There are reasons why housing has become the top concern among European citizens

This analysis examines the recent evolution of the European residential market and explores differences between countries in a context where housing has become the main concern among Europeans. What we see is a cycle marked by successive shocks and an insufficient supply, which is now emerging as the main source of tension.

On 16 December, the Commission sent the so-called European Affordable Housing Plan to the European Council and Parliament, which aims to facilitate Europeans’ access to housing with adequate living conditions.1 The plan sets out a series of measures aimed at boosting the housing supply (particularly in areas with the greatest deficit), attracting investment and mobilising funding, supporting the most vulnerable segments – such as young people and low-income workers – and reviewing regulations in order to avoid bottlenecks in the provision of housing and improve affordability in the medium term. This analysis examines the recent evolution of the European residential market and explores differences between countries in a context where housing has become the top concern among Europeans.2

Supply shortages take over from recent shocks in the current European housing market phase

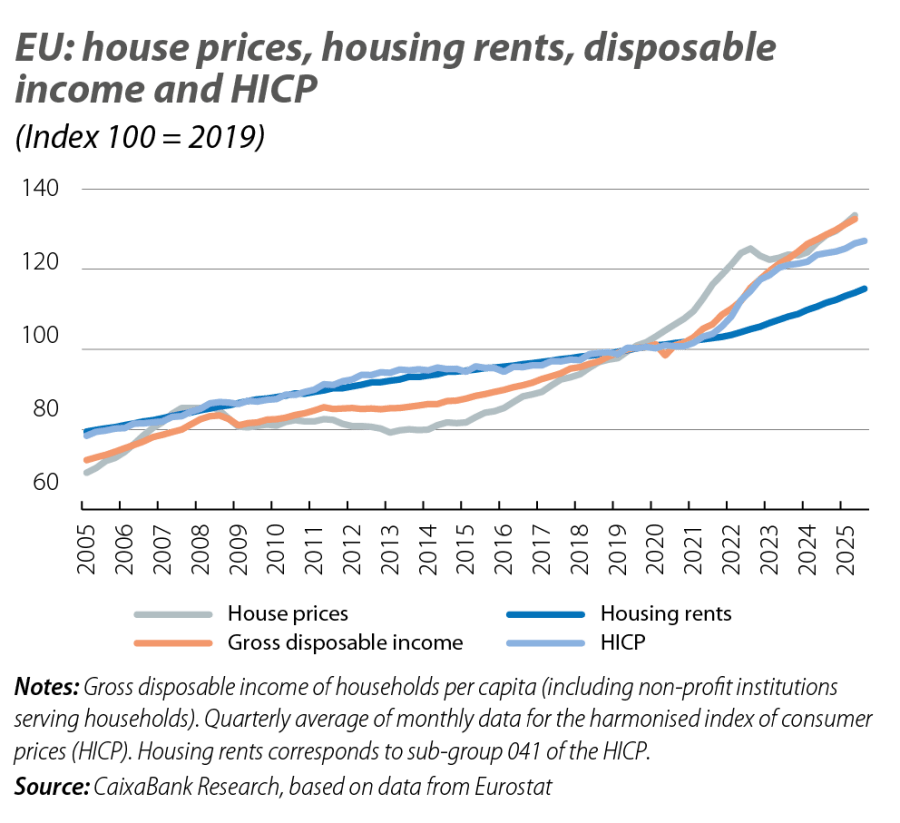

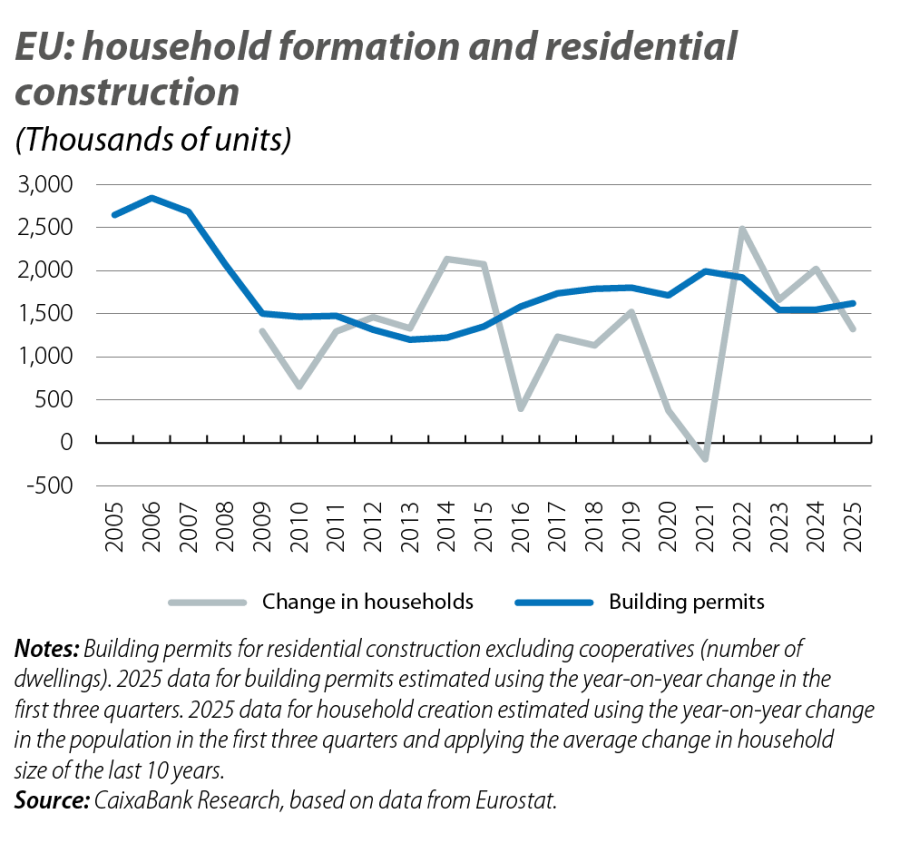

The residential real estate cycle in the EU over the last 10 years has been characterised by four distinct phases. An initial phase is framed by the emergence from the financial-sovereign crises, extending from 2014 to 2019, just before COVID-19. During this phase, average house prices in the EU grew at an annual rate of around 5%, far outpacing consumer inflation and rental costs (just over 1% in both cases), as well as gross disposable income per capita (3%) (see first chart).3 This rapid price growth reflects both an adjustment in real terms, following the sharp corrections that occurred between 2007 and 2013, and a slow initial response from supply to the increase in the number of households (see second chart).

- 3

House prices are based on sale transactions. Rental costs are approximated by taking sub-group 041 of the harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP), which reflects both updated existing contracts and new rental agreements.

