Debt limits: 2025 edition

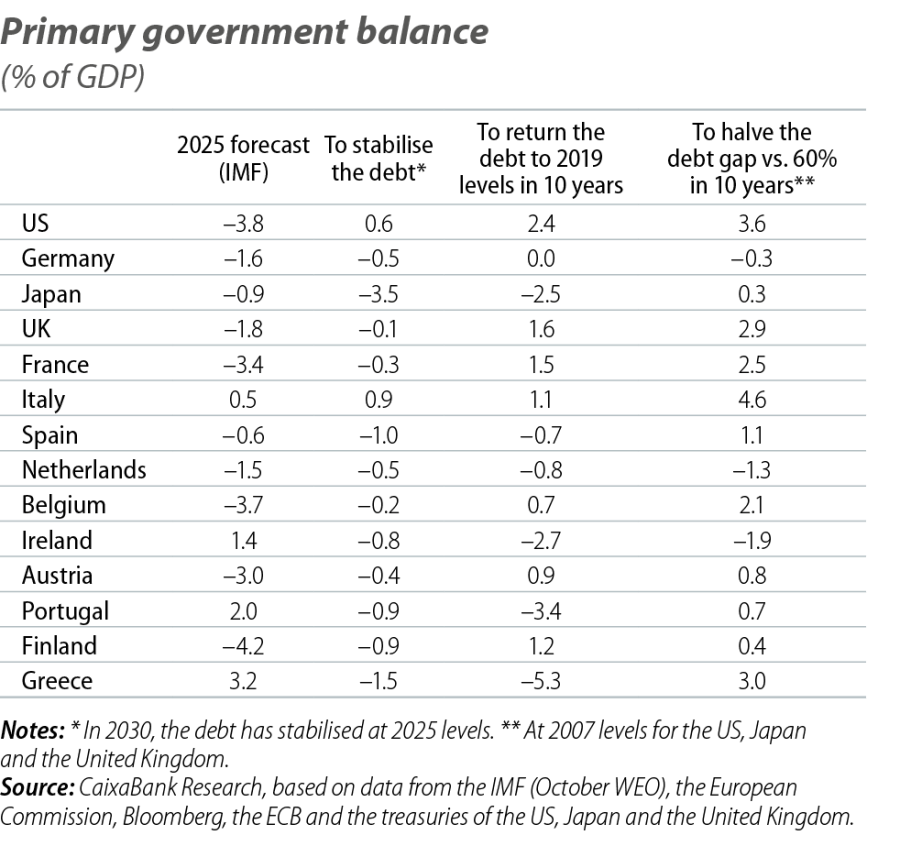

We analyse recent developments and the outlook for public debt in the major advanced economies. While the United States, France and Belgium will continue to see an increase in their ratios, Japan and the United Kingdom could stabilise them. In contrast, the euro area periphery shows favourable conditions for reducing its debt, although it will require significant fiscal effort.

