US 2026 outlook: resilience with frailties

The US economy is facing 2026 with a mix of strength and vulnerability. The resilience demonstrated in 2025 has exceeded expectations, and investment in AI, the fiscal stimulus and new rate cuts predict another year of strong growth. Nevertheless, the picture is not free from risks.

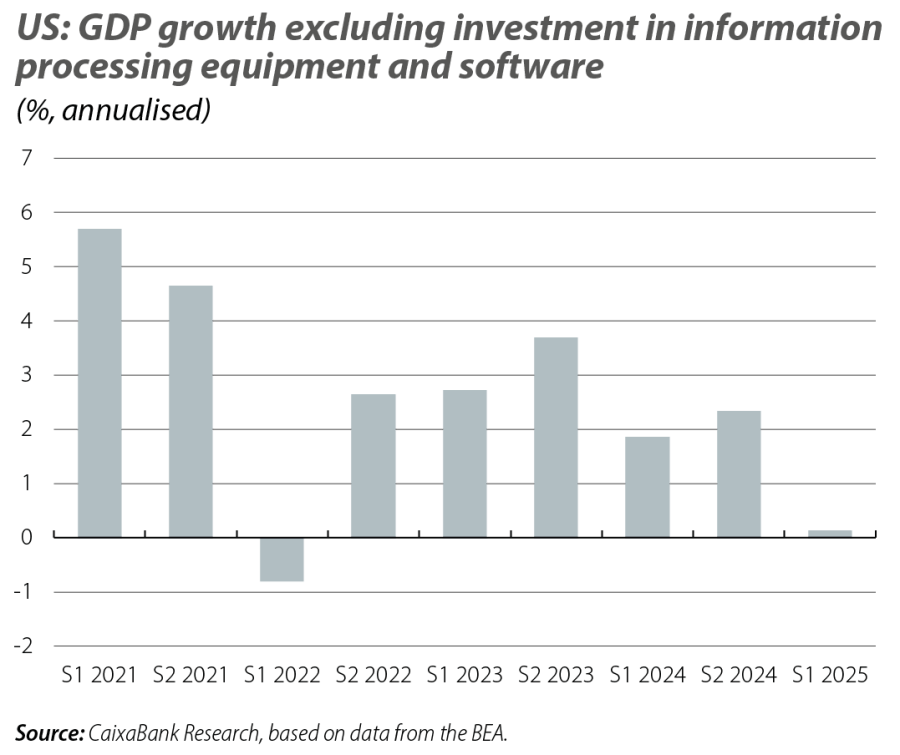

The US economy has shown remarkable resilience in 2025, despite facing a complex environment marked by tensions in trade and domestic policy, as well as uncertainty. In spite of these obstacles, growth reached 1.6% (annualised) in the first half of the year, driven primarily by the dynamism of investment in assets linked to artificial intelligence (AI), as well as by private consumption which, despite a moderation in its growth rate, continues to contribute to economic activity.

Looking ahead to 2026, the outlook is positive. We project a growth rate close to the potential (2%), based mainly on the continuity of the vigorous private investment cycle, particularly linked to AI. Another source of support will be the transition of monetary policy towards a more neutral position, as well as an expansionary fiscal policy that maintains the stimulus in the short term. However, these pillars also carry risks in the medium term, with doubts over the return that the current wave of investment in AI will yield, the health of public accounts and the sustainability of debt, the ability of the Fed to complete the transition to neutrality and the backdrop of risks more directly linked to the measures introduced by the new Trump administration. The latter include the impact on the labour market, wages and economic activity of restrictive migration policies, the reconfiguration of US institutions and persistent tariff tensions.

The surge in investment in AI spearheads growth

In 2025, private investment in technology and AI has been the major driver of growth. Spending on information processing equipment (computers, servers) and software grew in the first half of the year at annual rates of 35% and 23%, respectively, and contributed 1.4 pps to a total growth of 1.6%. Without this push from investment in technology, GDP would hardly have grown at all.

The epicentre of the boom is Silicon Valley, where a small group of large firms1 have invested some 194 billion dollars in infrastructure and data centres in the first half of the year. It is estimated that this figure will reach 368 billion by the end of 2025 (equivalent to 1.2% of GDP) and that it could reach 432 billion in 2026, more than double the amount invested in 2023. In addition, we must consider the large projects being pursued by companies such as OpenAI and the vast investments required to bolster the electricity grid and chip production, where players such as Nvidia stand out.

