Levers to mitigate the impact of demographics on public finances: the case of pensions

Prolonging working life, boosting productivity and attracting more immigration are three of the levers proposed by economists to mitigate the impact of ageing on public finances in general and, in particular, on pension spending.

The upward pressure of demographics on public spending will be the dominant factor which, in the absence of measures, would lead to a deterioration of the public finances of developed economies in the medium term.1 Broadly speaking, in a scenario with constant policies, AIReF projects that public spending on ageing in Spain will increase between 2022 and 2050 by more than 5 points of GDP, of which 3.4 would correspond to pension spending, compared to a 1.1-point increase in revenues from social security contributions.2It would therefore be necessary to increase revenues by 2.3 points of GDP via transfers from the government to the Social Security system in order to finance the higher pension expenditure, unless measures are taken to reduce expenditure as a percentage of GDP.3

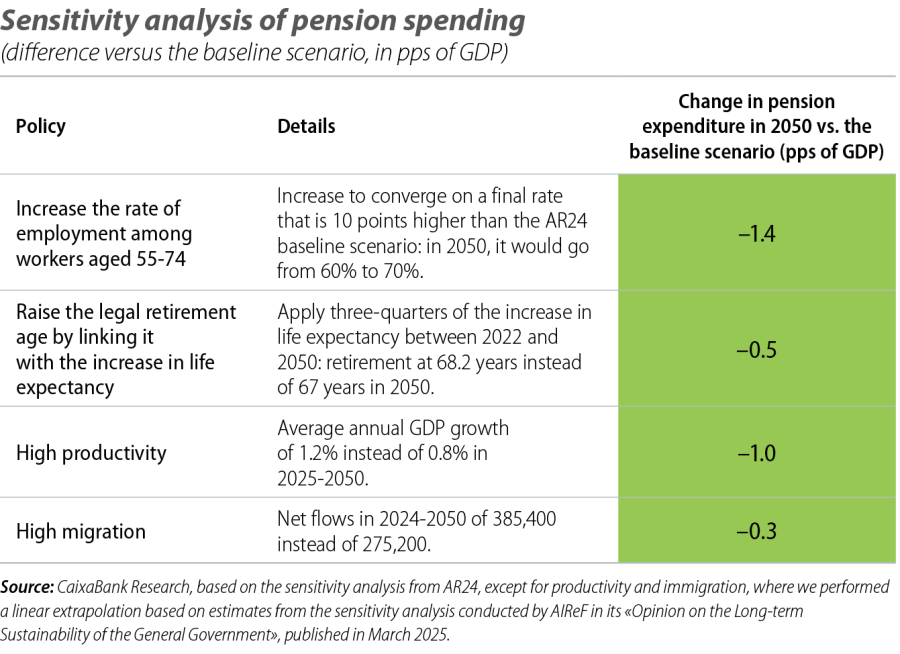

In this article, we focus on three major levers proposed by economists to mitigate the impact of population ageing on public finances and, in particular, on pension spending: prolonging working life, boosting productivity and attracting more immigration.4 Institutions such as AIReF and the European Commission have conducted sensitivity analyses on how changes in these levers could affect pension spending as a percentage of GDP in Spain. These are illustrative results that should be taken with caution given the high uncertainty surrounding the country’s future macroeconomic path over the next 25 years. In addition to these levers, we should also consider policies aimed at bolstering private pension schemes as an essential complement to public pensions, as well as measures to incentivise child birth.5

Starting with prolonging working life, increasing the employment rate among people aged 55 to 74 would considerably ease the pressure of ageing on pension spending. The Ageing Report 2024 (AR24) estimates that successfully raising this rate in Spain to 70% by 2050, rather than the 60% predicted in its baseline scenario with constant policies, would allow pension spending to be reduced by 1.4 points of GDP in 2050 compared to the baseline scenario – almost half the projected increase in expenditure (3.4 points). Achieving an employment rate of 70% by 2050 for people aged 55 to 74 seems ambitious; in the major European economies, also with constant policies, the projections for the employment rate in this age group in 2050 fall below that figure.6 In Spain, the current rate is 54%, so reaching the level of 60% anticipated7 in the baseline scenario would already represent a substantial improvement of 6 points, which incorporates the impact of the new design for the system of incentives to delay retirement under the 2023 pension reform.8 Policies that go further in this regard, such as allowing work and the receipt of a pension to be combined, would help to further boost the employment rate among these groups.

One avenue that other countries have followed to extend working life is to delay the legal retirement age. In AR24, they analyse the impact of delaying retirement by linking it to the increase in life expectancy; specifically, applying three-quarters of the increase in life expectancy9 between 2022 and 2050. This would mean that the legal retirement age in Spain would increase from 66.2 years in 2022 to 68.2 years in 2050, as life expectancy is expected to increase by almost three years in that period. The impact of this delay in the retirement age alone would represent a reduction in pension spending of 0.5 GDP points in 2050 compared to the baseline scenario in which the retirement age rises to 67 years in 2027 and remains constant at that age from then until 2050. Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden and Estonia have already linked retirement age to life expectancy. These countries also tend to be in more favourable positions in terms of the sustainability of their pension systems.10

Improving productivity is the second major lever analysed in this article to counteract demographic pressure on public finances. Productivity is the main source of economic growth in the medium term, so accelerating it would reduce pension spending as a percentage of GDP, although the positive impact via greater economic dynamism would be partially offset by higher pensions driven by higher wages. It is estimated that an average growth rate of total factor productivity (TFP) of 1.2% over the next 25 years, instead of the 0.8% envisaged in AIReF’s baseline scenario, could decrease pension spending in 2050 by 1 GDP point and public debt by around 20 points compared to the baseline scenario.11 If sound economic policies are implemented – in education, attracting talent, and a good institutional environment, etc. – and if the deployment of artificial intelligence has a successful impact, it is not unreasonable to aspire to achieve that pace in the medium term, even though it is an ambitious goal. To contextualise this scenario, the average annual growth rate of TFP in Spain was 0.9% between 2015 and 2019.

