EU export diversification beyond Trump’s tariffs

Trade protectionism has been part of the new geopolitical normal for years now, but it has reached its peak in 2025 with the new US administration. In this more hostile environment and in the absence of an effective multilateral forum, the EU continues to make efforts to broaden its economic relations with different regions of the world. The strategy of diversification has become a valuable tool, not only in the search for markets with high export growth potential, but also in making progress towards the desired strategic autonomy.

In search of expanding markets

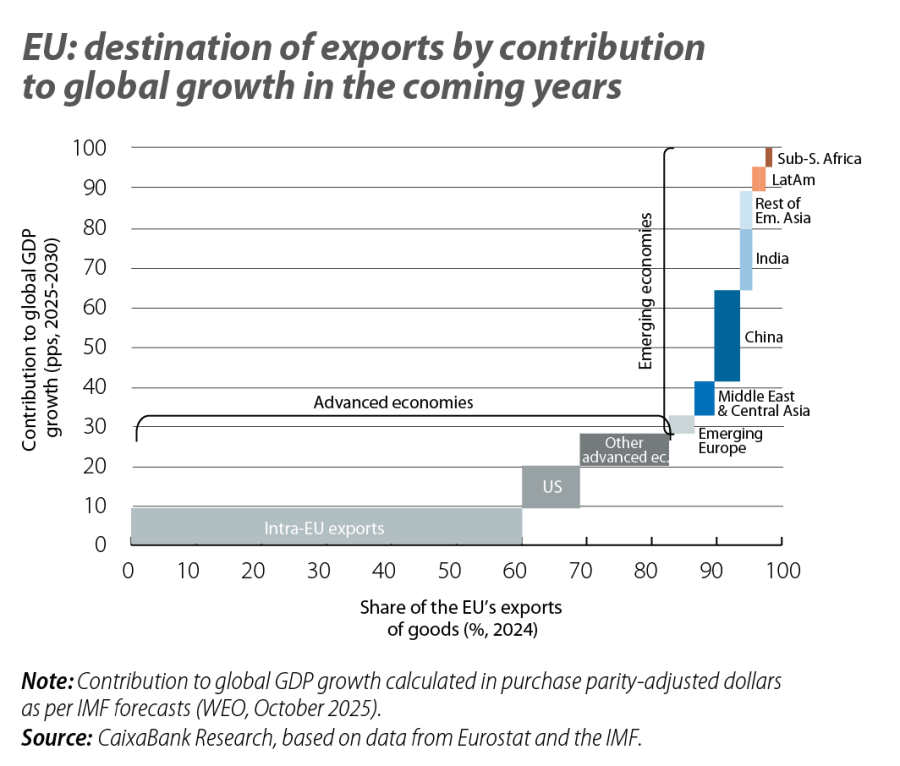

The main destination for EU countries’ exports remains predominantly other Member States (around 60% in 2024), which contrasts with the small contribution that this economic zone is expected to make to global growth in the medium term (less than 10% in the next five years) (see first chart). We find a similar imbalance between exposure and potential growth for other advanced economies, particularly those that are geographically closest and with which the EU has maintained historical and commercial ties for decades (the United Kingdom, Switzerland and Norway). The main exception among developed countries would be US, the only one of this group with which there is no trade agreement following the failure of the TTIP in the middle of the last decade, and for which its expected contribution to global growth exceeds the share of European exports (11% vs. 8%).

The situation is clearly asymmetric for emerging economies as a whole and for Asia in particular. According to forecasts up until 2030, China and India – also without any bilateral agreement – are expected to account for just over 40% of global GDP growth in the coming years, whereas they accounted for just 4% of the EU’s total exports in 2024. A similar situation is true for the set of ASEAN countries (among which the EU only has a trade agreement in force with Vietnam) and, to a lesser extent, for other regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, the Middle East and Central Asia. There is only a correspondence between export share and global economic relevance with the emerging countries located close to Europe, the main partner being Turkey, with which there has been a customs union since 1995.