In the short term, this investment boom has a clearly positive effect on the economy. However, the concentration of growth mainly in a single driving force poses risks. If the technological tailwind weakens, underlying weaknesses could be exposed: more fragile consumption, a labour market that has begun to cool, and the inflationary effects of tariffs which, although limited to date (partly due to the accumulation of inventories and advanced purchases in Q1 2025), could intensify as inventory buffers run out.

In addition, questions have arisen regarding the sustainability of this boom. Companies face operational challenges in scaling their infrastructure, while the true impact of AI on productivity and its ability to generate sustainable benefits remains unclear. If expectations are not met, there could be a correction in stock market valuations in the medium term, the financial implications of which will be more or less broad depending on the rise in credit and debt that accompanies the investment boom in the coming years.2 Another possible amplification factor lies in the rise of more leveraged and circular financing structures, with cross-holdings between companies within the same sector along value chains.

- 1

In particular, we refer to Amazon, Microsoft, Meta, Alphabet, Oracle, Apple and Tesla.

- 2

For example, according to estimates by Morgan Stanley and Bloomberg, of the investments that the big tech firms will make between 2026 and 2028 in data centres, 50% will be financed with these companies’ own cash flows, 30% with private credit and the remaining 20% from other sources. See S. Ren (2025, 2 October), «AI Data Centers Give Private Credit Its Mojo Back», Bloomberg.

The monetary lever

On the monetary front, the Federal Reserve is in the midst of a transition from a position it qualifies as moderately restrictive to a more neutral one. Currently, the fed funds rate lies in the 3.75%–4.00% range and we expect it to fall to 3.00%–3.25% by the end of 2026. This shift responds to a deterioration in the labour market: job creation has cooled, recruitment is declining and unemployment has begun to creep up. Although inflation remains above the 2% target, the Fed is seeking to avoid an excessive cooling of employment which could compromise economic activity.

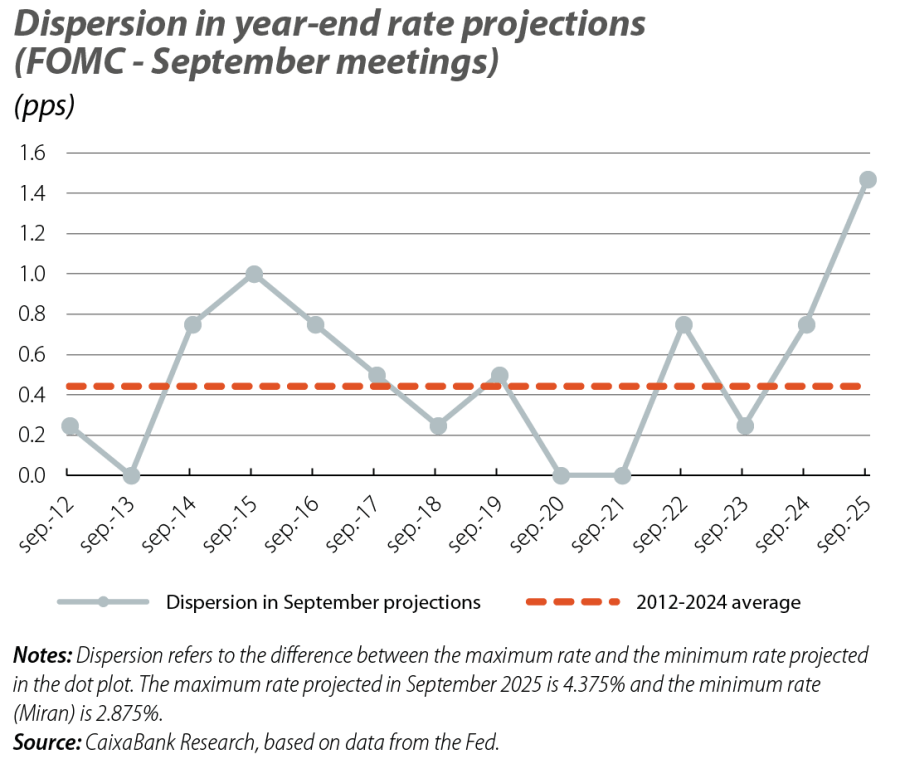

However, consensus within the FOMC is limited: one group of members is advocating a degree of prudence while another is pushing for more aggressive cuts. In a context in which the two mandates – price stability and full employment – are pulling in opposite directions, the margin for error is narrow and the path of interest rates is uncertain. In Powell’s words, the next cuts are «far from» guaranteed.

