Has employment growth in Spain been of higher quality since the pandemic?

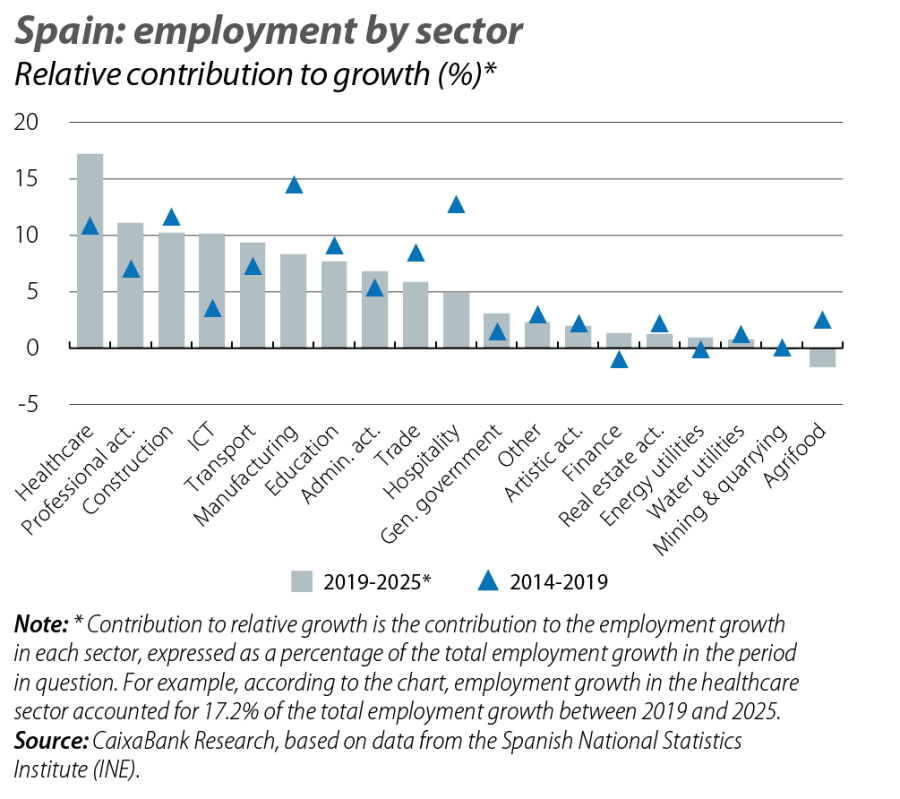

Employment has enjoyed a strong recovery in Spain since the pandemic. Between 2019 and the first three quarters of 2025, the number of people in employment grew by 11.9%. In addition, the sectoral distribution of this boom differs from the expansionary cycle of 2014-2019. Sectors such as healthcare, professional and scientific activities, and technology have gained prominence, while manufacturing and traditionally job-intensive areas such as trade, hospitality and agriculture have played a smaller role. These dynamics raise a key question: is the employment created in this phase of higher quality than in previous expansions? To answer this question, we have analysed three key aspects: workers’ qualifications, the trend in temporary employment – as an indicator of stability – and real wages.