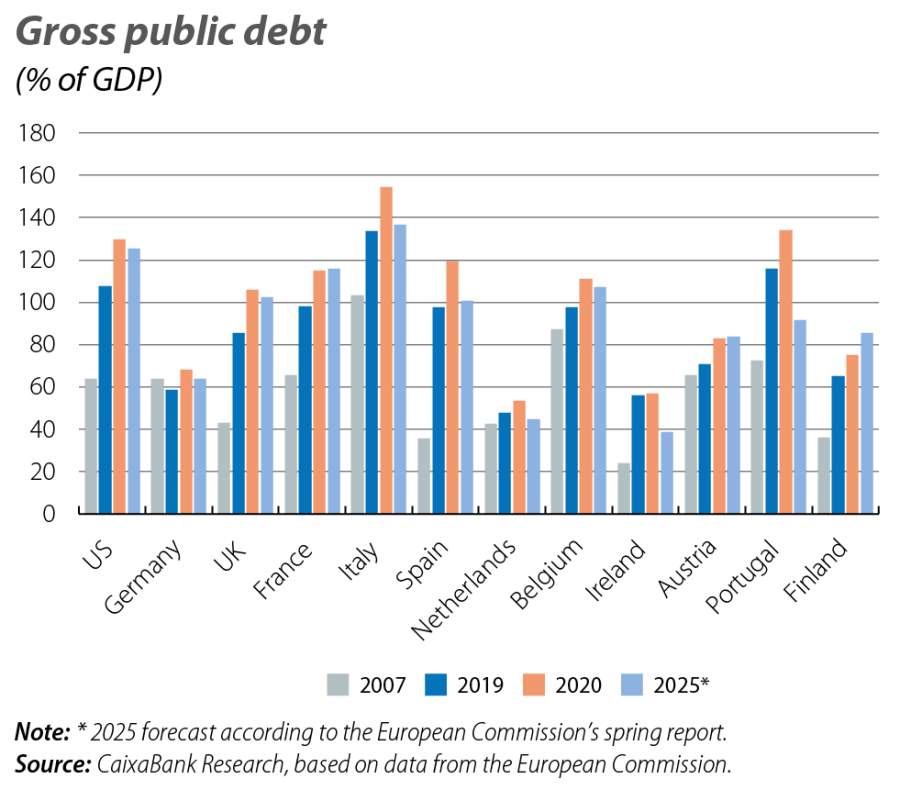

In recent decades, public debt has risen sharply and broadly, as we already discussed a year ago.1 Some of the countries that reached high peaks are now correcting course, but in other cases the levels remain high and there are no signs of them coming back down (see first chart). This has sparked occasional concern in financial markets, with investors becoming more sensitive to public finances.

- 1

See the Focus «Debt limits», in the MR01/2025.

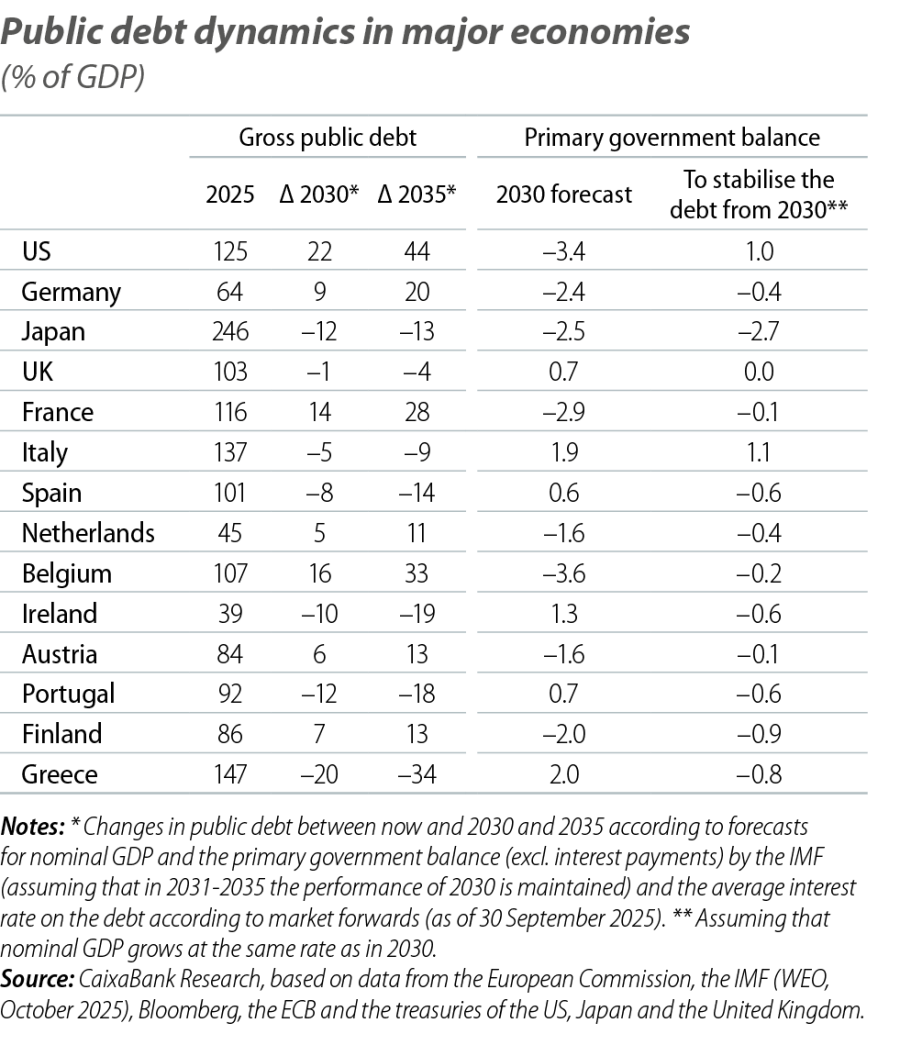

Some of the advanced economies that are showing no signs of correcting their high levels of debts include the United States, France, the United Kingdom, Belgium and Japan. The growth outlook for nominal GDP, the government balance and interest rates suggest that, in the coming years, public debt ratios will continue to deteriorate significantly in the US, France and Belgium (see first table).2 In all three cases, the expected increase in debt reflects the outlook of sustained high primary government deficits (i.e. excluding interest payments).3 In addition, in the US the gap between interest rates and weaker economic growth will also make it difficult to reduce the debt. In contrast, in Japan, the gap between rates and growth is expected to facilitate the reduction of the country’s debt, while in the United Kingdom the debt ratio is likely to stabilise at current levels if the outlook for rates, growth and fiscal policy is met.

