China’s alchemy: how it transforms critical minerals into global power

In recent years, the discussion around critical commodities has emerged as a key element in the redefining of economic relations at a global level, in an environment marked by persistent geopolitical tensions. So-called critical minerals – such as rare earths, copper, or lithium – are key inputs for global industry and, specifically, for those sectors most closely linked to the green and digital transition. The demand for these commodities has grown sharply in recent years, as has the supply, driven by the largest global producers of many of these minerals, such as China, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

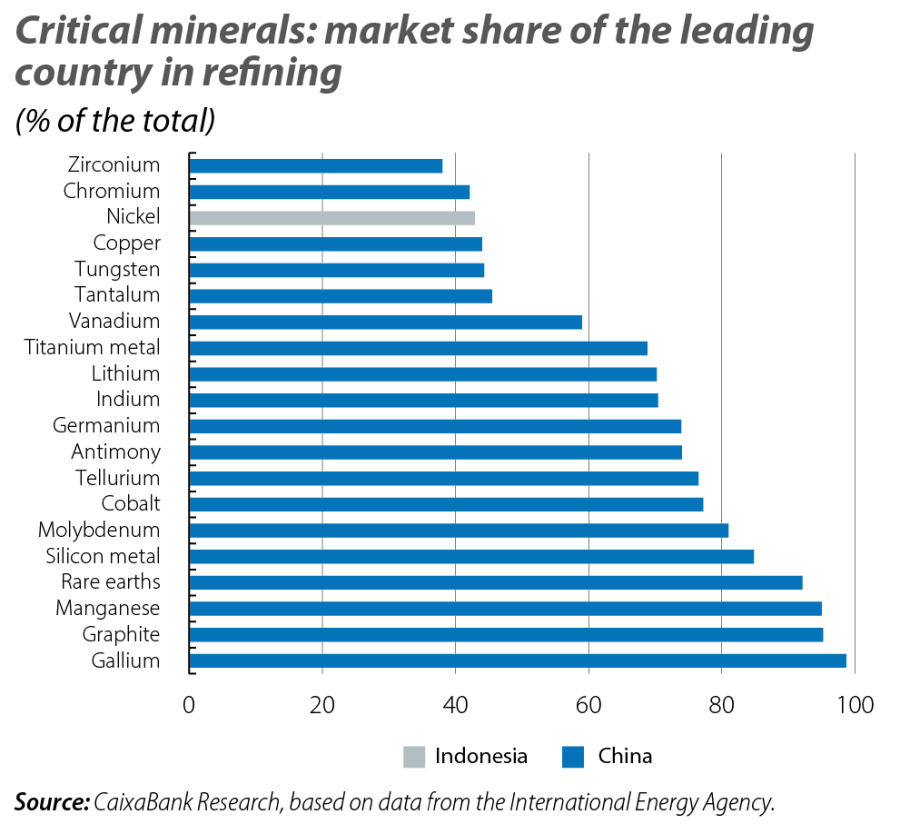

Also, the geographical concentration of the mining and processing of these commodities increased in the last decade.1 In this context, China continues to stand out as the leading power in the processing of these minerals, with market shares in excess of 70% in the refining of a wide range of products (see first chart).

- 1

According to data from the IEA, demand for lithium surged by around 30% in 2024, while demand for nickel, cobalt, graphite and rare earths grew by between 6% and 8%. On the other hand, a rebound in supply has allowed prices to fall slightly for several of these minerals, following an increase in 2021-2022. At the same time, the use of restrictive trade measures on these products has soared since 2023. See the IEA (2025) «Global Critical Minerals Outlook».

