Hours worked and productivity: is Spain an outlier in the EU?

The debate over working hours has intensified significantly in Spain, on the one hand, due to proposals for its reduction, and on the other, due to the rise in hours lost due to temporary sick leave. Beyond the impact on business costs and the labour market, the implications for labour productivity are of particular interest, with widely divergent readings since the pandemic in the case of Spain depending on whether we measure it per hour worked or per employee. This article places these debates within the broader the European context, drawing similarities and differences with other countries in our vicinity.

A secular downward trend, but with nuances

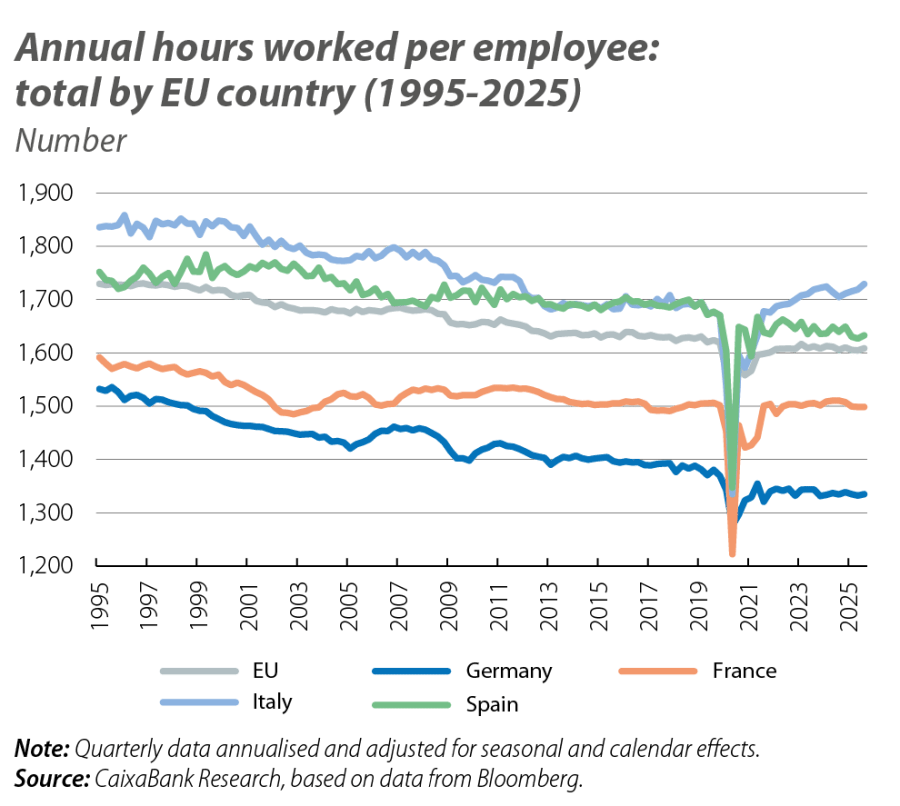

The number of hours worked per employee in the EU has decreased by 7% over the last three decades, from around 1,730 hours per year in 1995 to just over 1,600 hours today (see first chart). Behind this common trend (also noted in other developed economies), there are some notable differences.

Firstly, while the change in France, Italy and Spain is very similar to that observed in aggregate, the decline has been far greater in Germany (almost 200 hours less, 13% versus the initial level), deepening its position among the bloc’s four major economies as the one with the fewest hours worked. Secondly, most of the decline in the number of hours worked occurred between 1995 and 2005, particularly in France following the reform at the beginning of the century, which reduced the working week from 40 to 35 hours. Spain and Italy, meanwhile, exhibit exceptional and contrasting pattern, with a steady acceleration in the decline of hours worked in the former and a reversal of the previous trend in recent years in the latter.1

Thirdly, we can identify some common factors behind the secular reduction in working hours, such as the increase in part-time employment (whether voluntary or involuntary), a greater proportion of employment among the female population, in the service sector and among older workers – groups that on average have shorter working hours – and a greater preference for leisure time (reflected, for example, in a continuous decline in overtime hours).2 There are, however, other elements that have emerged in the post-pandemic period,3 such as the greater (lesser) dynamism of certain economic activities with a number of hours worked below (above) the average, such as public administration (industry),4 the labour shortage in some sectors – which, following the shock of the war in Ukraine, may have favoured the retention of workers with less intensive use – and the increase in temporary sick leave.5