- 2

Growth forecasts for nominal GDP (g) and primary government balance (b) per the IMF (World Economic Outlook autumn 2025 update). Interest rate forecasts (i) based on market forwards (measured according to the average maturity of each country), assuming that a percentage of the debt proportional to the average maturity is refinanced each year at the market rate. Taking these figures for g, b and i, we project the evolution of the public debt to GDP ratio (d) using the classic equation for debt dynamics:

\(d_{t+1}=d_t+\frac{i_{t+1}-g_{t+1}}{1+g_{t+1}}\times d-b_{t+1}\)

- 3

In the US, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB) estimates that the One Big Beautiful Bill Act passed by the Trump administration this summer will add more than 1.5 pps to the annual primary deficit in 2026 and 2027, and between 1.0 and 1.5 pps in 2028-2030, representing more than a third of the annual primary deficit forecast by the IMF. See CRFB (2025), «The 30-Year Cost of OBBBA». In France, parliamentary fragmentation makes it difficult to pass measures to reduce the country’s high primary deficit (3.7% in 2024).

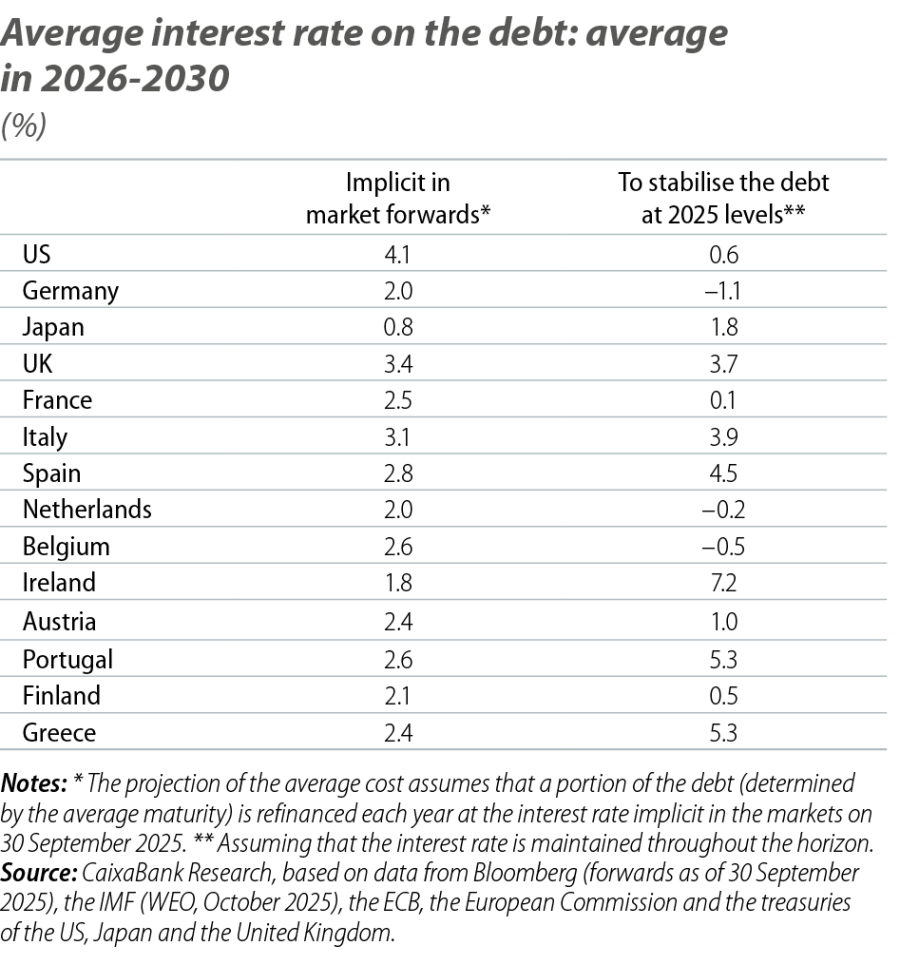

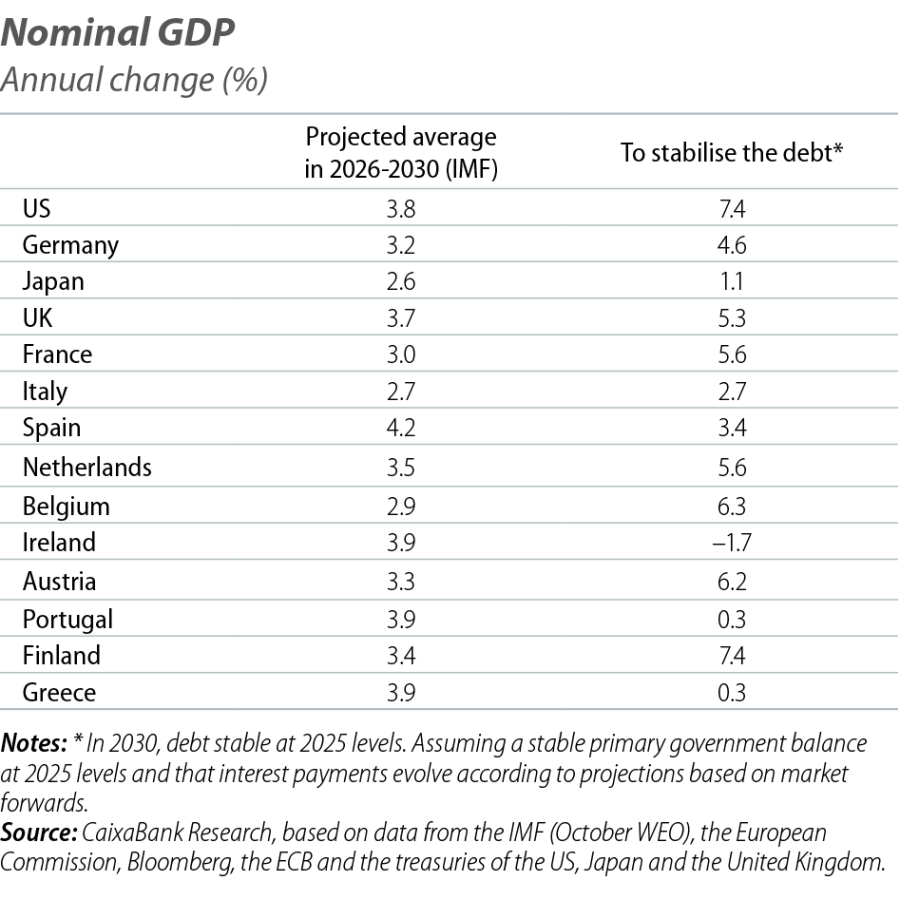

Reversing these trends will not be easy without substantial fiscal effort.4 Based on current GDP and interest rate forecasts, the US, France and Belgium will need to converge on an equilibrium primary fiscal balance at the very least if they are to begin reducing their debt ratios (see the last column of the first table). In the absence of changes to the path of fiscal policy, interest rates would need to fall sharply and/or nominal GDP growth would have to rebound strongly to stabilise and reduce debt (see the second and third tables). On the other hand, this does not mean that the sustainability of the debt is easily compromised by a rise in market interest rates. This is because rate increases in secondary markets are diluted by a relatively high average debt maturity (this mitigates the percentage of debt that is to be refinanced at a potentially higher cost). For example, given the current average debt maturities, we estimate that a sustained increase in secondary market interest rates of 100 bps would lead to an increase in the average cost of the debt, over an average horizon of 10 years, of around 25 bps across all the countries analysed overall (in the third year, the average impact would be around 15 bps, in the fifth year around 25 bps, and in the tenth year around 45 bps).

