Factors shaping regional productivity disparities in Europe

In the second article of the Dossier «An analysis of European productivity», we review a broad set of variables covering institutional, geographical and technological aspects, as well as others linked to the economy’s productive fabric, in order to distinguish the different groups of European regions according to their productivity level.

Productivity is the ultimate driver of sustainable economic growth and long-term well-being. However, as we have seen in the first article of this Dossier («European productivity from a regional perspective»), neither its level nor its evolution over time are uniform across different territories, as they depend on multiple structural factors. In this article, we review a broad set of variables covering institutional, geographical and technological aspects, as well as others linked to the economy’s productive structure, in order to distinguish the different groups of European regions according to their productivity level. This framework serves as a prelude to the third article,1 in which we quantify their explanatory capacity relative to the dynamics observed over the last 20 years, seeking to understand why some regions have seen an acceleration in their productivity while others have stagnated.

- 1

See the article «Key factors driving productivity improvements at the European regional level» in this same Dossier.

The usual suspects explaining the geographical productivity gap

This section provides a brief overview of the aspects most frequently cited in the economic literature to explain territorial productivity differences and the transmission channels.

Firstly, institutional quality plays a crucial role. Regions with better governance tend to exhibit higher productivity and even enhance the returns of other factors such as training and innovation through regulatory efficiency, protection of property rights and the confidence of economic agents.2 Conversely, weak institutions constrain the development of human capital and R&D expenditure, as well as for their translation into efficiency gains. Institutional reforms can be slow, but they are crucial for development.

Secondly, geographical aspects have a significant impact. Densely populated and urbanised regions are conducive to agglomeration economies that boost productivity.3 The concentration of firms and workers facilitates specialisation, mutual learning, and more efficient services, while a high proportion of the population living in metropolitan areas tends to correlate with higher GDP per worker due to better access to markets and knowledge. Furthermore, neighbouring high-productivity regions increase the likelihood of a territory improving its relative position compared to others with a similar level of productivity.4

Thirdly, the structure of the regional productive fabric is a determining factor. A greater relative weight of the manufacturing sector tends to be associated with higher productivity and long-term growth, as it is in their industries – especially those with high technological complexity – where most innovation and efficiency gains are generated. Recent studies indicate that the relative decline of the manufacturing sector in European regions has been accompanied by a slowdown in productivity growth.5 Similarly, business size plays an important role. Regions where a significant portion of employment is in medium-sized and large firms – with greater capital, technology, and economies of scale – tend to be more productive than those dominated by microenterprises.6

Finally, technological factors are decisive in the regional productivity gap. A higher share of jobs in high-tech sectors (both in industry and in services) is associated with higher levels of productivity, as activities such as computing or electronics tend to provide high value added per worker. Similarly, R&D intensity has a positive impact by boosting efficiency and generating spillover effects that benefit the entire productive fabric of the economy. Several analyses have indicated that part of Europe’s low productivity growth in recent decades is due to a technological deficit compared to other advanced economies, including lower private investment in R&D, a lower dissemination of cutting-edge technologies and slower adoption of digitalisation.7

It is worth noting that these factors do not act in isolation but interact with each other. For example, good institutions enhance the positive effect of urban agglomeration or technological innovation. Similarly, skilled human capital is less likely to emigrate if the region offers a dynamic environment with attractive cities, cutting-edge sectors and good governance. The most prosperous European regions typically combine these ingredients virtuously, which explains much of the dispersion in productivity observed between territories.

- 2

A. Rodríguez-Pose, and R. Ganau (2022), «Institutions and the productivity challenge for European regions», Journal of Economic Geography, 22(1), 1-25.

- 3

A. Ciccone (2002), «Agglomeration effects in Europe», European Economic Review, 46(2), 213-227, and A. Gómez-Tello, M.J. Murgui-García and M.T. Sanchis-Llopis (2025), «Labour productivity disparities in European regions: the impact of agglomeration effects», Annals of Regional Science, 74(1), 123-146.

- 4

O. Aspachs Bracons, and E. Solé Vives (2024), «Evolución de la productividad en Europa: una mirada regional», Cercle d’Economia.

- 5

R. Capello and S. Cerisola (2023), «Regional reindustrialization patterns and productivity growth in Europe», Regional Studies, 57(1), 1-12.

- 6

See the Focus «Firm size and productivity gaps in the EU» in the MR10/2025.

- 7

IMF (2025), «Europe’s Productivity Weakness: Firm-Level Roots and Remedies», IMF Working Paper nº 2025/040 and R. Veugelers (2018), «Are European Firms Falling Behind in the Global Corporate Research Race?», Bruegel Policy Contribution nº 6.

