The transformation of the Spanish labour market: an industry-based perspective

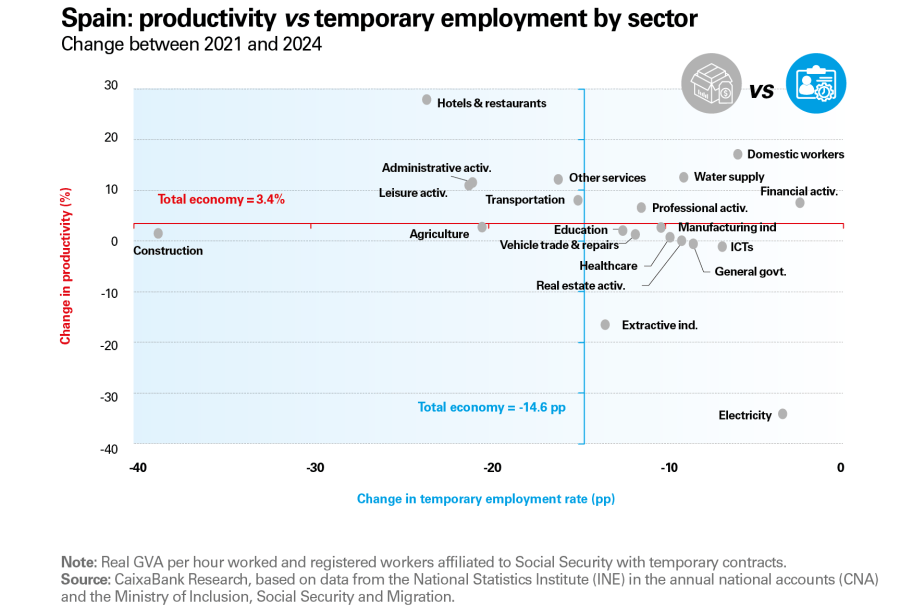

The resilience of the Spanish economy in recent years has been underpinned by both quantitative (strong job creation) and qualitative (more stable employment) improvements in the labour market. Firstly, there has been a fall in temporary employment, a factor that has traditionally fuelled job insecurity and social inequalities and held back investment in human capital, constraining the economy's growth potential; secondly, in some key sectors of our economy this has been accompanied by an improvement in productivity. However, the incipient improvement in overall productivity that has been observed is not widespread across all sectors.

The reduction of the temporary employment rate has been a key factor in recent labour market trends

It is widely known that the Spanish economy has been surprisingly buoyant in recent years. After returning to pre-pandemic levels of activity in Q2 2022, Spain's average GDP growth has remained above 3.0% year-on-year, a much faster pace than its main euro area partners, and the latest forecasts by CaixaBank Research place it at 2.9% for 2025.

One of the cornerstones underpinning the Spanish economy's outstanding performance is the strength of its labour market, which has not only reached record-high employment figures, but has also seen a notable reduction in its high rate of temporary employment: of all registered workers affiliated to Social Security in October, 12.1% were temporary, less than half the 28.1% recorded in the same month of 2021. This has been thanks to the labour reform passed in December 2021,6 which introduced restrictions on the use of temporary contracts, while promoting permanent intermittent contracts to cater for seasonal but recurring work.7

- 6

See the article «Employment stability improves in Spain», in the Monthly Report published in February 2025.

- 7

These contracts have become more prevalent in all sectors, but especially in agriculture, construction and services (especially hotels and restaurants and leisure activities). For further information, see the article «Where has the fall in the temporary employment rate been concentrated?» in the Monthly Report published in June 2025.

The temporary employment rate has been reduced throughout the production sector, but not equally across all sectors

Although the reduction in temporary employment has been broad-based, there are significant differences between sectors and industries, with the sharpest reductions being seen in sectors that started out with the highest rates before the labour reform, such as construction, agriculture and, within services, hotels and restaurants, leisure and administrative activities.8

- 8

This includes rental activities, employment-related activities (temporary employment agencies), security and investigation activities, building services and cleaning and gardening activities, travel agencies and tour operators, etc.

…and, at the same time, there are early signs of improvement in productivity

In the period under analysis, the economy's overall productivity has improved, but this increase has been volatile and is still insufficient to narrow the gap with the euro area: between Q2 2022 and Q3 2025, GDP growth per hour worked averaged 0.9% year-on-year, compared to 0.5% in the 2014-2019 period.