- 4

The projections of this article do not take into account the negative feedback that a significant fiscal consolidation would have on economic growth; such a situation would further complicate the state of the public accounts in the countries mentioned.

In contrast, the path followed by the euro area periphery and its growth and interest rate dynamics are, a priori, favourable for further reducing the debt ratios: as shown in the first table, in this scenario Italy, Spain and Portugal could achieve reductions of around 10 pps, 15 pps and 20 pps, respectively, in 10 years. Moreover, as seen in the second and third tables, the euro area periphery has a certain buffer that could allow it to withstand an increase in interest rates or a slowdown in GDP while still managing to reduce its debt ratios. However, these countries still face high debt levels, and making a deeper correction will require a significant fiscal effort, as the last table shows.5

- 5

The new EU fiscal rules, adopted in 2024, give some flexibility through medium-term adjustment plans. See «The new EU economic governance framework» in the MR01/2025.

Germany, for its part, is a special case. It currently has a low level of public debt, but projections for its GDP, rates and government balance point to a significant increase in its debt, led by investment and defence spending plans that have reoriented German fiscal policy in the last year.6

High debt is not necessarily a bad thing. Debt is a technology for storing wealth, managing crises, and investing in the future. The countries with the best credit capacity are those that can borrow the most. However, credit capacity can easily be eroded if the economy is unable to recover fiscal space when the economic environment is favourable. This is especially relevant after several years of strong nominal GDP growth and with the prospect of structural pressures on expenditure on the horizon (population ageing, defence and the energy transition).7

- 6

See the article «Europe’s medium-term fiscal dilemma», in the Dossier of this same Monthly Report, for a discussion on investment needs in Europe and the outlook for public debt.

- 7

According to the IMF, interest payments on public debt, population ageing (pensions and healthcare), the energy transition and defence spending in the major European economies will put additional pressure on annual public spending of 5.75% of GDP by 2050. IMF (2025), «Long-term spending pressures in Europe», Departmental Paper.