A second phase occurs in the context of the pandemic, where there was an unusual accumulation of savings, resulting from the job retention schemes that contained the fall in labour income, combined with lower spending due to the mobility restrictions and interruptions in the supply of certain products.4 As the situation began to normalise, investment in housing – and not only in the primary residence segment – increased significantly. This pushed up purchase prices, which doubled their year-on-year growth rate to 10% by the end of 2021 and the beginning of 2022, far exceeding the growth of incomes, prices and rents.

A third phase is triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which gave rise to an energy and price shock that initiated a more restrictive monetary policy cycle. The ECB’s rate hikes and the consequent rise in bank financing costs cooled the European housing market, resulting in the relative stagnation of residential property prices from mid-2022 up until the start of 2024, once monetary policy had fully passed through to the real economy. This situation contrasts with the sharp growth in consumer prices during this period (in excess of 10% year-on-year in some months) and the acceleration in the increase of rents, which doubled their growth rate to 3%.

Finally, in the last two years, we find ourselves in a different phase in which the supply of new housing has barely recovered from the lows of 2023-2024, hampered by bottlenecks, labour shortages and rising construction material costs. In contrast, demand has accelerated in a context of monetary policy easing5 and increased demographic growth driven by immigration – partly due to the arrival of Ukrainian refugees, partly due to the attraction of workers in response to labour shortages in some sectors. Thus, purchase prices are once again on the rise, at a rate around 5% year-on-year, in line with the average growth of disposable income across the EU, while rental costs are also now outpacing consumer prices (slightly above 3% vs. 2.5%, respectively).

- 4

See «Savings and consumption in times of pandemic: a historical and international review» in the MR11/2021.

- 5

See «House prices in Europe reactivate with the shift in monetary policy» in the Real Estate Sector Report for S1 2025.

