Will an ageing society pay lower interest rates?

In the other pages of this Dossier, we have analysed in depth how ageing will affect the capacity for economic growth and the public finances. All these changes will have consequences on the supply and demand for savings and, therefore, on the interest rates of economies.

From ageing to savings: transmission channels

We can divide the transmission mechanisms of population ageing on interest rates between those that affect the demand for savings and those that affect the supply. On the demand side, it should be borne in mind that population ageing goes hand in hand with a reduction in fertility and lower population growth. This results in less dynamic GDP1 and, consequently, investment: that is, lower demand for savings, leading to lower interest rates. In other words, as the capital of an economy slowly depreciates, the lower growth of the economy causes the capital stock-to-GDP ratio to rise and generates a relative abundance of capital, which pressures interest rates downwards.2

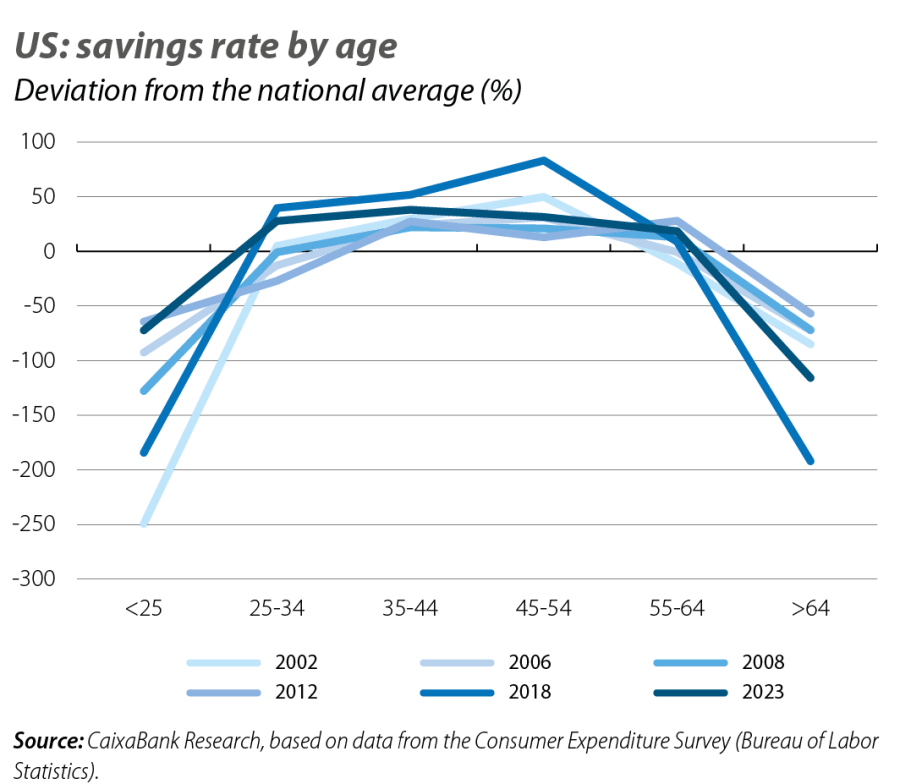

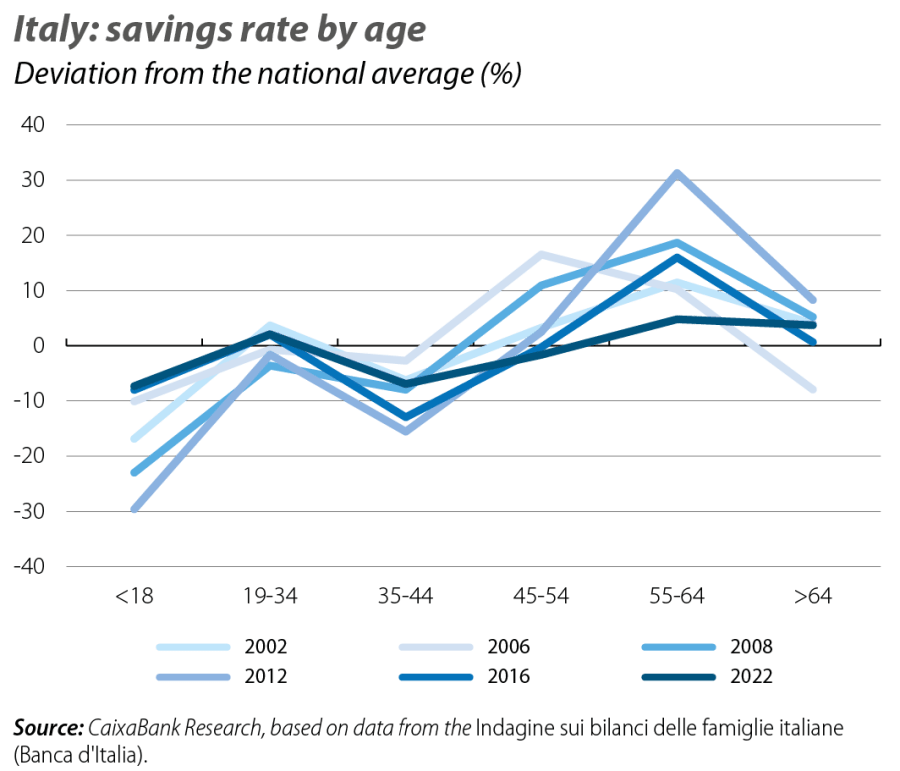

On the supply side there are different mechanisms, and all of them are derived from the so-called life cycle theory.3 According to this theory, the savings rate varies over the course of our lives following an inverted U-shape: young people and the elderly save less, while the middle-aged save more. The first chart shows how this relationship plays out in the US (not so clearly in Italy).4 The reason is the desire to enjoy a relatively stable quality of life over time. Thus, the life cycle theory suggests that people should save more at those ages at which they earn higher incomes, and use these extra savings to improve their quality of life in stages with a lower income flow (typically youth and old age).

- 1

See the article «The effects of ageing on growth and policy tools to mitigate them» in this same Dossier.

- 2

See C. Jones (2023). «Aging, secular stagnation, and the business cycle», Review of Economics and Statistics, 105(6), 1580-1595.

- 3

A. Ando and F. Modigliani (1963), «The ‘life-cycle’ hypothesis of saving: aggregate implications and tests», American Economic Review, 53(1), 55-84.

- 4

In Spain, according to internal CaixaBank Research data, there is also a clear inverted-U relationship between the savings rate and age.

Taking into account these fluctuations in savings throughout the life cycle, population ageing generates two major forces on the supply side. The first presumes a change in the behaviour of savers. Ageing is associated with an increase in life expectancy and in the number of years of labour inactivity after retirement. If people want to maintain a stable quality of life over a longer retirement, as the life cycle theory postulates, then higher life expectancy should spurt an increase in savings in the years of labour activity. That is, the increase in life expectancy ought to increase the supply of savings.