Characterisation of the most and least productive European regions

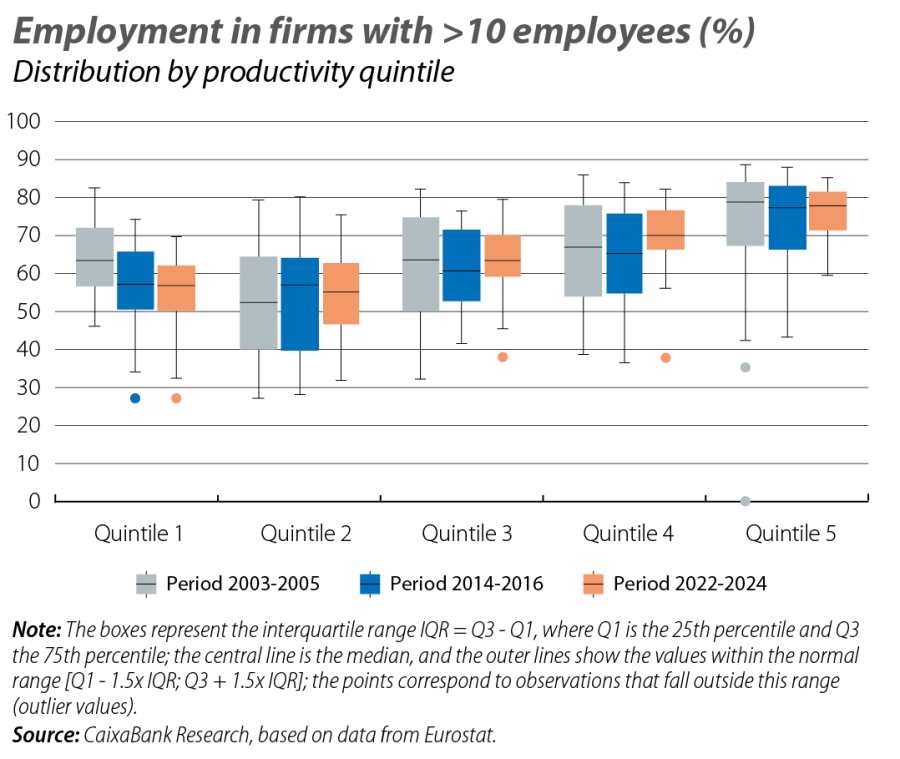

On the basis of the aspects identified in the previous section as relevant for explaining differences in productivity levels, we will now group Europe’s regions into productivity quintiles, differentiating them according to the value of the variables that represent institutional, geographical and technological aspects and those linked to the productive fabric (see the table for a description of the variables used and their sources).8

- 8

In this article and those that follow, the European regions correspond to the NUTS2 territorial analysis units according to Eurostat (autonomous communities in the case of Spain).

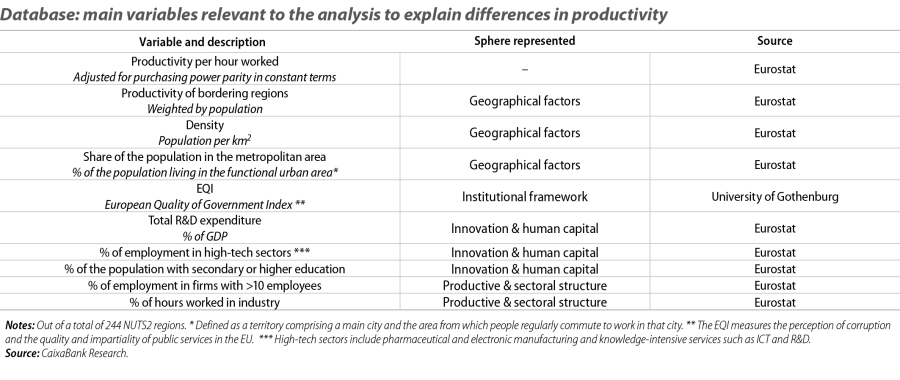

In the institutional sphere, we use the European Quality of Government Index (EQI) developed by the University of Gothenburg, which has been published every three years since 20109 and includes aspects related to the quality of public services and the perception of corruption. We observe that the most productive regions tend to exhibit significantly superior institutional quality, with good governance and effective public services (see first chart). This advantage has remained relatively stable over time, while the less productive regions show very limited improvements.

- 9

For 2003-2005, we take the value of 2010.

