The impact of ageing on public finances: a major challenge for Spain and Europe

The ageing of the population will have a major impact on the public finances of advanced economies. The mechanism is well known: the ageing of the population and the consequent increase in dependency ratios can reduce tax revenues and increase public spending substantially. The main message of this article is that demographics will exert intense upward pressure on the public finances in Spain and Europe.

Ageing and public spending

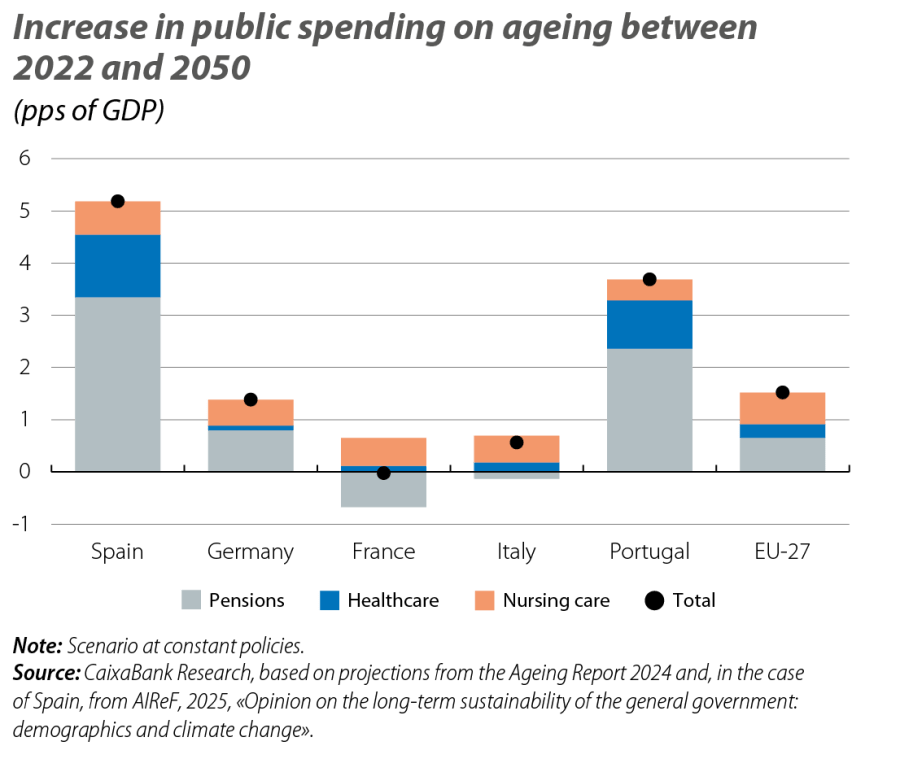

The portion of public expenditure directly affected by ageing which we take as a reference consists of pensions, healthcare and long-term nursing care. Public spending on pensions represents the bulk of the three (more than 60% in Spain) and AIReF1 estimates that, in the absence of changes in economic policies (what is known as a constant policy scenario), this category of expenditure in Spain would go from 12.7% of GDP in 2022 to 16.1% of GDP in 2050 (EU average estimated for 2050: 12.1% of GDP according to the European Commission’s 2024 Ageing Report, or simply AR24). This is an increase of 3.4 points, well above the EU average (+0.7 pps) and that of the other major European economies, including Portugal (+2.4 pps), as shown in the first chart.2 Two factors can help us to understand why pension spending will put greater pressure on the public finances in Spain than in the EU in the medium term. The first is the greater generosity of the public pension system: according to AR24 it is projected that, at constant policies, the replacement rate (i.e. the ratio between an individual’s starting pension and their final salary) will be 65% in Spain in 2050, compared to 38.5% in the EU.3 The second factor is the fact that, in Spain, the baby boom started almost a decade later than in central Europe (this second factor is expected to delay Spain’s peak pension spending as a percentage of GDP until 2045-2050).4

- 1

See the «Second Opinion on the Long-term Sustainability of the General Government» published by AIReF on 31 March 2025.

- 2

For the other economies, the anticipated increases are estimates from AR24. In the case of Spain, we take those published by AIReF, since it gives a more up-to-date scenario incorporating macro data from 2023 (only from 2022 in the case of AR24) and demographic projections that take into account recent demographic trends (AR24 uses Eurostat demographic projections from 2023). According to AR24, the increase in pension expenditure between 2022 and 2050 is, in fact, expected to be higher: +4.2 pps.

- 3

Currently 76.0% in Spain and 45.5% on average in the EU.

- 4

See the European Commission’s Annual Report of Taxation 2025.

The main determining factor that would explain the increase in public spending on pensions in Spain is demographics: it is estimated that, through the decline in the ratio of the working-age population to retirees, this could contribute an increase in pension spending of more than 8 pps of GDP between 2022 and 2050.5 Not surprisingly, in Spain, there are currently 2.6 people of working age for every person over 65 years, and by 2050, the National Statistics Institute (INE) projects that for every retiree there will be just 1.6 people of working age.6 The impact of demographics would be partially offset (see second chart) by the expected fall in the benefit rate (the ratio of the average pension to the average wage); due to the increase in the employment rate and a lower eligibility ratio7 (pensioners as a proportion of the retirement-age population). The reason for the importance of demographics is that, between 2022 and 2050, the number of retirees will steadily rise due to the retirement of the baby boomer generation,8 and that increase will not be offset by new entries into the labour market, even with dynamic migration flows.