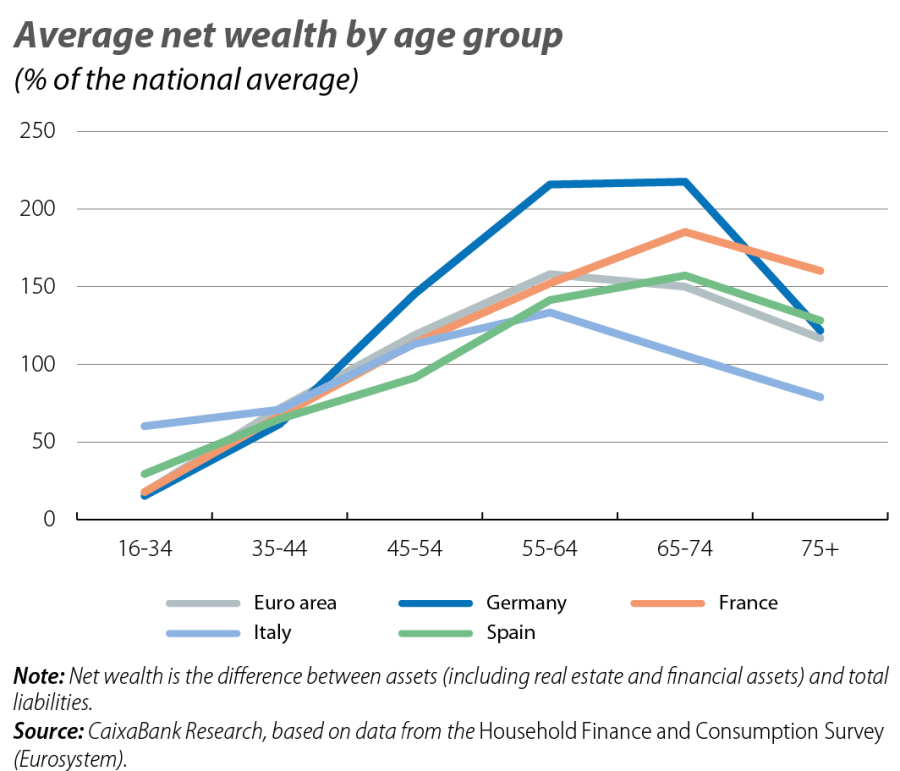

The second force is based on changes in the composition of savers. On the one hand, the increase in the elderly population means that a greater proportion of the population would be comprised of a segment which, according to the life cycle theory, should have lower savings rates. This dynamic depresses the total supply of savings. However, the third chart illustrates how the elderly population is, at the same time, a group that tends to have a larger stock of savings accumulated throughout their lives (whether in the form of real estate or financial assets) and, therefore, if the elderly population increases in relative terms, so too should the total supply of savings. Overall, changes in the composition of the population have an uncertain effect because they present two opposing forces: a flow effect (lower savings rate) and a stock effect (greater accumulated stock of savings).5

- 5

N. Lisack, R. Sajedi and G. Thwaites (2017). «Demographic trends and the real interest rate», Bank of England Staff Working Paper.

Finally, there is another mechanism that goes beyond the supply and demand for savings. Nominal interest rates also depend on inflation, since we usually talk about interest rates in terms of a currency, such as the euro or the dollar, and not in «real units». If population ageing makes the labour factor more scarce (for example, due to a reduction in the percentage of workers), then there could be more dynamic growth in wages and, therefore, in inflation, which would end up driving up interest rates in nominal terms.6 However, in the demographic transition there could also be disinflation if the loss of economic growth occurs more quickly than the reconfiguration of the productive structure (demand would lose steam faster than supply).

- 6

C.A.E. Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan (2020). «The great demographic reversal», Economic Affairs, 40 (3).

The net effect on interest rates

The mixture of mechanisms with different impacts on the supply and demand for savings and on inflation expectations prevents us from drawing unambiguous conclusions. While lower economic growth, higher life expectancy and the «stock of savings» effect tend to push rates downwards, the «flow of savings» effect and the traction between wage growth and inflation push them upwards.

One way of settling the net effect on interest rates is to build an economic model that contains all of the forces discussed as ingredients. This is what studies like those conducted by Auclert et al. (2021),7 the IMF (2023)8 and Lisack et al. (2017) do.9 According to all of these models, population ageing results, on balance, in lower interest rates. However, each model has its nuance. On the one hand, the IMF believes that, as the demographic transition is already at an advanced stage, its impact on interest rates in the future will be moderate. On the other hand, Lisack et al. (2017) emphasise the life expectancy channel (which will continue to progress) and still anticipate a significant downward pressure on interest rates in the 2040 horizon. In the same vein, Auclert et al. (2021) highlight the «stock of savings» effect and project persistent downward pressure through to 2050. A monograph by the ECB itself10 also estimates a persistent negative impact.

However, these results are not free of uncertainty.11 Beyond the particularities of each model, there is the question of how people’s actual behaviour will change. For example, a longer working life would ease downward pressures on interest rates. Also, the inverted-U relationship between the savings rate and age is still a theoretical postulate, and actual data show significant variation across countries and time periods, with some meaningful deviations from the theoretical postulates (compare the most canonical case of the US, in the first chart, with the deviations presented by Italy, in the second). In short, like in the rest of the articles of this Dossier, in the case of interest rates the key once again lies in which levers will be activated in order to manage demographic forces.

- 7

A. Auclert et al. (2021). «Demographics, wealth, and global imbalances in the twenty-first century», National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper.

- 8

IMF (2023). «The natural rate of interest: drivers and implications for policy», chapter 2 of the World Economic Outlook of April 2023.

- 9

See the reference in footnote 5.

- 10

C. Brand, M. Bielecki and A. Penalver (2018). «The natural rate of interest: estimates, drivers, and challenges to monetary policy», ECB Occasional Paper.

- 11

See the discussion in a previous article, «The demographic cycle of savings and interest rates», in the Dossier of the MR11/2018.