Strategic control of commodities that support global industry

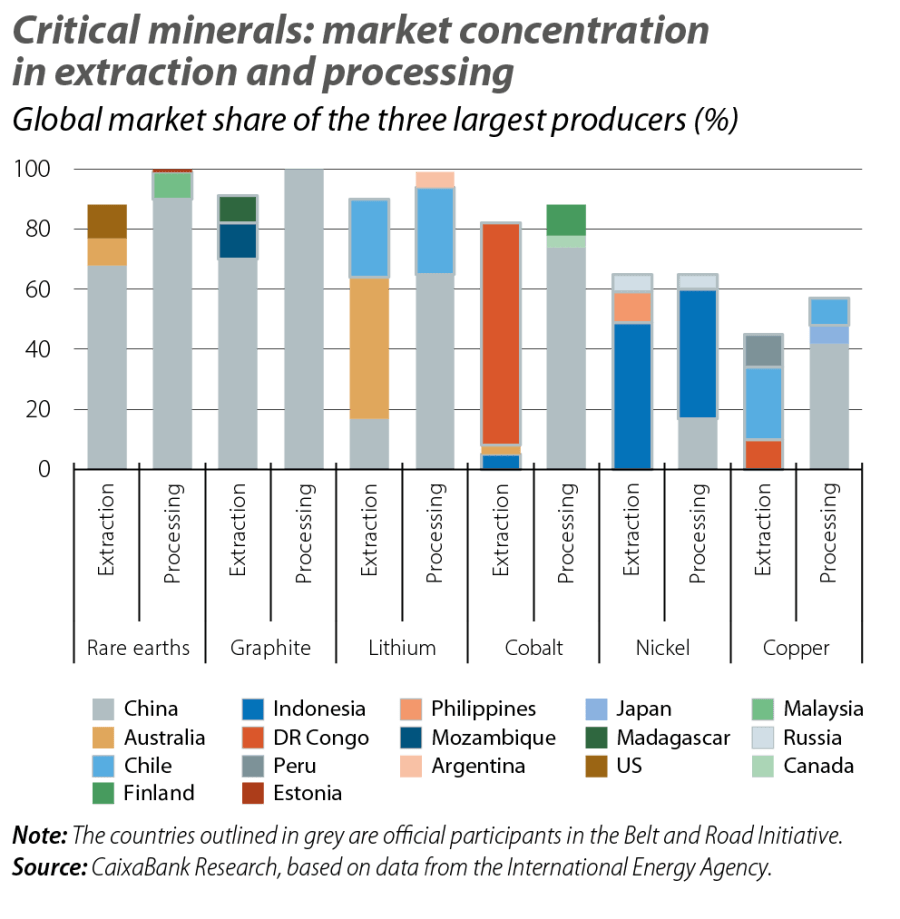

In the cases of rare earths and graphite, China’s leadership in the processing of these products is complemented by a high market share in their extraction. This gives the country a dominant position in the various stages of the value chain and allows it to effectively control their global supply (see second chart). On the other hand, in the cases of lithium, cobalt and copper, China’s dominance is concentrated in processing, while extraction is carried out in other locations. That said, in many cases, China has established a broad economic and diplomatic relationship with these countries, which is especially evident in the case of those participating in the Belt and Road Initiative. For instance, Chile is the largest global exporter of lithium carbonates (accounting for almost 80% of global exports), and two-thirds of its exports are destined for China. The Democratic Republic of the Congo accounts for around 60% of global cobalt exports, and almost all of these go to China. In this way, the dominant position that China has achieved in trade relations with several countries rich in these resources,2 coupled with its dominance in their processing, offers the Asian giant a near monopoly in key points of the value chain of various critical commodities. This dominance gives its industry a key comparative advantage and it can be transformed into a geo-economic lever.

- 2

Between 2000 and 2021, China invested around 57 billion dollars in critical mineral sectors in emerging and developing economies, more than 80% of which was in copper, cobalt and nickel projects (IEA, 2025). See also the Focuses «The Belt and Road Initiative: a double-edged sword? (part I) and (part II)», in the MR11/2025 and MR12/2025, respectively.