Hourly productivity grew by twice as much between 2022 and 2025 as in the pre-pandemic period

Our sector-based analysis9 (see the chart below) shows that the change in productivity has not been uniform and improvements vary significantly depending on the characteristics of each activity. Thus, some sectors have experienced sharp reductions in temporary employment, accompanied by strong productivity gains (e.g. hotels and restaurants), while others have drastically reduced temporary employment without an equivalent surge in productivity (e.g. agriculture and construction). It should be noted that while lower temporary employment may benefit productivity in the long term by improving job stability and training, its direct impact in the short term is difficult to quantify due to cyclical factors, such as the post-pandemic recovery, digitisation and global energy shocks.

- 9

We use annual national accounts (CNA) figures, as they provide a more detailed breakdown by sector than the quarterly national accounts of Spain (CNTR), and we compare 2021 –immediately before the labour reform– with 2024.

As mentioned above, among the sectors that have seen the greatest reduction in temporary employment, hotels and restaurants stand out. This sector has also seen the highest increase in productivity of all activities analysed (by almost 28.0%). However, it is likely that these extraordinary figures have more to do with the de-seasonalisation of the sector and the sharp increase in demand after the pandemic, especially the upswing in tourism (we must recall that the hotel industry was one of the sectors that was hardest hit by the social distancing measures introduced to contain the spread of COVID-19). In contrast, workforce numbers did not recover as quickly, and structural changes introduced in the sector (digital services and new practices such as QR menus, in-app orders, etc.) allow services to be provided with fewer staff. Leisure activities are in a similar situation to hotels and restaurants, with a notable increase in productivity following the reopening of theatres, cinemas, concerts, sporting events with audiences, etc.

The increase in productivity has not been uniform across sectors: the extraordinary rise seen in hotels and restaurants contrasts with the stagnation in agriculture and construction

In contrast, construction and agriculture now have a more stable workforce, but their productivity remains relatively low and has hardly improved. The limited productivity gains in construction are due to the sharp rise in employment after the pandemic (it is a very labour-intensive sector, hence the relatively small technological improvements), coupled with some efficiency problems it has had to face, stemming from the shortage of skilled labour in some segments or the rising cost of materials. There are several factors behind the lower productivity in agriculture. Firstly, the sector was one of the least hard hit by the pandemic crisis and much of its production had already recovered by 2021, so it did not experience as sharp an upswing as other industries. Secondly, in 2022-2023, the Spanish agricultural sector was hit by very adverse conditions, due to the drought and the consequences of the sharp rise in the price of certain inputs such as fertilisers and fuel, which limited production gains and kept costs very high.

At the other end of the spectrum, the sectors with the smallest reductions in temporary employment are electricity and financial activities, but this is because they had low rates to begin with, the lowest of all sectors: below 5.0%. As for productivity, in both cases it remains among the highest across all sectors, but they are following very different trends. In the case of electricity, productivity plummeted by 34.0% in the period under analysis, affected by

(i) fluctuations in energy prices; (ii) the energy transition to renewables, which requires capital- and training-intensive investments, reducing operational efficiency in the short term; and (iii) regulatory changes (windfall taxes and price caps), which have hit the profitability and efficiency of the sector. As regards financial activities, the digitisation process that the banking sector has been undergoing for several years, combined with a pick-up in earnings on the back of rising interest rates, further consolidated the productivity gains that had previously been recorded.

In any event, the improvements in productivity described in this article are in terms of hours, but for the growth to be sustainable in the medium and long term, productivity per worker must also improve, which is not so clearly visible. In this respect, in terms of GDP per employee (full-time equivalent job, FTE), the increase has been very modest, just 0.3% year-on-year on average between Q2 2022 and Q3 2025, the same as in the pre-pandemic period. This means that a large part of the increase in GDP per hour worked is the result of a reduction in the number of hours worked per worker, by 0.7% per year on average over the period under consideration.

Overall, the Spanish economy is shifting towards a more stable and resilient labour model, although the challenge remains to consolidate sustained productivity growth based on improving human capital, innovation and business efficiency.