Marked geographical heterogeneity among Europe’s residential markets

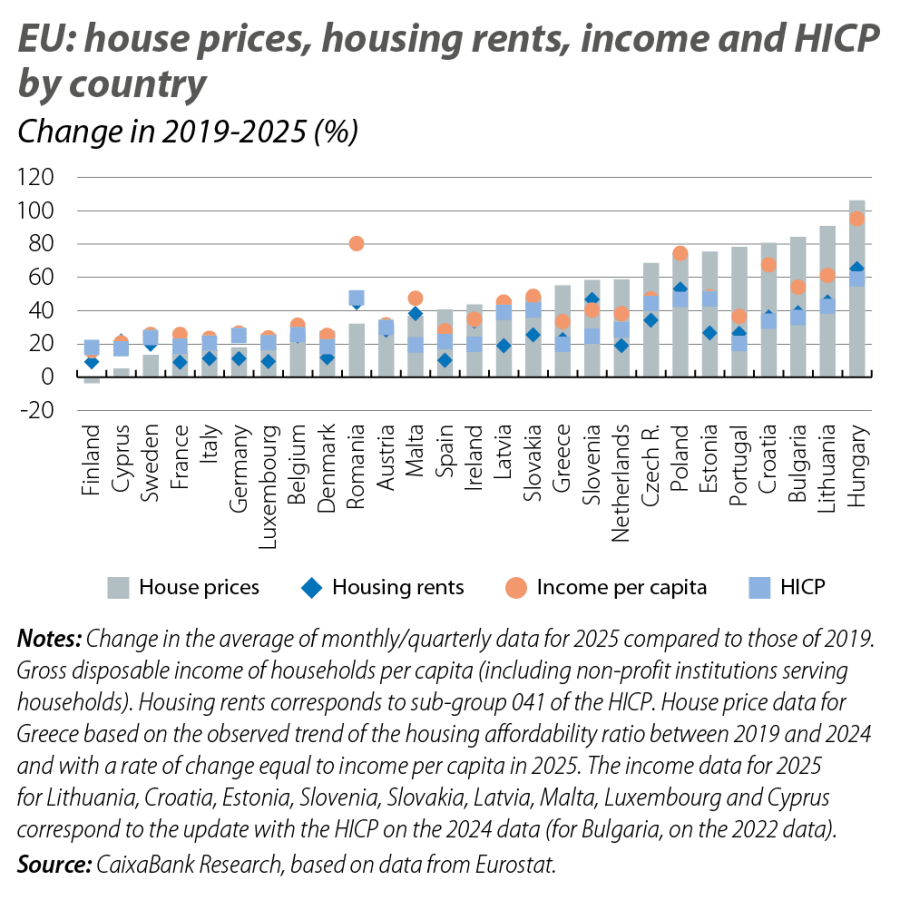

In recent years, house prices in the EU have shown differential behaviour from country to country, although a certain geographical pattern emerges, with the sharpest increases recorded throughout Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean region (with Greece and Portugal leading), while the central-northern region has shown more contained growth, with the exceptions of Ireland and the Netherlands (see third chart).6

- 6

ECB (2025). «Developments in the recent euro area house price cycle».

Even within these groups, it is possible to distinguish Member States based on how aligned the evolution of house prices has been with the headline price index (change in real prices), disposable income (as a measure of affordability), or rental costs (a proxy for yield or opportunity cost). Thus, for example, purchase prices in Poland, Croatia, Portugal and Bulgaria have increased by around 80% between 2019 and 2025, but whereas in the first two cases the growth in per capita income has been similar, in the latter two the accumulated gap is 30-40 pps, resulting in a significant deterioration in the affordability of home ownership for their populations. Similarly, Spain and Ireland have recorded price increases of around 40%, some 10 pps above the increase in household incomes, although the difference between them is marked by the behaviour of rental costs, which have been much more contained in the former case (10% vs. 30%) as a result of the measures applied during COVID-19 and the subsequent controls in stressed areas.7

