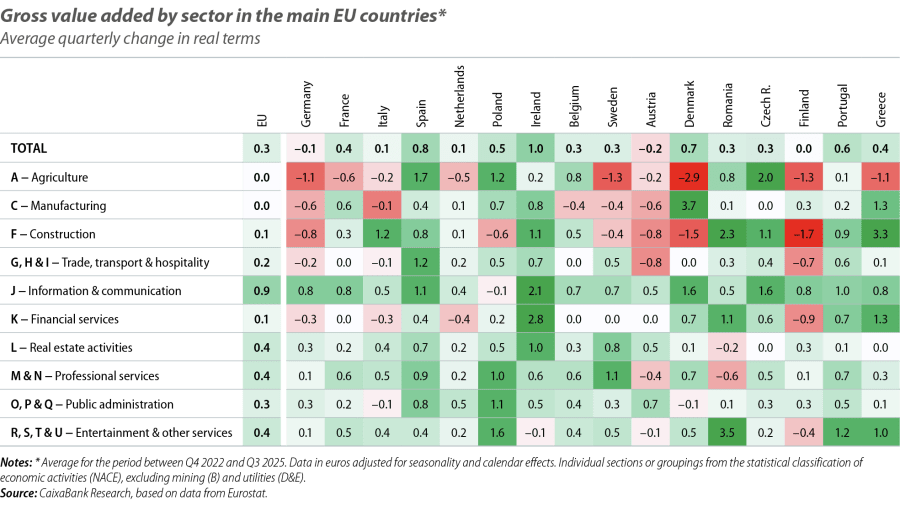

The sectoral divergence of the EU economy can be broadly transferred to the relative behaviour among Member States, although it is worth noting different intensities from country to country (see the second table with data for the 15 largest economies). Taking all sectors into consideration, the countries with the highest growth since the end of 2022 are Ireland, Spain, Denmark and Portugal – with rates that more than double the average progress of the EU. This dynamism contrasts with the slight contraction in Germany and Austria, and the practical stagnation recorded in Italy, the Netherlands and Finland.

In the leading group of countries, of particular note is the cross-sectoral nature of the growth in Spain and Portugal, where all sectors have recorded an increase in value added up to Q3 2025. The economic dynamism also has a broad base in Ireland, albeit with ICT and financial services playing a prominent role, while it is much more concentrated in Denmark, where the pharmaceutical industry and innovation-related activities have had a dominant contribution.2

In the case of the worst-performing economies, the weakness is quite widespread across sectors, especially in Italy and the Netherlands, while in Germany, Austria, and Finland certain activities are showing significant vulnerability to the aforementioned shocks (mainly agriculture, manufacturing, construction, logistics and hospitality). It is worth highlighting the shared exception of ICT services, which even in the cases of Germany and Finland has grown at close to the EU average, as well as the exceptional strength of construction in Italy, which will have been driven by the Superbonus housing renovation support programme.3

- 2

In a situation reminiscent of Nokia's role in the Finnish economy during the nineties, the recent growth in Denmark has been spearheaded by the company Novo Nordisk, which has successfully marketed drugs aimed at combating diabetes and obesity.

- 3

See the Focus «A snapshot of investor apathy in the EU» in the MR05/2025.

Cyclical or structural redrawing of the European economy?