Better qualified workers

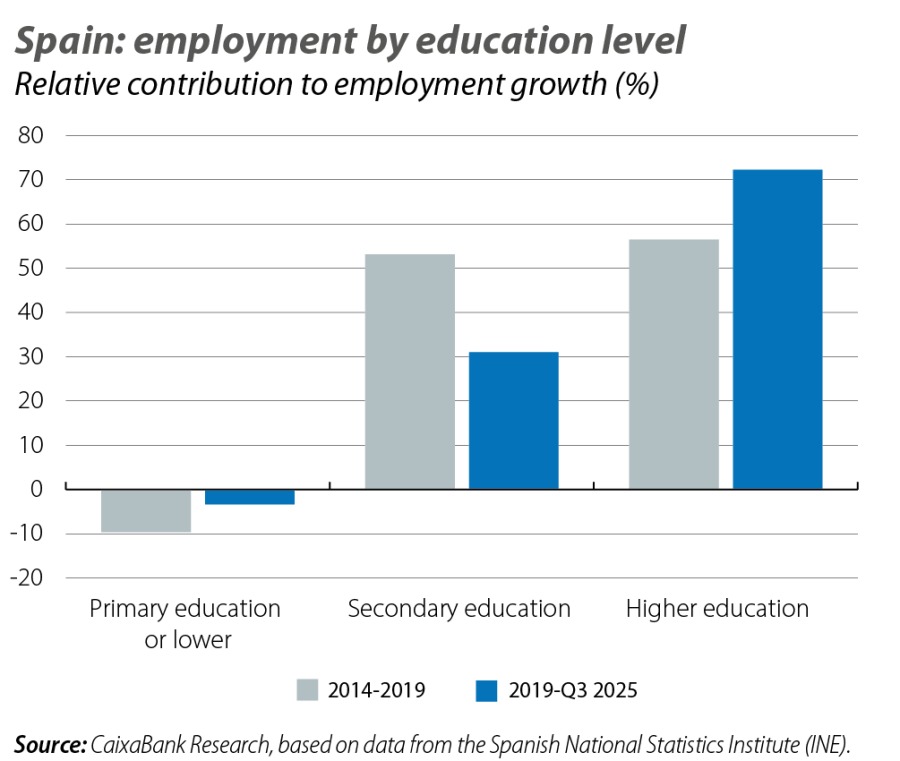

A more skilled workforce usually means more human capital and higher productivity. In this regard, the data show a clear improvement in the education level of employees in Spain.

Between 2019 and 2025 (up until the latest available data), over 70% of the employment growth corresponds to people with university or equivalent studies – a much higher proportion than in the period 2014-2019. In contrast, the employment of workers with secondary education grew less and that of workers with low education levels continued to decline, as was the case in 2014-2019.

Sharp fall in temporary employment

Job stability is another pillar of the quality of work. Spain has historically had a high rate of temporary contracts, but since the 2021 reform this proportion has plummeted, going from 26.6% on average in the period 2017-2019 to 15.4% on average in the first three quarters of 2025, converging on the figure for the euro area as a whole (13.5%).1 This decline has improved job stability.

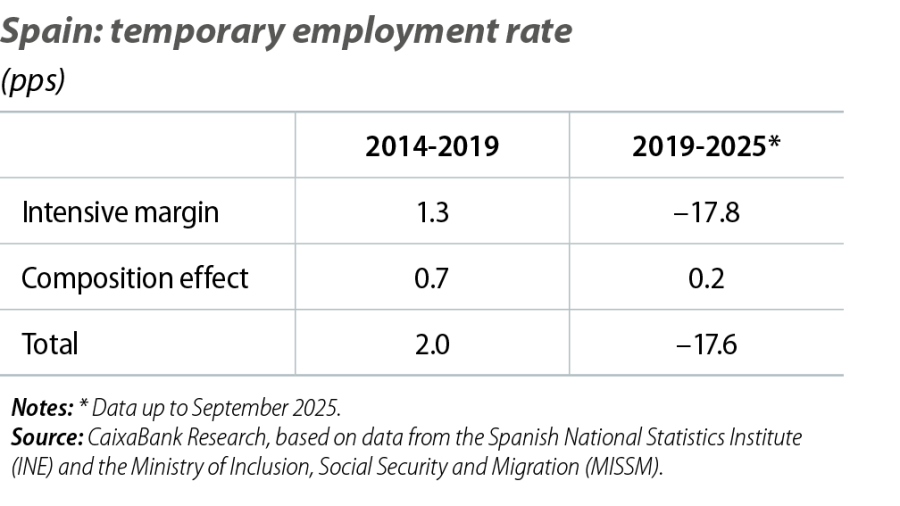

To better understand this change, we can break it down into two effects:

- Composition effect: this is the part of the change in the temporary employment rate that occurs due to changes in the relative weight of the various sectors. For example, if sectors that traditionally have a low temporary employment rate grow and those with a high temporary employment rate shrink as a proportion of the total economy, the aggregate rate will decrease due to this effect.

- Intensive margin: this is the part of the change that occurs due to changes in the temporary employment rate within each sector. In our context, this margin reflects whether companies in each sector are using more or fewer permanent contracts compared to temporary contracts than previously.

Applying this breakdown to recent developments, we find that the sharp reduction in temporary employment between 2019 and 2025 is entirely due to the intensive margin (see table). In other words, all sectors have substantially reduced their temporary employment rate, driving the overall decline. This result was to be expected, as it reflects the cross-sectoral nature of the impact of the labour reform on temporary employment. The sectoral composition of employment, meanwhile, has acted slightly against this reduction, but its impact was negligible. This contrasts with the previous expansive cycle (2014-2019), when the temporary rate increased by 2 pps, driven by both an increase in the intensive margin and an adverse composition effect of a greater magnitude than we have seen in the last five years (+0.7 pps vs. +0.2 pps).