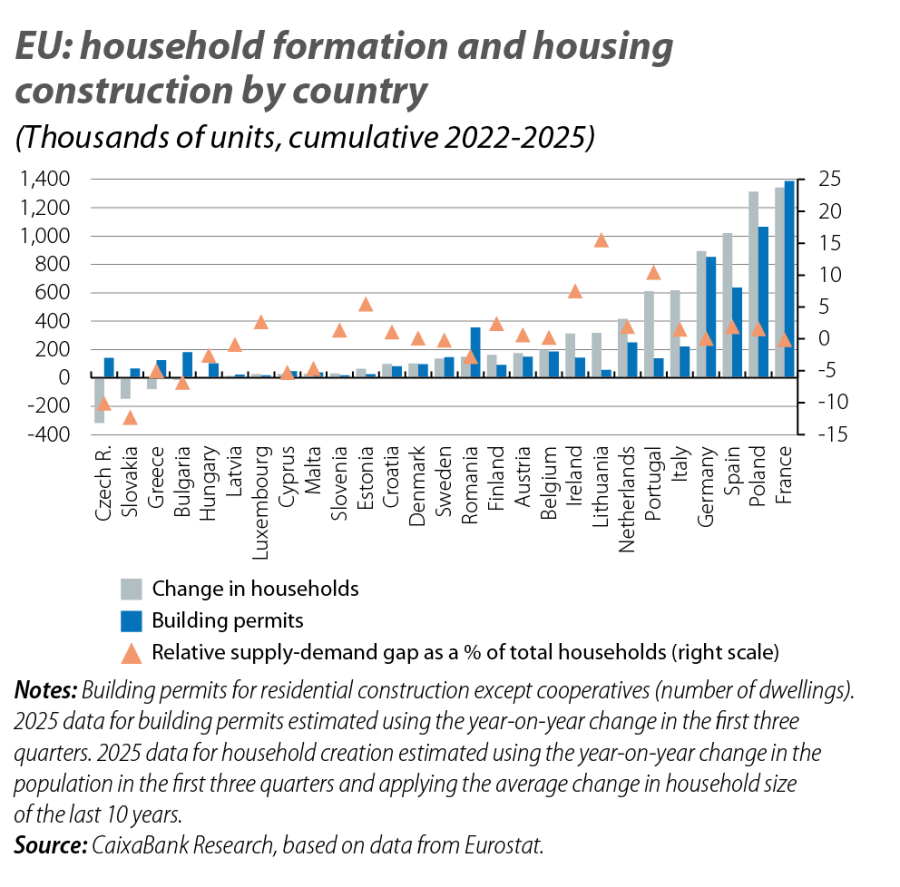

Some of the possible explanatory factors for the geographical dispersion include differences in the alignment between supply and demand, a different evolution of financial conditions and changes in the role of the second home segment.8 Here we focus on the first element, the one most linked to the medium-term fundamentals for the residential market. To this end, we compare the change in the number of households that has occurred in recent years (since 2022, to abstract from the demographic effect of COVID-19) with the provision of new homes based on construction permits (see fourth chart). In general, we observe a reasonable alignment between demand for primary housing and the supply of new homes, with the vast majority of countries having a supply surplus/deficit of less than 2% of the total number of households. However, it is worth highlighting some countries where the discrepancies are significant: Lithuania, Portugal, Ireland and Estonia show a recent imbalance exceeding 5% (double digits in the first two countries), while Italy, Finland, the Netherlands and Spain also stand out, with demand representing two or more years of new construction (up to seven years in the first case).9

- 7

However, the contained rise in rental costs for the stock of contracts contrasts with the strong increases observed in new contracts in recent years, of just over 30% per m2 between 2021 and 2025 according to data from Idealista.

- 8

See European Commission (2025). «Housing in the European Union: market developments, underlying drivers and policies».

- 9

For a more detailed calculation using alternative metrics for Spain, see «The price of not building: how the housing deficit explains much of the price pressures» in the Real Estate Sector Report for S2 2025.

The recent evolution of the European residential market reflects a cycle marked by successive shocks and an insufficient supply that is now emerging as the main source of tension. Although the price rally is widespread, the disparity between countries is clear, with differences in affordability and mismatches between supply and demand that limit the policy response. In this context, the Commission’s European Affordable Housing Plan is a step in the right direction, but only a coordinated strategy between different levels of government will allow housing to stop being Europeans’ top concern and become instead a pillar of social cohesion and economic stability.