Finally, immigration can be a lever that also contributes in the desired direction, since it is the demographic phenomenon that has the quickest and most direct impact on the working-age population, a key element for GDP growth. It is estimated that net migration flows of 385,400 people per year on average in the period 2024-2050, as predicted by the National Statistics Institute (INE), rather than the 275,200 used in AIReF’s baseline scenario, would reduce pension spending in 2050 by 0.3 points of GDP compared to this baseline scenario, thanks to the greater growth of the economy.12 In addition, public debt in 2050 would be reduced by around 10 points of GDP compared to the baseline scenario thanks also to public revenues contributed by this group linked to their labour incomes. To contextualise the estimation of flows, in the period 2000-2023 they averaged 356,000 per year13 and reached 630,000 in 2000-2008. However, there is significant uncertainty over the impact of this lever; according to the AR24 analysis, the reduction in pension spending as a percentage of GDP thanks to immigration would be greater, albeit based on different assumptions.14

- 1

See the article «The impact of ageing on public finances: a major challenge for Spain and Europe» in this same Dossier.

- 2

See the «Second Opinion on the Long-term Sustainability of the General Government» published by AIReF on 31 March 2025.

- 3

See the Focus «AIReF’s evaluation of the pension reform: first match ball saved, but with big challenges on the horizon» in the MR05/2025.

- 4

Levers to mitigate the macroeconomic impact of ageing are discussed in detail in the article «The effects of ageing on growth and policy tools to mitigate them» in this same Dossier.

- 5

We discussed the first one in detail in the article «How to manage our cognitive biases to boost private pension savings» in the Dossier of MR06/2023, and the effects of the latter would possibly become evident beyond 2050.

- 6

Projections of the employment rate for this age group in 2050: 63.4% in France, 64.8% in Germany, 59.9% in Portugal and 55.9% in Italy.

- 7

It would go from 57.6% in 2022 to 72.5% in 2050 for the 55-64 age group and from 6.0% in 2022 to 18.2% in 2050 for the 65-74 age group.

- 8

The reform regarding delayed retirement includes a standardisation and increase of the additional percentages applicable for each year of delay in calculating the initial pension, as well as the possibility to replace the increase in the pension with a lump-sum payment calculated on the basis of the number of years of social security contributions, the years of delay and the initial pension. AIReF anticipates that these measures will contribute to an increase in the effective retirement age from 64.7 years in 2021 to 65.2 years today and to a forecast of 66.2 years in 2050.

- 9

Life expectancy at 65 years of age.

- 10

Specifically, their public pension expenditure as a percentage of their tax revenues is lower than the European average, as analysed in the European Commission’s Annual Report of Taxation 2025.

- 11

Extrapolation based on the sensitivity analysis performed by AIReF regarding the impact of increasing TFP growth by 10% in the «Second Opinion on the

long-term sustainability of the general government: demographics and climate change». - 12

We performed a linear extrapolation based on the sensitivity analysis conducted by AIReF, according to which a 15% increase in net migration flows in the period 2024-2050, starting from 275,200 a year in the baseline scenario, would reduce pension spending by 0.1 pp of GDP compared to the baseline scenario.

- 13

Excluding 2020 and 2021, years of reduced mobility due to the pandemic.

- 14

In AR24 the baseline scenario is net flows of 227,000 per year on average in the period 2024-2050. They estimate that a 33% increase in these flows to more than 300,000 per year would reduce pension spending by 1.4 points of GDP compared to the baseline scenario.

In order to measure the impact of immigration on public finances more fully, an analysis is needed to compare the contributions made by immigrants to public revenues against the benefits they will receive throughout their life cycle (e.g. the impact will be more positive in the case of young immigrants with high levels of training and strong professional skills). AIReF’s forecasts reveal how the ageing process would be mitigated in the 2030s and 2040s – the peak phase with the retirement of most baby boomers – by the incorporation of immigrants of ages at which the contribution to the public sector is positive. Subsequently, these cohorts of immigrants would reach their negative contribution stage once the process of the ageing of the native population has stabilised and, therefore, the pressure of increasing expenses associated with ageing has eased.

In short, with constant policies, it is projected that public spending on pensions will increase in Spain by more than 3 points of GDP over the next 25 years, or 2.3 points of GDP if the expected increase in income is factored in. Dynamic productivity growth, higher retention of older workers in the labour market and the attraction of highly educated immigrants could offset those 2.3 points completely in the best of worlds, or at least mitigate them considerably. At least, that is the case according to sensitivity analyses, which are subject to the inherent difficulty of making macroeconomic and demographic assumptions over such a long time horizon. Therefore, the room for manoeuvre exists and now is the time to get down to work.