The Belt and Road Initiative: a double-edged sword? (part III)

The BRI has become a key element for China’s global positioning. Faced with weakened domestic demand and chronic overcapacity, the initiative has facilitated the opening up of new markets, the diversification of export destinations, the dominance of value chains for critical commodities that are essential for its industrial development, and the reduction of dependence on geo-economic rivals, a factor that has gained particular importance in recent years.

Due to its speed and scale, China’s transformation in recent decades has also transformed the rest of the world. In particular, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has brought substantial investments to many of the participating countries. Coupled with an active industrial policy and a capital-intensive development model, this has favoured a rapid expansion of China’s trade flows, particularly in sectors with stronger links to its industry.1

- 1

See the Focuses «The Belt and Road Initiative: a double-edged sword?» (part I) and (part II), in the MR11/2025 and the MR12/2025, respectively.

Belt and Road: blessing or curse?

The Silk Roads were a network of routes that began to be used regularly beginning in the 2nd century BC, when the Han dynasty opened up trade with the West, and lasted until the 15th century, when the Ottoman Empire boycotted trade and closed the routes. During that time, from China to Europe, traders brought silks, jade and other precious stones, porcelain, tea and spices. To the East, manufactured goods such as glassware and textiles were transported. But these routes also provided a channel for cultural exchange and the exchange of ideas, as documented, for example, in The Book of the Marvels of the World, by the Venetian merchant Marco Polo.

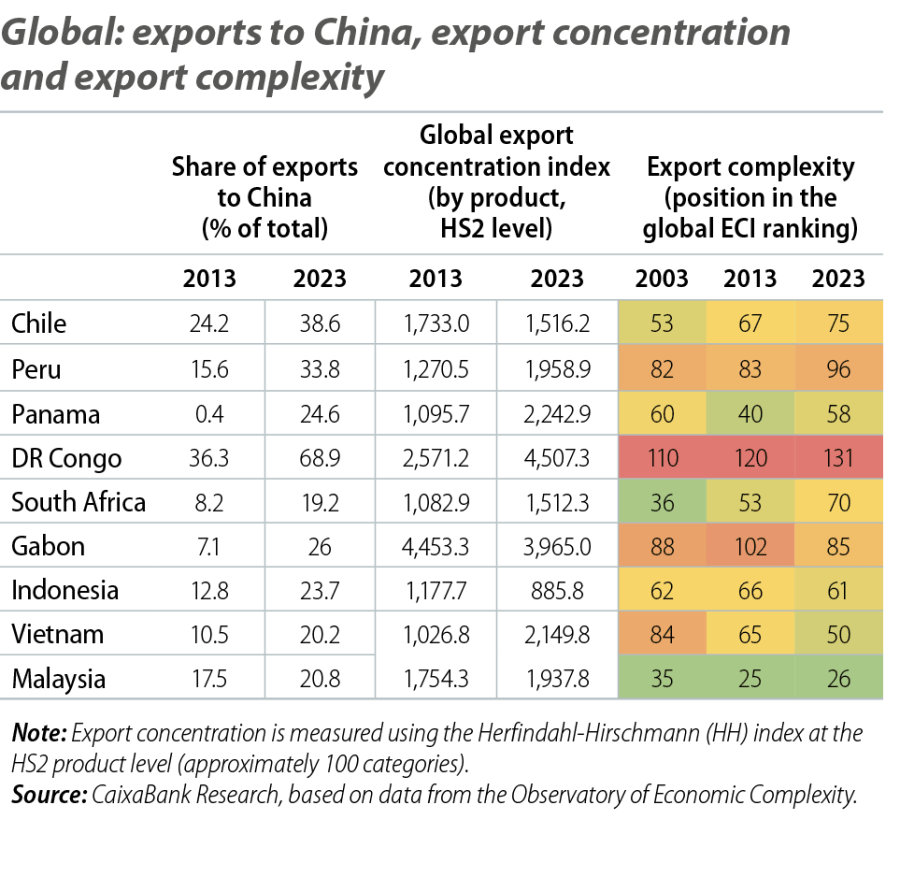

Today, at the various ends of the new Silk Road, the experiences of countries such as Chile, Peru, the DR Congo, Indonesia and Vietnam are illustrative. The first three countries are among the largest global producers of copper (and of cobalt, in the case of the DR Congo). In the last decade, the share of these countries’ exports that is destined for China has risen rapidly, reaching almost 40% in Chile and 35% in the case of Peru. In Peru, exports of copper ore have surged and now account for nearly 70% of its exports to China, while in Chile copper exports have grown steadily (although imports of refined copper have decreased) and the country has seen increases in exports of chemical products (such as lithium) and agrifood products. In the DR Congo, exports to China now account for 70% of the total, compared to 35% a decade ago – an increase explained by exports of cobalt and copper, mainly refined, but also in raw and mineral form.