Bilateral agreements to overcome multilateral paralysis

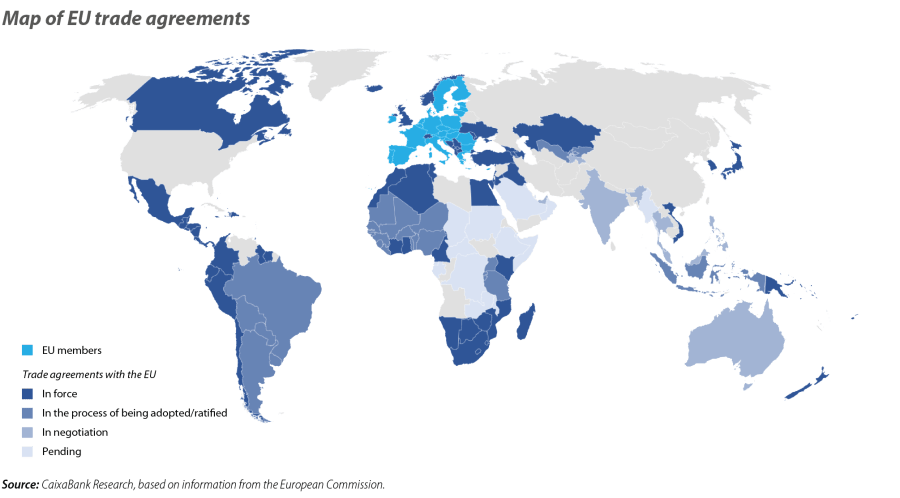

The Doha round of negotiations on trade began in 2001 and is by far the longest in history under the multilateral umbrella of the WTO. However, no meaningful agreements to continue reducing tariff and non-tariff barriers in the trade of goods and services were reached. In the absence of progress, countries have opted for a bilateral and regional agenda, and nearly 300 agreements of this nature have been signed in the world over the last two decades (compared to less than 100 in force at the beginning of the period). The EU has been no exception and has gradually expanded its economic relations beyond the European environment, with a total of 37 agreements coming into force between 2001 and 2025 (see second chart). Among the most relevant in terms of trade volume are those signed with Japan (2019), South Korea (2011), Canada (2017), Ukraine (2014) and Singapore (2019).1

- 1

The agreements with Canada and Ukraine are provisionally in force pending final ratification by Member States, while in the case of Singapore the EU continues to negotiate the specific agreement on digital commerce.

More recently, the EU has concluded successful negotiations with MERCOSUR (December 2024) and Indonesia (September 2025). The treaties are now awaiting ratification by the European Council and Parliament, as well as by the various Member States. In the case of MERCOSUR,2 as was the case in 2019-2020, France is the main opponent to its definitive adoption due to the competition is entails for agricultural products, a view shared by Poland and Ireland, while environmental aspects are fuelling the reluctance of Austria, Belgium and the Netherlands. In parallel, the EU is in ongoing negotiations with India, the United Arab Emirates, Australia and three other ASEAN countries (the Philippines, Malaysia and Thailand).3

The potential of diversification in the face of Trump’s protectionism

A key feature of the administration that emerged from the US election a year ago is undoubtedly its more protectionist trade policy. In the case of the EU, according to our estimates this has resulted in an increase in the average tariff for entry into the US market to 12%, compared to the 1% that was in force in 2024.4 In this scenario, European exporting firms are adopting different mitigation strategies, ranging from direct investment projects in the US to finding alternative destinations for their products.5