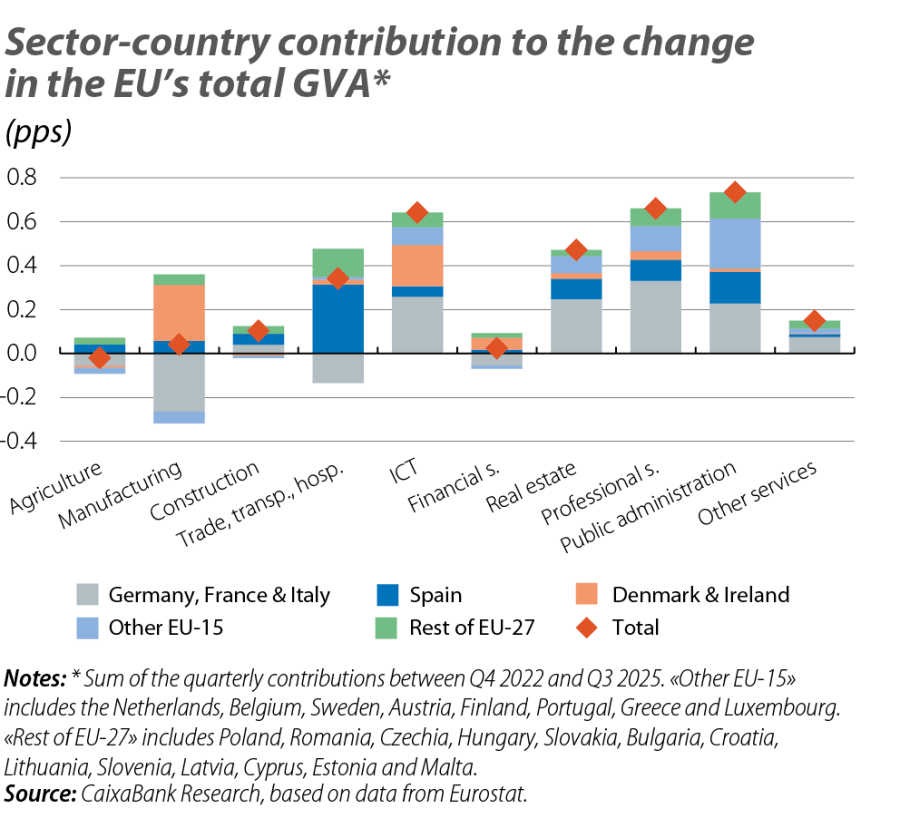

The three largest economies in the EU (Germany, France, and Italy) account for just over 50% of the total value added. However, in the last three years they have been responsible for just 20% of the bloc’s cumulative growth. Furthermore, we find few sectors where their significant role in the economy has translated into a dominant contribution, and some activities have even drained growth from the overall European economy, with the most paradigmatic case being the contraction of Germany’s manufacturing industry (see first chart). On the upside, there are isolated examples, such as the notable contribution of France in ICT and professional services – led by consultancy activities and the digital transformation.

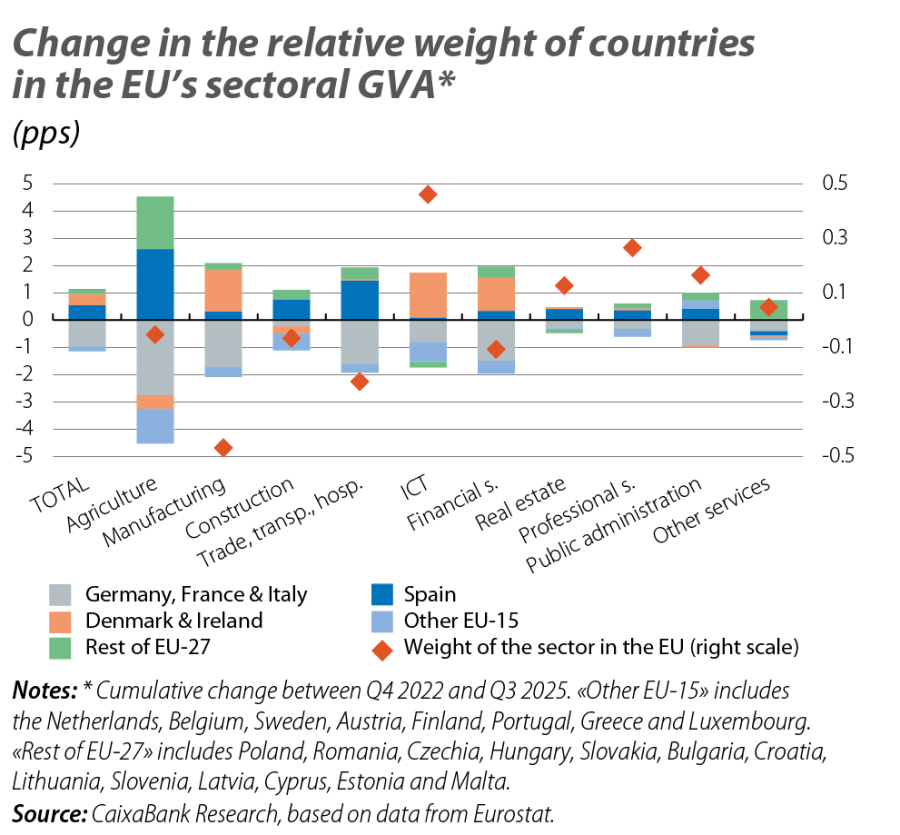

In this way, the EU’s growth engine has a new face in this cycle, and this is transforming the composition of Europe’s productive fabric (see second chart). For instance, we can see how the broad-based dynamism of Spain – which accounts for over a quarter of the total growth of the EU in the last three years – has led to its relative weight increasing by more than half a point, reaching levels not seen since 2010. The growth of Denmark and Ireland re also noteworthy, as they account for almost 20% of Europe’s recent growth (three times more than their relative weight in the economy). As noted earlier, these economies have been supported by specific competitive advantages in certain high-growth sectors, such as ICT services. Finally, the bloc of Eastern European economies is also gaining prominence in the EU – a logical trend as they are expected to converge on the standards of the founding members. Nevertheless, their growth remains restrained and is penalised by their focus on economic activities that show relatively less dynamism, such as agriculture, construction and logistics services.

Therefore, although some of the recent patterns can be read in a cyclical context, the accumulated evidence also points to a somewhat more structural shift in the composition of the European economy. The shift of dynamism towards knowledge-intensive sectors not only reflects a temporary response to the recent shocks, but also embodies underlying transformations linked to technological changes and Europe’s repositioning in global value chains. This evolution, however, is not without risks. Firstly, the concentration of growth in specific activities – such as the pharmaceutical industry in Denmark – poses challenges in terms of resilience and sustainability in the medium term. Secondly, the divergence between countries and sectors threatens to accentuate internal asymmetries if it is not accompanied by policies that improve professional training and strengthen social and territorial cohesion. And thirdly, it is foreseeable that these challenges will intensify as strategic sectors are prioritised, given that their investments largely depend on public impetus in a context of increasing fiscal frictions.4

- 4

See the article «Europe’s medium-term fiscal dilemma» in the Dossier of the MR11/2025.