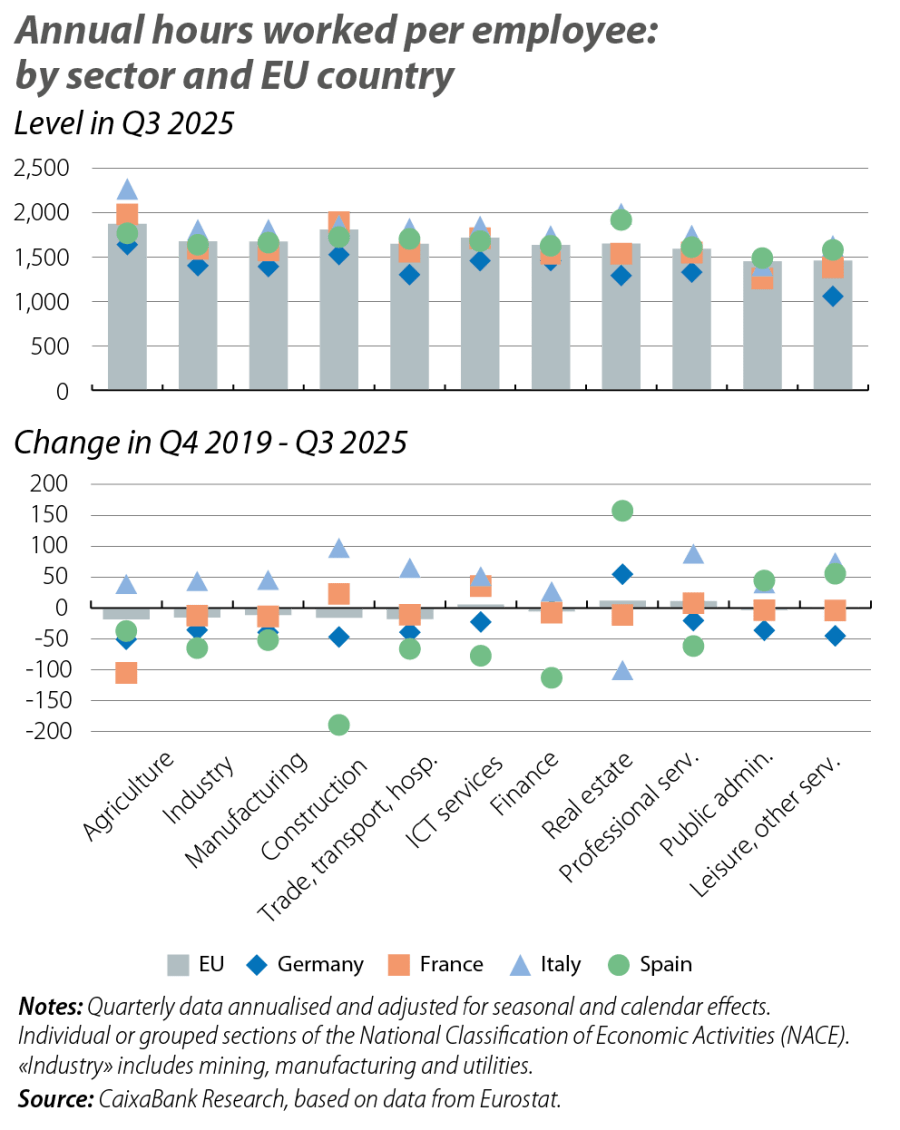

Fourthly, in the post-pandemic period, we note that the changes in the number of hours worked across different sectors are generally similar and moderate throughout the EU (see second chart). France shares the same diagnosis, while the reductions in Germany and the increases in Italy are equally widespread, albeit somewhat more intense. In Spain, however, the dispersion is quite pronounced, as we see a significant decline in construction (11% fewer hours worked in Q3 2025 compared to Q4 2019) and finance (a 7% decrease), in contrast to increases in real estate activities, public administration, and leisure and entertainment services.6

- 1

For the widespread increase in the intensive use of labour in Italy, refer to chapter 4 on the labour market in Ufficio Parlamentare

di Bilancio (2025), «Rapporto sulla politica di bilancio 2025». - 2

Bank of Spain (2023), «An analysis of hours worked per worker in Spain: trends and recent developments» and ECB (2025), «Who wants

to work more? Revisiting the decline in average hours worked». - 3

ECB (2023). «More jobs but fewer working hours».