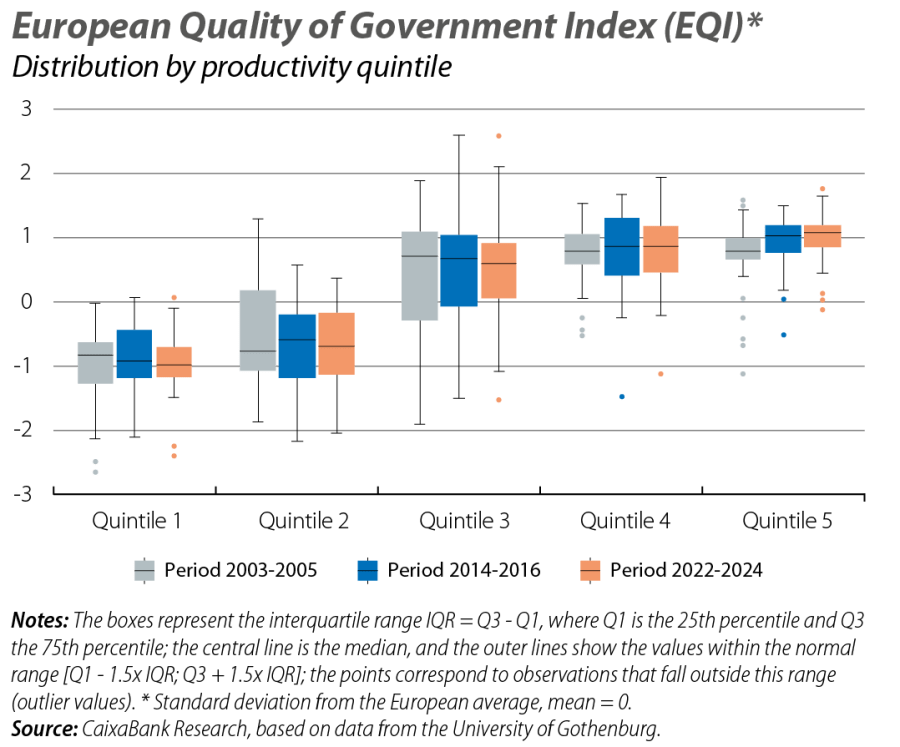

For the geographical dimension, we use three variables: population density, measured as the number of inhabitants per square kilometre published by Eurostat; the share of the region's population living in metropolitan areas, defined as functional urban areas;10 and the productivity of neighbouring regions, which we construct as a population-weighted average. The most productive regions coincide with large metropolitan centres, and this trend is reinforced over time. In less productive regions, urban growth is more limited, which hinders the generation of agglomeration effects. Something similar is observed in the case of density: it is higher in the regions that make up the most productive quintile. Finally, neighbouring regions can influence the productivity of each region through proximity to other markets, the possibility of cross-border cooperation, technological diffusion and access to shared infrastructure. The most productive European regions are also surrounded by highly productive regions (see second chart). In contrast, in less productive regions, the productivity of their bordering regions is also low. Throughout the three periods, a progressive improvement is observed in the upper quintiles, especially in those with the highest productivity (quintile 5), where the productivity of the bordering regions intensifies. This could reflect better economic integration, the utilisation of European networks and greater business dynamism. In the middle quintiles, the progress is more moderate, while in the lower quintiles there are hardly any advances, indicating persistent structural barriers.

- 10

A functional urban area is a zone comprising a main city and nearby municipalities that are connected to it, primarily on the basis of daily commutes, such as people going to work or to study; it is characterised by an urban centre, with high population and employment density, and a peri-urban crown, where people who work or study in the centre live. This concept is used by bodies such as Eurostat and the OECD to understand how cities and their surroundings are really organised, beyond administrative boundaries, and it helps in planning public policies, transport, housing, etc.