- 5

We have rescaled the key figures from the Ageing Report 2024 to match the most recent AIReF reports which take into account the latest macroeconomic data.

- 6

See the article «Demography and destiny: the world that awaits us in 2050 with fewer births and longer lifespans» in this same Dossier. Estimates similar to those from AR24 and AIReF.

- 7

The eligibility ratio will help mitigate the increase in pension spending, especially during the first decade of the projection due to the gradual implementation of the increase in the statutory retirement age, reaching 67 in 2027.

- 8

See the Dossier «The golden years of the baby boomers: challenges and opportunities» in the MR06/2023.

Healthcare spending would also increase significantly, especially in Spain: in a constant policy scenario, it is estimated9 that this would increase by 1.2 points of GDP in Spain (+0.3 pps in the EU) to 8.0% of GDP (7.2% in the EU) between 2022 and 2050. In contrast, spending on nursing care would grow by 0.6 points of GDP, both in Spain and in the EU.

Thus, adding up pensions, healthcare and nursing care, the total public spending related to ageing in Spain would go from 20.3% of GDP in 2022 to 25.5% of GDP in 2050. This is an increase of 5.2 points, significantly higher than in the EU as a whole (+1.5 points). In terms of primary public expenditure, spending linked to ageing would represent 56% of the total in 2050 in Spain, compared to 48% today.

- 9

See the «Second Opinion on the Long-term Sustainability of the General Government» published by AIReF on 31 March 2025.

Demographics and public debt

The upward pressure of ageing on public spending is undoubted, but in order to get the full picture it is worth analysing the impact of ageing on public debt. AIReF has estimated that, in an illustrative scenario at constant policies,10 Spain’s public debt would increase by around 30 points of GDP between now and 2050, reaching 129% of GDP (debt in 2024: 101.8% of GDP), and it is documented that the ageing of the population and the increase in associated expenditure would be the trigger for this increase. In particular, AIReF estimates that the higher spending associated with ageing (pensions, healthcare and nursing care) alone would increase the debt by 57 points between now and 2050 (this would be partially offset by other factors, such as lower expenditure on education due to the reduction in the number of pupils, GDP growth, etc.). Of these 57 points, 31 would be driven by pension expenditure, 19 by healthcare and 7 by nursing care.11

- 10

It is assumed that no further measures are taken to rebalance the public accounts. In its macroeconomic forecast scenario, AIReF estimates population growth of 3.0 million between 2025 and 2050, an average annual growth in apparent labour productivity of 1.1% over the period 2025-2050 and an average annual growth in real GDP of 1.3% in the same period.

- 11

In other words, if the public finances were not conditioned by demographic pressures, debt would follow a downward path, reaching around 72% of GDP by 2050 (this figure is obtained by subtracting the upward contribution of demographics of 57 points of GDP from the estimated total debt of 129% of GDP).

A sensitivity analysis: the future is yet to be written and is not deterministic

Although the ageing of the population will put pressure on public finances, we must emphasise that the estimates analysed in this article are derived from illustrative inertial scenarios without any new economic policy measures beyond those already taken to date. Therefore, we should not succumb to despair.

It should be noted that a slight reduction in the growth of public spending (whether on items related to ageing or otherwise) would enable considerable savings that would go a long way to mitigating the increase in public debt and, therefore, the mortgage burden we would leave for future generations. Focusing on public spending related to ageing, we have already mentioned that with constant policies this would increase from 20.3% of GDP in 2022 to an estimated 25.5% of GDP in 2050. This is an average annual growth of 4.2% over the next 25 years. However, we estimate that reducing the average annual growth of such spending from 4.2% to 4.1% – which would bring it to 24.5% of GDP in 2050 instead of the 25.5% in the baseline scenario at constant policies – while keeping other factors unchanged12 would enable a much more gradual increase in public debt. Specifically, this would be 15 points of GDP lower in 2050 than in the baseline scenario (114% of GDP instead of 129%). Taking this scenario further, reducing the average annual growth of this expenditure from 4.2% to 3.9% – bringing it to 23.5% of GDP in 2050 instead of 25.5% in the baseline scenario – would lead to public debt being almost 30 points of GDP lower in 2050 compared to the baseline scenario (i.e. 101% of GDP instead of 129%).

In short, demographics will exert clear upward pressure on public spending in Europe and Spain in the medium term. However, the evolution of public finances in the medium term is highly sensitive to small changes in the assumptions used in the macroeconomic scenario, as well as to the estimates of increases in public spending, all of which is subject to the intrinsic uncertainty that surrounds the country’s macroeconomic evolution over the next 25 years. Moreover, the medium-term estimates are based on constant policies, but we cannot ignore the fact that the Spanish economy and those of Europe in general have a wide range of economic policy levers at their disposal to cushion and minimise the adverse impact of demographics on their public finances. Thus, there is considerable scope for action. It is precisely these levers that we discuss in the next article of this Dossier.13 The future is not written.

- 12

However, we take into account that a lower path of public debt also has an impact on the interest bill, which will be lower (leading to a snowball effect).

- 13

See «Levers to mitigate the impact of demographics on public finances: the case of pensions» in this same Dossier.