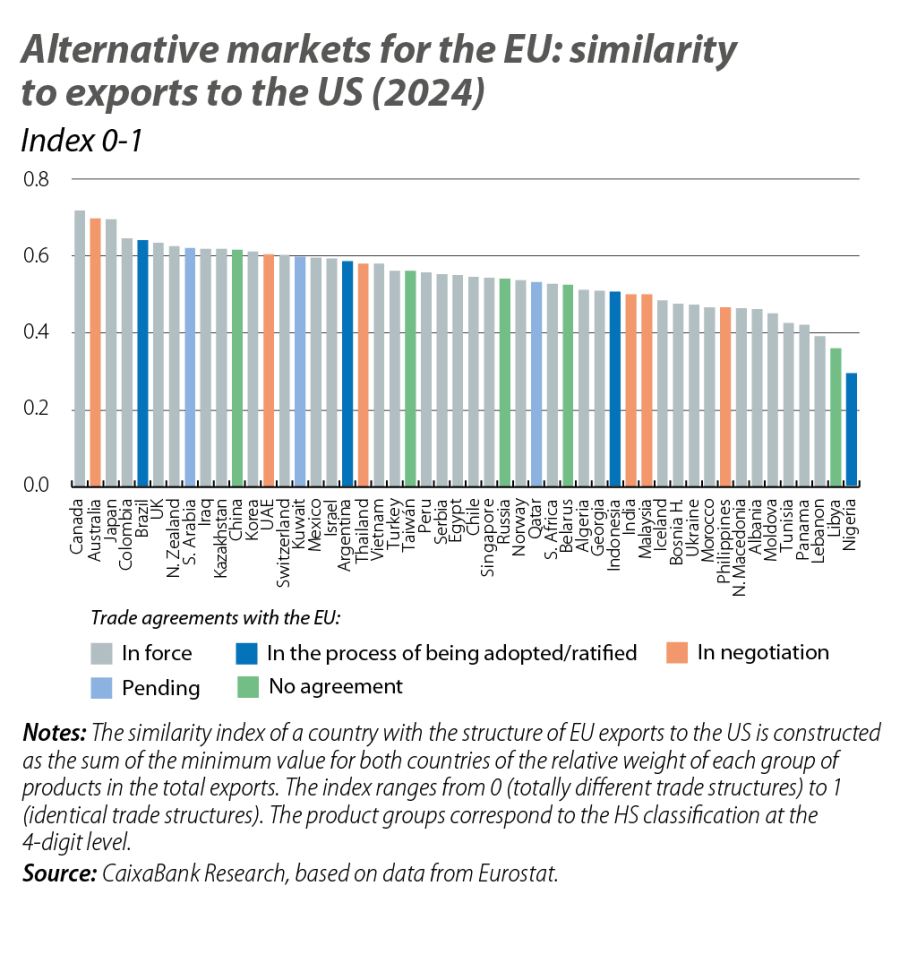

With regard to this second option, it is logical to assume that goods that are no longer sold in the US market will fit more easily into countries where EU exports have a similar product structure. According to the export similarity index,6 we estimate that the candidates for diverting trade from the US would be mostly developed countries, such as Canada, Australia, Japan, the United Kingdom and New Zealand, but also some Latin American economies, such as Brazil and Colombia (see third chart). Another important factor is the degree to which European products have access to these markets. Overall, this is positive, as the EU either has trade agreements signed with the aforementioned countries or the most-favoured-nation tariff is low compared to the rate now imposed by the US. The notable exception is Brazil, particularly for the entry of agricultural products.

- 4

The US-EU agreement reached in late July establishes a general entry tariff of 15% for European exports, with exemptions applied to a number of products, such as generic pharmaceuticals.

- 5

See, for the case of Spain, the article «Tariff tensions and reconfiguration of trade flows: impact on Spain», published in the Sectoral Observatory of the first semester of 2025.

- 6

See De Soyres et al. (2025), «The Sectoral Evolution of China’s Trade», FEDS Notes.