- 4

See the second chart for sectoral differences in the number of hours worked. For an analysis of recent sectoral dynamics, see the Focus «Characterisation of the business cycle in the EU: neither widespread, nor robust» in the MR01/2026.

- 5

For this last factor in the case of Spain, see the Focus «The disparity between employment and hours worked in Spain» in the MR07/2024.

- 6

The strong negative correlation between hours worked in construction and real estate activities is striking, and this extends to

the EU as a whole and to the four major economies analysed here.

The complex relationship between hours worked and productivity

The academic literature documents a bidirectional but inconclusive relationship between productivity and working hours.7 On the one hand, efficiency gains can generate a positive income effect if they are associated with higher wages, which ultimately reduces the number of hours offered by a worker, but they can also lead to a greater substitution of leisure in favour of work if the former becomes relatively more expensive. On the other hand, conversely, a fatigue effect on productivity may occur due to a greater number of hours worked (diminishing returns), and this can coexist with the effect of a fixed cost of entry or of cumulative learning that boosts productivity in parallel with working hours. The prevalence of certain channels over others will be decisive in assessing the impact of specific events or economic policies.

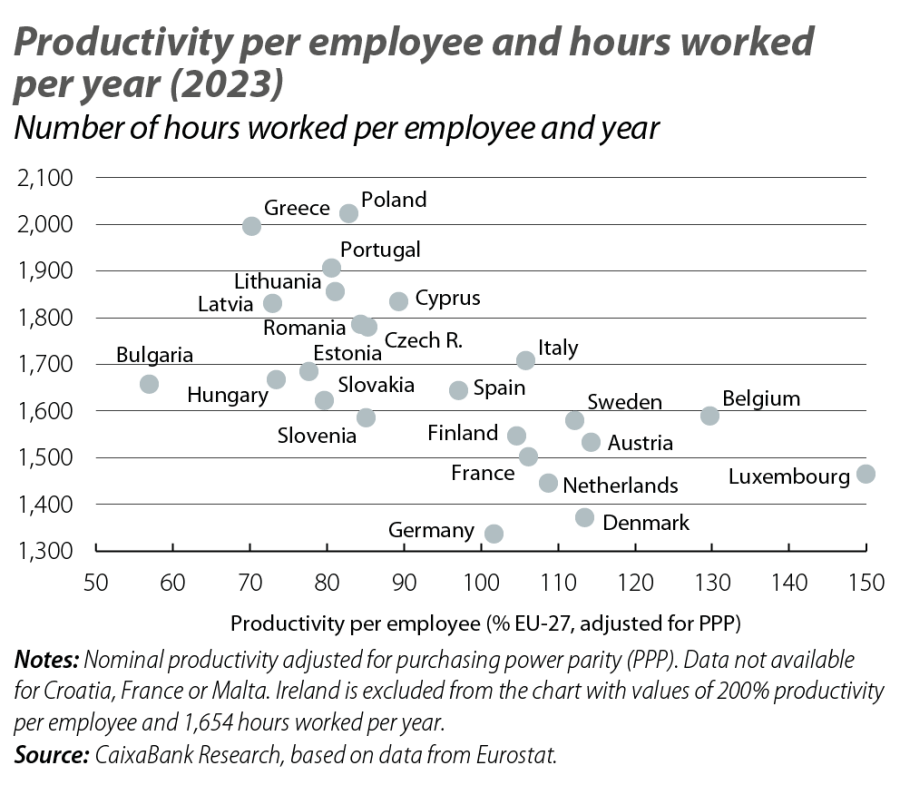

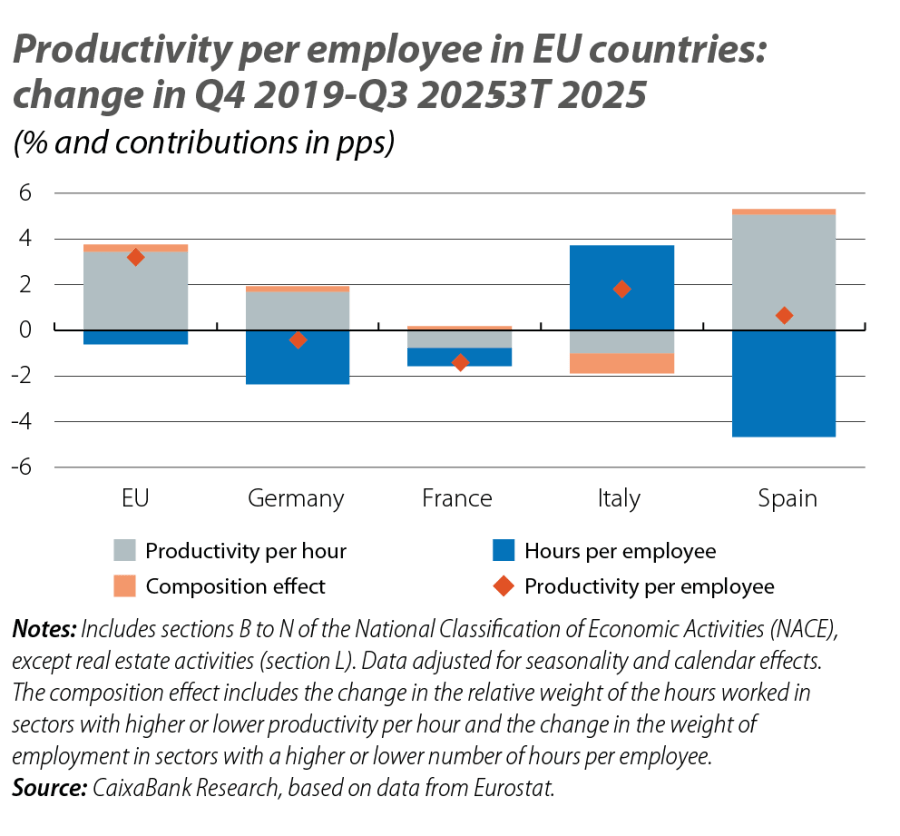

In the case of the EU, a long-term view reveals a negative relationship between economic development and the number of hours worked per employee (predominance of the positive income effect). Thus, in Eastern Europe, where working hours have significantly decreased in recent decades in parallel with the process of economic convergence with the founding