- 1

Data from Eurostat. According to Social Security affiliation data, the temporary employment rate in Spain was around 12% in 2025.

Evolution of real wages

Finally, we analyse how real wages have evolved during this current phase. To do this, we use the Quarterly Labour Cost Survey, which measures the average wage cost per worker and per sector, and we adjust the data based on the CPI in order to obtain figures in real terms.2

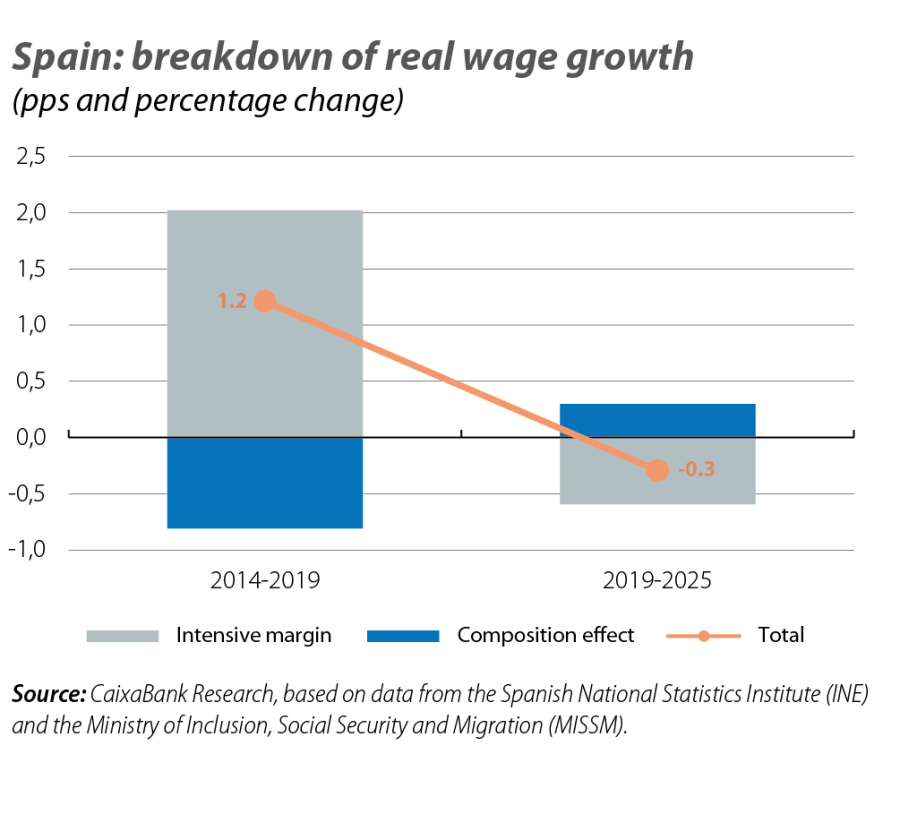

Between the average for 2019 and the first three quarters of 2025, the average real wage fell slightly, by 0.3%. However, this overall result hides two opposing forces:

- Composition effect: this has been positive. Employment has been more concentrated in high-wage sectors, contributing approximately +0.3 pps to the average wage growth. This change represents a shift from the cycle of 2014-2019, when employment was created mainly in low-wage sectors, deducting −0.8 pps from wage growth.

- Intensive margin: this has been negative. Within most sectors, wages have not grown at the rate of inflation, deducting 0.6 pps from growth. In other words, although the sectoral composition has favoured an increase in the average wage at the aggregate level, the loss of purchasing power within each sector more than offsets that effect.

- 2

The sectoral information is taken from the National Classification of Economic Activities (CNAE) at the two-digit level of detail, which comprises almost 80 sectors.

Conclusions

The indications analysed suggest that employment growth in Spain in the last five years has, overall, been of higher quality than that of the previous expansion. Several factors support this claim:

- The labour force has become better qualified, with employment rising predominantly among workers with a higher level of education.

- Labour stability has improved substantially: the temporary employment rate has fallen to record lows, thanks to a widespread decline across all sectors following the 2021 reform. This means more stable and predictable jobs than in the recent past.

- Employment has grown more in high-wage sectors, reversing the regressive pattern of the 2014-2019 phase.