The share of Indonesia’s exports destined for China has also increased significantly, from 13% to 24%, but the concentration in terms of products has decreased. Mining exports (fuels and metal ores, such as nickel and aluminium ore) have decreased, while metal exports have increased (including processed nickel, steel and ferroalloys), as the country banned nickel ore exports with the aim of developing its own refining industry. Exports of electrical and electronic machinery to other Asian countries and the US have also increased rapidly. Vietnam, meanwhile, has tripled the value of its exports in recent years while its share of exports destined for China has increased from 10% to 20%, and that of exports to the US from 17% to 28%. This growth has been driven by a significant expansion in electrical and electronic machinery.

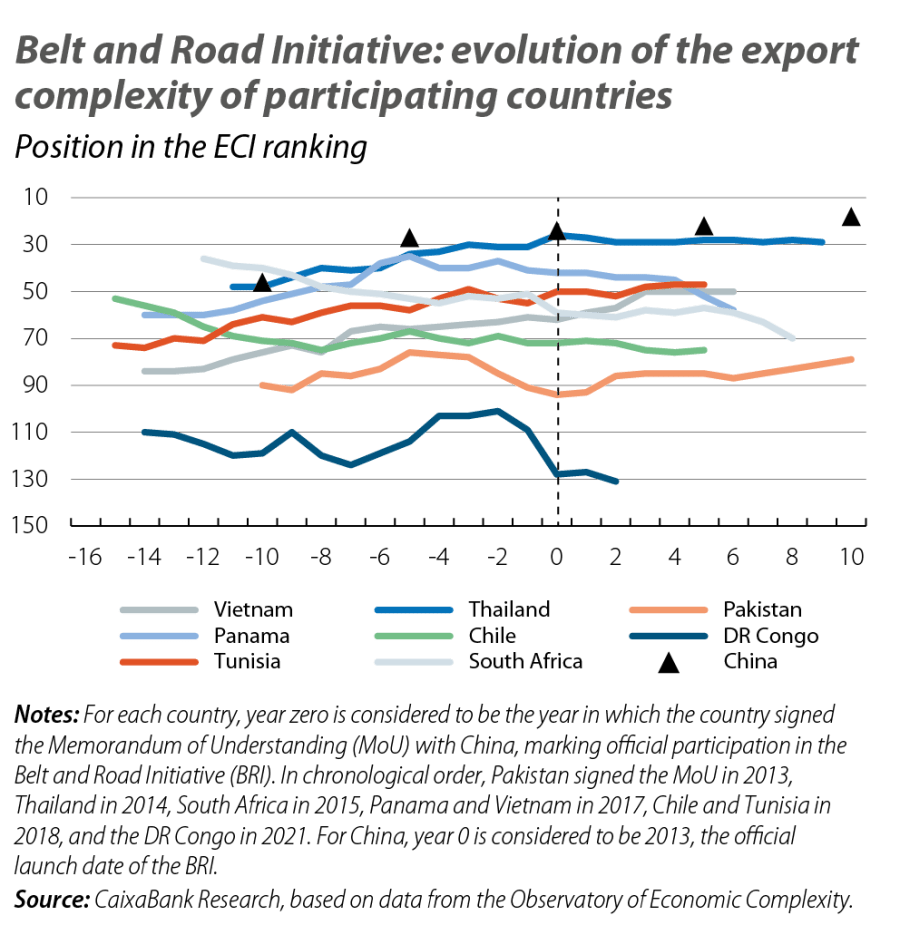

While Indonesia and Vietnam have climbed the global economic complexity ranking over the last decade, Chile, Peru and the DR Congo have fallen back (see first table).2 Hence, we analyse the relationship between participation in the BRI, used as an approximation for closer economic and diplomatic ties with China, and export complexity for a sample of 66 countries. The analysis focuses on Eurasia, the region that has received the greatest investment and is home to the largest number of countries participating in the initiative.3

- 2

The Economic Complexity Index (ECI) measures the intensity of an economy's knowledge, focusing on its technological capabilities. In particular, we use one of the three dimensions of the ECI – export complexity (along with technology and research) – due to its relevance and the availability of data.