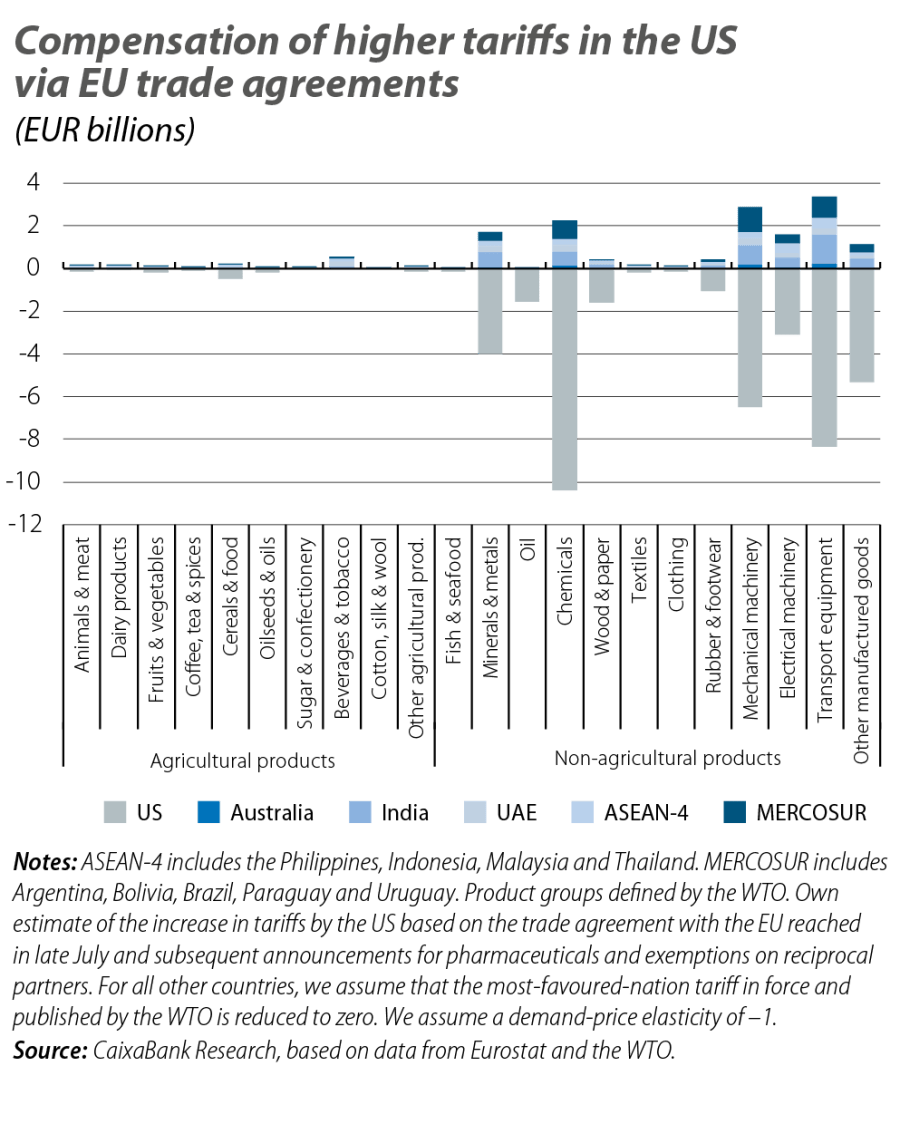

On this note, taking a more medium-term view, it is worth considering whether the EU trade agreements that are pending ratification and those that are currently being negotiated will be able to compensate quantitatively for the potential loss of the US market. For an initial approximation of the challenge that lies ahead, we can refer to the value of EU exports in 2024, when sales of goods to the US reached 530 billion euros, a figure that is more than double the sum of MERCOSUR, ASEAN-4, Australia, India and the United Arab Emirates combined (235 billion). A second, more precise estimate, in which we consider the response of imports of European products to the expected change in tariffs in each country (increase in the US and reduction in the rest), offers us a similar reading. Even in a scenario with a complete disarmament of tariffs with the new trading partners, these markets would cover just under 40% of what would be lost in the US (see fourth chart).7 By product group, the compensatory capacity would be lower for the chemicals, machinery and equipment industry, while the net balance could be positive in the case of agricultural products.

- 7

The compensatory effect does not change in relative terms for different values of demand-price elasticity, provided it is the same for all countries. What does change substantially is the magnitude of the challenge in aggregate terms, since with a unitary elasticity – which prevails in the short term – around 40 billion of exports to the US would be lost (8% of the total), while with a value four times higher – more reasonable in the medium term – this figure would be 175 billion (one third of the current level).

Export diversification should not only be a trade response to US protectionism, but a centrepiece for strengthening Europe’s strategic autonomy through reliable value chains. In a fragmented world, the EU needs more resilience, but this does not mean closing itself off. Agreements with new partners open up expanding markets, but they also broaden access to critical energy and mineral resources, as well as building partnerships for achieving global progress on key issues such as the green transition. That said, we must not forget that the greatest challenge remains within the EU itself. Making progress in the competitive structural agenda is essential to ensure that our most important trading partners – ourselves – do not continue to be the region contributing the least to global growth.