Critical routes: how rare earths move in global trade

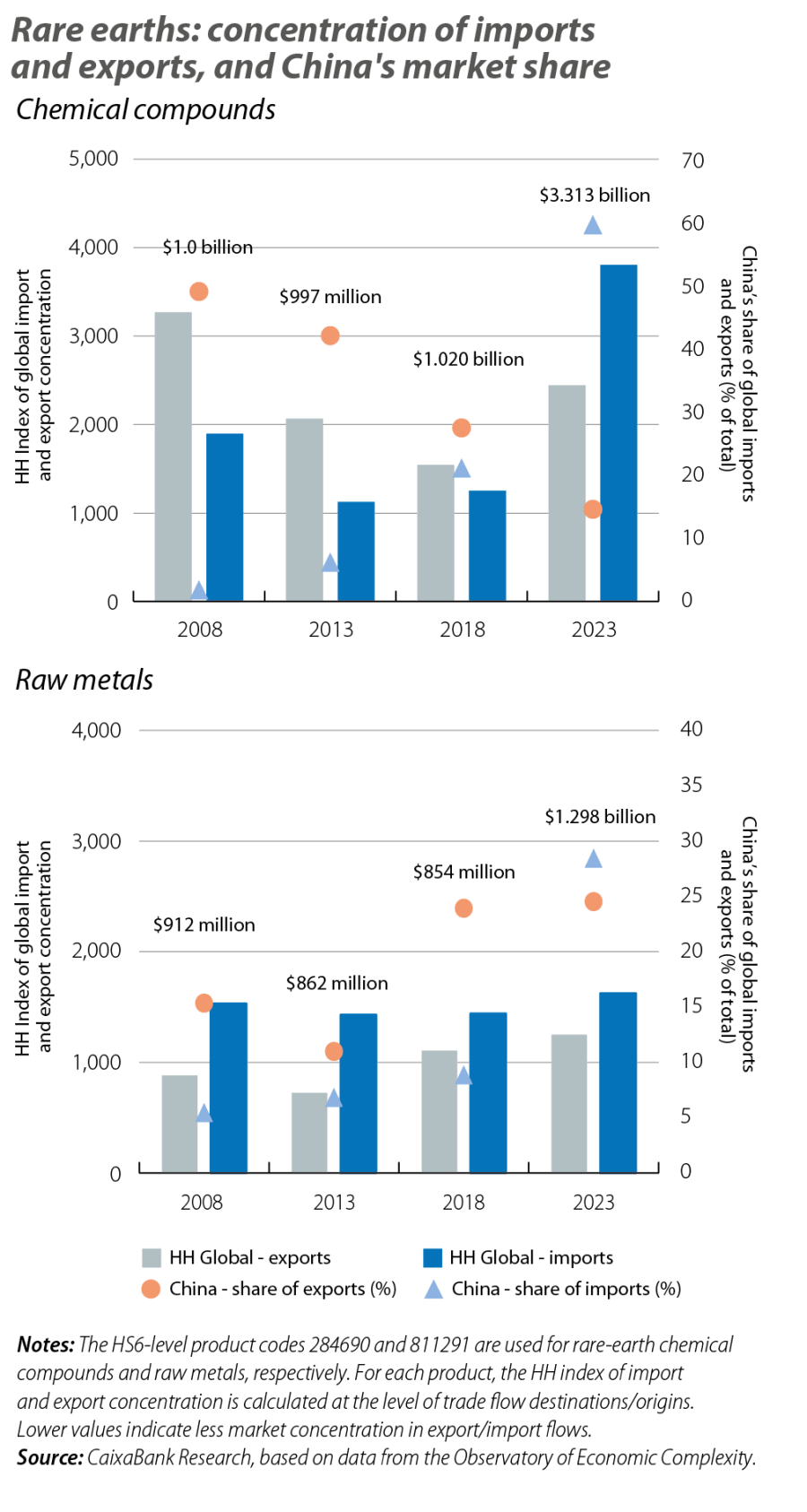

The case of rare earths is particularly illustrative of the strategy that China has pursued in recent years in order to achieve global dominance and use it to its advantage. On the one hand, China dominates over half of their extraction globally, while that share rises to nearly 90% in their processing. On the other hand, its global share of rare earth exports, in their various forms (chemical compounds, raw metals or articles manufactured from these metals), are comparatively low, ranging from around 15% in the case of compounds to 25%-40% in other forms – well below the market shares observed for extraction and processing.3

Specifically, in recent years there has been a steady reduction in China’s global share of exports of rare earth chemical compounds (precursors of raw metals), from around 50% to the current 15%, while its global share of imports has increased particularly sharply since 2018, reaching the current level of 60% (see third chart). Against this backdrop, there has been a rapid global concentration of imports, with China (the third-largest exporter) absorbing virtually all imports originating from Myanmar (the largest exporter) and 40% of those from Malaysia (the second-largest exporter). On the other hand, in the case of rare earths in raw metallic form or manufactured articles, China’s share of global exports has remained relatively stable, while its share of global imports has increased, especially in the less advanced stages of processing these products. Thus, China’s strategy has aimed for dominance over the reserves, extraction, and processing of rare earths, a vertical integration that grants the Asian giant an almost uncontested hegemony in the sector, and a unique advantage for industries that rely on these critical inputs.

- 3

After the mining phase (i.e. the process of physical extraction of the ore from rock deposits), the processing of these metals can be divided into five phases: concentration (crushing, grinding and separation, which increases the concentration of the desired element), chemical refining (conversion of the mineral into purer compounds), reduction to metal (the chemical process to remove oxygen and other elements, obtaining the raw metal), alloying (casting of the pure metal, and mixing it with other elements, conversion into ingots, powder or parts) and the manufacture of «final» products (use in magnets, batteries or other electronic components).

From extraction to innovation: the architecture of China’s dominance

In 2020, Xi Jinping described China’s dominance in certain strategic industries or technologies as its «assassin’s mace».4 Rare earths – one of the aces up the Asian giant’s sleeve – proved decisive in 2025 during the escalation of trade tensions with the US, and the announced restrictions have set off alarm bells in the rest of the world.