- 3

Two definitions of participation in the BRI are used. The first is based on the signing of the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with China, which seals a country's official participation in the initiative. The second is based on the existence of operational infrastructure projects that are within the scope of the BRI, such as roads, railways or ports. A panel regression model is estimated, with data from 1995 to 2023, using fixed and random effects, control variables, and time fixed effects. The dependent variable (Yit) is interpreted as a measure of a country's trade and technological sophistication: \(Y_{it}=\beta_0+\beta_1BRI_{it}+\theta X_{it}'+\mu_i+\lambda_t+\varepsilon_{it}\). The list of operational projects is based on Reed and Trubetskoy (2019) «Assessing the Value of Market Access from Belt and Road Projects», Policy Research WP, World Bank

The econometric analysis reveals that participation in the BRI has a negative correlation with the economic complexity of the countries in the sample. The results are robust to different econometric specifications and to different definitions of official participation in the BRI. Overall, the results suggest that participation in the BRI does not contribute to the development of more sophisticated industries or to an improvement in export quality, understood as more diversified exports with higher technological content. On the contrary, participation in the BRI could limit participating countries’ ability to «climb» global value chains.4

- 4

See, for example, F. De Soyres, A. Mulabdic and M. Ruta (2020) «Common transport infrastructure: A quantitative model and estimates from the Belt and Road Initiative», Journal of Development Economics, 143, 102415 and S. Lall and M. Lebrand (2020) «Who wins, who loses? Understanding the spatially differentiated effects of the belt and road initiative», Journal of Development Economics, 146, 102496.

What can we learn from the new Silk Road?

The BRI has become a key element for China’s global positioning. Faced with weakened domestic demand and chronic overcapacity, the initiative has facilitated the opening up of new markets, the diversification of export destinations, the dominance of value chains for critical commodities that are essential for its industrial development, and the reduction of dependence on geo-economic rivals, a factor that has gained particular importance in recent years.

However, despite the substantial investment flows from China in sectors such as energy, transport, metals and mining, and construction, as well as a rapid increase in their exports, several countries along the new Silk Road may have seen the direction of their economic development become somewhat narrowed.5 The negative correlation between participation in the initiative and the economic complexity of the participating countries could be explained by various factors. By focusing on physical infrastructure, the BRI can facilitate Chinese companies’ access to local markets while weakening the competitiveness of the local business fabric. Emerging economies, specialising in basic manufacturing, could be displaced, while those rich in natural resources risk becoming trapped in low value-added extractive sectors. Furthermore, many BRI projects carried out by Chinese companies may offer limited direct benefits to local industries, a challenge that is further compounded by governance failures or institutional weaknesses, which also hinder the effective absorption of investments.

While the benefits of the BRI may materialise in the long term, given its recent launch, the observed short-term effects have been debatable. Added to this is the risk that BRI countries could develop economic dependencies on China, seeing their trade deficits, debt levels, and external vulnerability grow – a scenario that raises questions about the sustainability and reciprocity of the BRI. While effective for China’s strategic interests, does the initiative represent a genuine development opportunity for participating countries?

Simultaneously, China has intensified its commitment to global technological leadership, specifically in AI, robotics and semiconductors. These ambitions could promote technological and productive advances in BRI countries, while simultaneously causing losses of competitiveness and critical dependencies in sectors where China continues to gain global market share.6

Like the ancient Silk Roads, the BRI is not limited to investments or trade exchanges. Evaluating its success solely in these terms would ignore a broader geo-strategic purpose, such as ensuring stable economic relations and access to (or dominance of) key economic resources ahead of geopolitical rivals, or an assessment of potential institutional, social or cultural effects. Moreover, despite the large number of initiatives launched in response to the BRI (such as the G7’s «Partnership for Global Infrastructure» or the EU’s «Global Gateway» programme), their progress has been limited. As in the 15th century, the greatest risk to economic development would be the erosion of these routes. Then, after the fall of Constantinople, the Ottoman Empire imposed very high costs on trade between Europe and Asia. On the other hand, the blockade created incentives for the development of maritime trade and ultimately contributed indirectly to the cultural and scientific development of Western Europe. Ultimately, the Silk Roads stand as enduring witnesses to the ascent of a Chinese empire.

- 5

Among the participants in the BRI, countries such as South Africa (70), Chile (76), Kazakhstan (86), Mongolia (119) and the DR Congo (131) have fallen down the ranking of global economic complexity. In contrast, countries like Tunisia (47), Vietnam (50), Indonesia (60), Pakistan (81) and Bangladesh (92) have climbed the ranking.

- 6

In this area, the «Digital Silk Road» has sought to expand the country’s technological influence through investments in telecommunications, AI, smart cities and digital surveillance, offering solutions to bridge infrastructure gaps in emerging economies. On the other hand, it has raised concerns about the risk of facilitating state control over some technologies and compromising these countries’ digital sovereignty.