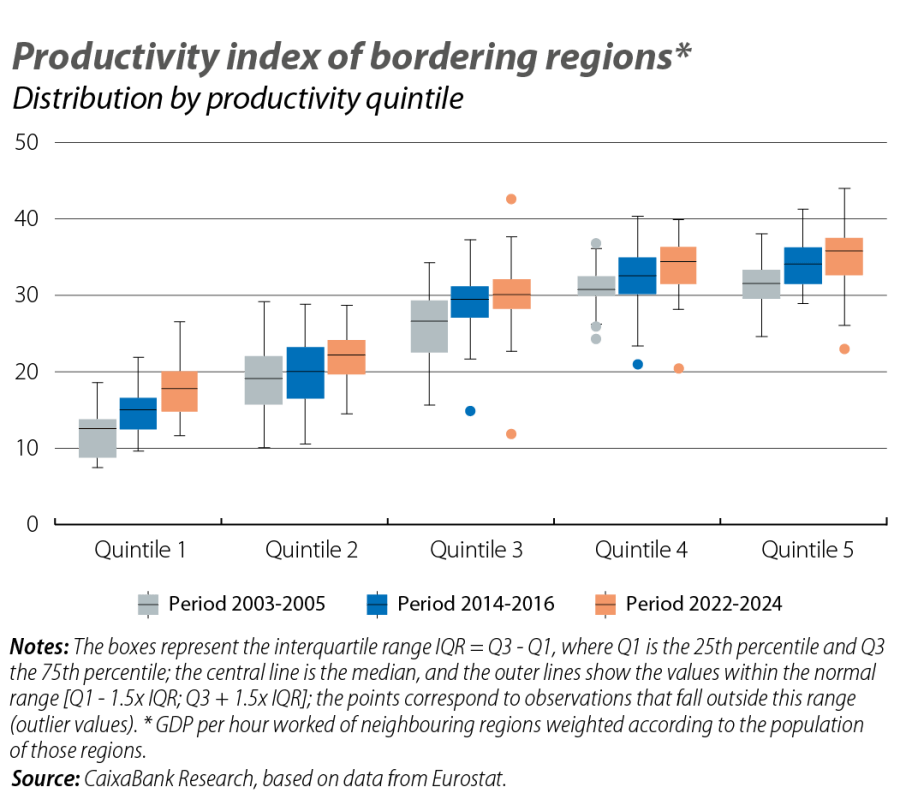

If we focus on the dimensions related to the business structure, the results are also noteworthy. Regarding the share of employment in industry, it is observed that this is higher for regions in the lowest quintile and then shows no clear pattern as the regions become more productive. This characterisation reflects the fact that Eastern Europe – with a good number of its regions at the lower end of the distribution – plays a significant role in Central European industrial value chains. On the other hand, the sector's role in the economy has steadily decreased over time, reflecting the progressive shift towards a service-based economy consistent with countries’ more advanced economic development. Also, the regions with higher productivity have a business structure that is made up of larger firms, specifically with a higher share of employment in firms of more than 10 workers; this suggests that more scalable firms have higher productivity, as has been empirically documented in the economic literature (see third chart). This difference persists over time, although the intermediate quintiles show some improvement. In less productive regions, employment in microenterprises predominates, which limits the ability to scale.

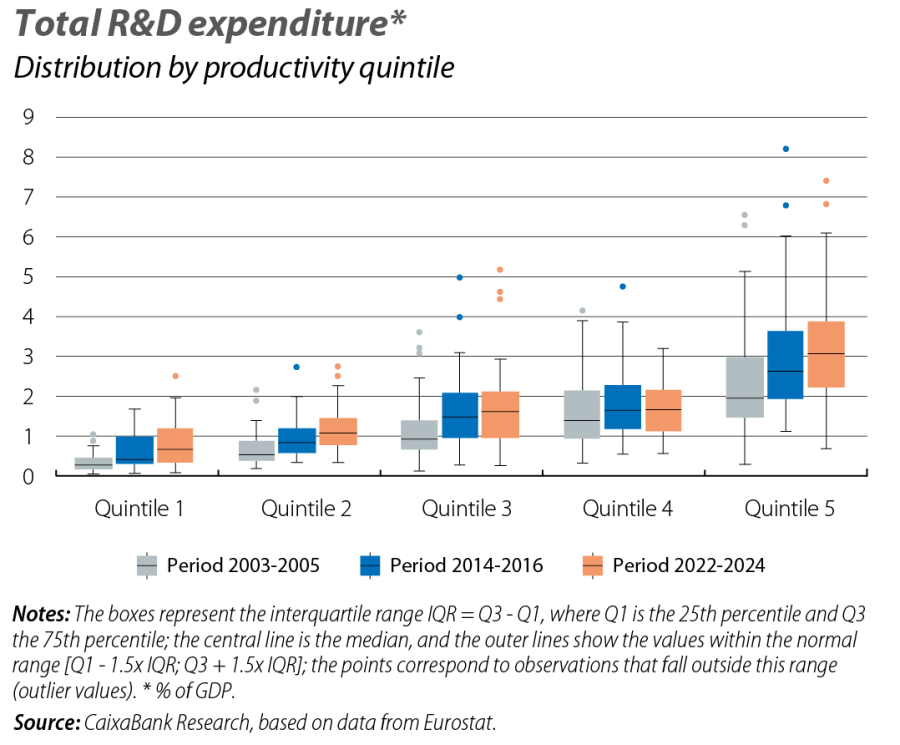

If we look at the variables of innovation and human capital, the relationship also goes in the expected direction. In all regions, the share of people with higher education has increased over the last 20 years, but it is in the most productive regions where this share is highest (the same applies to both secondary and higher education). Also, from the first period, it is observed that the most productive regions allocate a significantly larger proportion of their GDP to research activities, which enhances their capacity to generate endogenous innovation (see fourth chart). In contrast, the lower quintiles exhibit much lower levels, which limits their potential for technological convergence. This structural gap persists over time. A similar pattern is observed for the share of employment in high-tech jobs, as this share increases when we move towards more productive regions.

The visual evidence suggests that institutional quality, urbanisation and density, the productivity of the neighbouring environment, sectoral and business structure, human capital, and R&D intensity may be key determining factors of regional productivity in Europe. In the following article, we analyse to what extent the quantitative estimates confirm this hypothesis.