In addition to this uncertainty there is an institutional risk. In 2025, the White House intensified its pressure on the Fed, proposing appointments of allies and sparking debate over the central bank’s independence. The attempt to oust Governor Lisa Cook set an unusual precedent, and the appointment of Stephen Miran – an economist close to President Trump – aroused misgivings. Miran has expressed divergent positions to the rest of the FOMC, contributing to the widest dispersion of interest rate projections among Fed members at its September meeting (when there is usually greater consensus on the rates anticipated for the end of the year) in the last 13 years, as seen in the second chart. While we see no clear signs that the Fed will lose its independence, and we are confident that the majority of its members will continue to act to fulfil its mandates, this type of institutional tension adds uncertainty to the economic and financial environment. Moreover, this comes at a time when at least two Board seats are up for renewal in 2026.3

- 3

In January, Miran's position is up for renewal, after he took over to finish Adriana Kugler’s term in September 2025. Powell’s term as chair of the FOMC expires in May and, although his position as a governor is not due to end until 2028, his predecessors have resigned from the board after the end of their term as chair.

Fiscal outlook

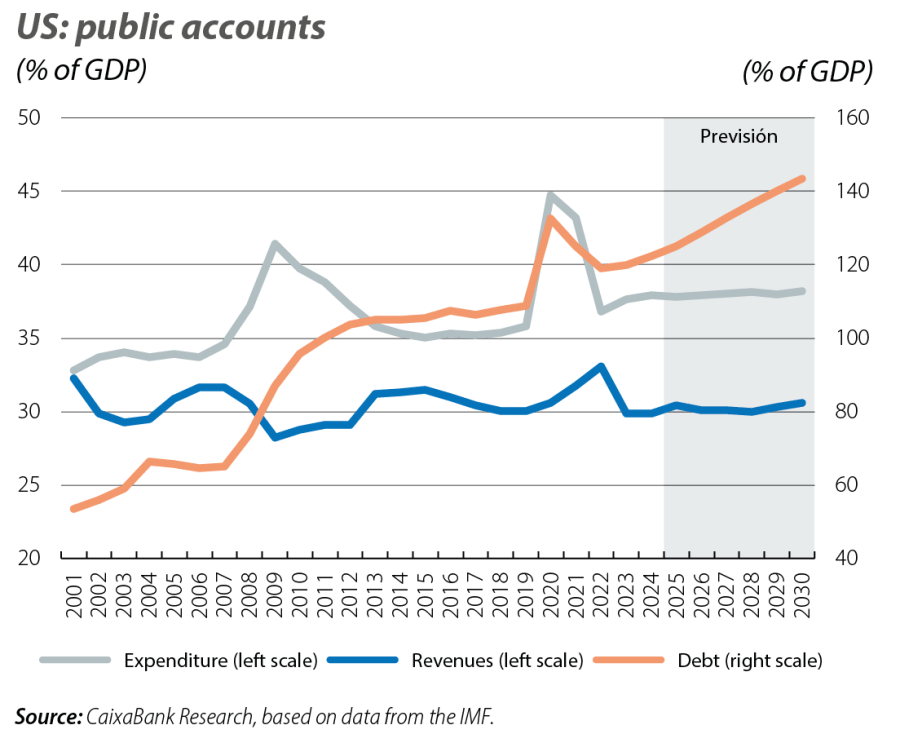

In July 2025, the OBBBA (One Big Beautiful Bill Act) came into force, making most of the tax cuts that were passed in 2017 permanent and adding some new temporary cuts.4 It also allows companies to immediately deduct certain capital expenses, thus encouraging short-term investment.

These measures help sustain growth in the short term, but at the cost of further deterioration in the public accounts. Thus, all the indicators suggest that this year the public deficit will remain at around 7% of GDP – double the average prior to the pandemic – and the forecasts indicate that it will remain at that level for several years. The increase in revenues from tariffs is unlikely to offset the projected increase in public spending. The IMF estimates that, if this trend continues, gross public debt could exceed 140% of GDP by the end of the decade, a very significant increase in a short period of time considering it expects it to close this year at 122%. In other words, today’s fiscal momentum could become a burden tomorrow.

- 4

Such as the exemption from income tax for tips and overtime.

Cautious optimism

Overall, the US economy is facing 2026 with a mix of strength and vulnerability. The resilience demonstrated in 2025 has exceeded expectations, and the two growth drivers – AI investment and new rate cuts – predict another year of strong growth. However, the picture is not free from risks. The tech boom could well be prolonged and, if the productivity gains materialise, its benefits will extend beyond 2026. However, if the return on these investments falls short of expectations, then the negative impact on growth and on financial markets would be significant in the medium term. The Fed faces internal dilemmas and external pressures while labour, tariff and political risks persist, and all this against the backdrop of a deterioration of the public accounts.