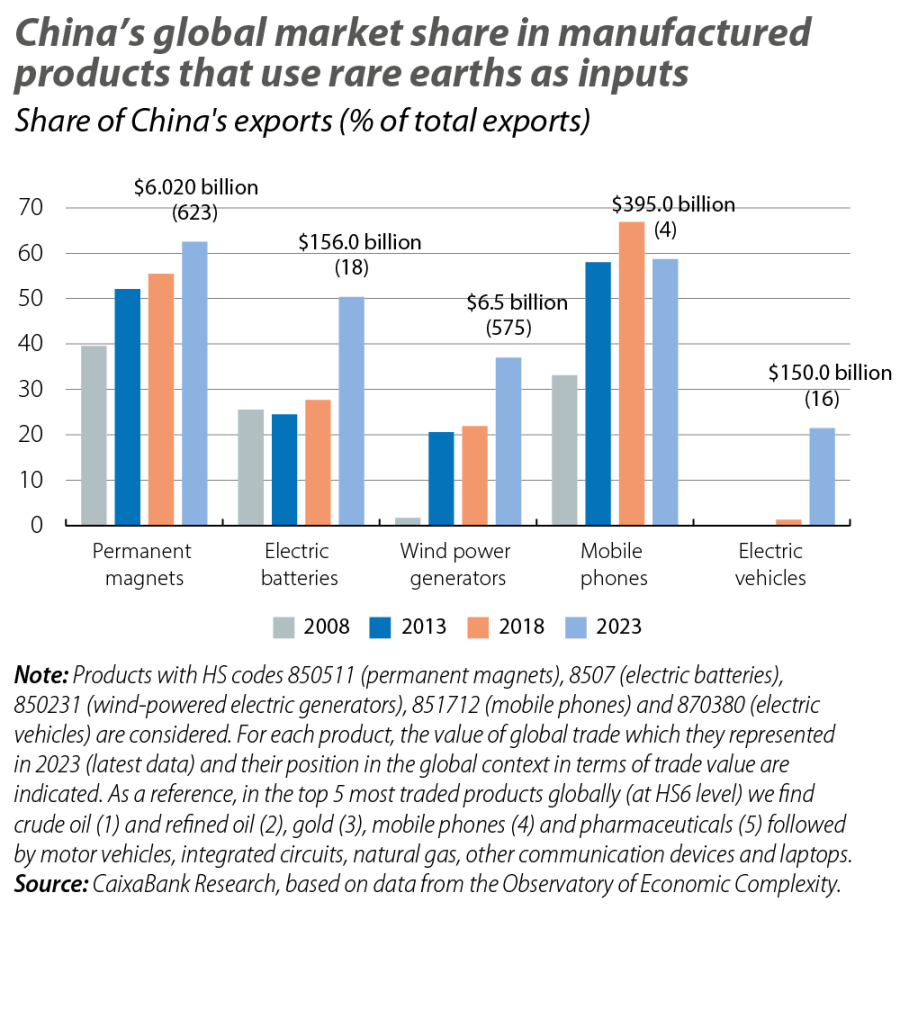

In addition to securing its hegemony over a wide range of critical commodities and enabling their use for more than exclusively trade purposes, China’s vertical dominance in these value chains has extended to several products that use them as a key input. In recent years, the country’s global market share in permanent magnets, electric batteries, wind power generators and electric cars has soared (see last chart).

- 4

See The Economist (2025). «Xi Jinping swings his “assassin’s mace” of economic warfare», 06/02/2025, or the translation of the original speech by Xi Jinping, in 2020, «Certain Major Issues for Our National Medium- to Long-Term Economic and Social Development Strategy» by CSET (Georgetown University). In Chinese, the term refers to a tool which, when used at a critical moment in a confrontation, proves decisive.

China’s success in several of the most important sectors for the global economy in the coming decades is due to a multitude of interrelated factors. One is the control of various critical commodities, which has paved the way for it to develop a comparative advantage in countless intermediate products that are key to several sectors, such as permanent magnets or electric batteries. In addition to its active industrial policy that has allowed it to gain scale and competitiveness, China has added other elements. On the one hand, massive investment in infrastructure has enabled it to have some of the most developed transport, telecommunications and energy networks in the world, and this has helped cultivate «economies of scope», facilitating the deployment of new technologies (such as those related to electric mobility) and providing competitive advantages to energy-intensive industries. On the other hand, a more flexible regulatory framework and a large workforce specialised in the industrial sector favour innovation and a build-up of «process knowledge», ensuring a comprehensive understanding of «factory processes» among its labour force. These elements enable the implementation of continuous improvements, the scalability of Chinese factories and the creation of new industries, such as electric vehicles, drones or robotaxis, ensuring dynamic competitive advantages in the industrial sector. Ultimately, China has transformed critical commodities into the cornerstone of tomorrow’s global industries.