members, the persistence of a high productivity gap8 coexists with figures still notably higher than the average (see third chart). More recently, for the EU as a whole, further reductions in the number of hours worked per employee in the post-pandemic period have been compatible with increases in productivity per hour and per employee, aided by a positive compositional effect towards more productive activities. However, this has not been the case for the four major European economies (see fourth chart). In particular, in the cases of Germany and Spain, there is a stark contrast between the reduction in working hours and the increase in productivity per hour worked, which has resulted in GDP per employee being practically stagnant over the last five years.

- 7

A good summary can be found in G. Cette, S. Drapala and J. Lopez (2023). «The circular relationship between productivity and hours worked: A long-term analysis».

- 8

See the Dossier «An analysis of European productivity» in the MR01/2026.

In summary, the reduction in hours worked in the EU is a secular trend that is likely to continue in the coming decades, supported by the ageing of the population.9 However, its intensity is not set in stone and will depend on a number of factors, including trends in productivity, regulatory changes in statutory working hours, the general health conditions of older workers, as well as incentives and policies aimed at increasing labour participation and part-time work.10 As for the role of productivity, a scenario in which the efficiency gains linked to artificial intelligence are limited or unevenly distributed will likely hinder further reductions in working hours if the current level of well-being is to be maintained.11

- 9

See the Dossier «Challenges and policies in the age of longevity» in the MR09/2025.

- 10

IMF (2024). «Dissecting the Decline in Average Hours Worked in Europe».

- 11

See footnote 7.