The 2028-2034 EU budget: An impossible mission?

Undoubtedly, the negotiation of the next budget will once again test the health of the European project, on which our strategic autonomy needed to address the geopolitical challenges that will continue to come from abroad will depend.

On 16 July, the European Commission presented its proposal for the 2028-2034 EU budget, kick-starting a negotiation process with the Council and the European Parliament that could continue through to the end of 2027. In order to give the EU genuine strategic autonomy, the next budget should pursue two key objectives: to revitalise European competitiveness – following the guidelines laid out in the Draghi report – and to address the challenges of global geopolitics, including increased trade protectionism and the commitments assumed within NATO. Achieving these objectives will require vast resources to be mobilised. However, the capacity of the private sector to do so is yet to be seen, while on the public side, it seems that it will fall on national budgets, which today have limited degrees of freedom. In short,

this will be quite some balancing exercise.

A cycle with new priorities

The Commission’s proposal for the next budget (Multiannual Financial Framework as termed in Brussels) puts the total volume of resources at close to 2 trillion nominal euros, which represents an annual average equivalent to 1.3% of the EU’s expected GDP between 2028 and 2034.1 This figure represents a quantitative leap compared to the previous budget, which amounted to just over 1.2 trillion euros (1% of the average nominal GDP for 2021-2027), although this was then reinforced by 800 billion euros of NGEU funds, of which the repayment of the joint debt issued to finance it would now absorb 168 billion. In addition, for the sake of simplicity and flexibility, the proposal entails a reduction in the number of thematic areas and EU programmes, as well as changes in their implementation, facilitating the reallocation of funds according to needs and including a transformation of structural funds (social and territorial cohesion, and agricultural policy) in the direction marked by the NGEU funds.

The focus of the funds has also been substantially changed in response to the strategic priorities review (see first chart). Some of the main innovations include the creation of a Competitiveness Fund allocated with a budget of 409 billion euros, which becomes the EU budget’s main vehicle for pursuing the investment agenda proposed by the Draghi report.2 The main recipients include the boost to innovation through the Horizon programme (175 billion) and the defence and space industries (131 billion), both with a significant increase over the 2021-2027 cycle, while the rest will be allocated to the clean transition, digital leadership and various bioeconomy sectors. These funds are complemented by a bigger budget for the Connecting Europe facility for trans-European transport networks (including military mobility) and energy networks (81 billion in total).

- 1

European Commission (2025). «The 2028-2034 EU budget for a stronger Europe».

- 2

See the Focus «A shift in the EU’s political priorities» in the MR04/2025.

As for other strategic areas, of particular note is the significant increase in resources allocated to international cooperation and support for EU candidate countries. Thus, the Global Europe instrument is bolstered up to 200 billion, while two funding lines outside the budget are proposed to cover needs linked to the war in Ukraine and the country’s future reconstruction (for a total of 131 billion). At the same time, funds for the management of migration, asylum and border control are increased (up to 74 billion). Finally, with emergency management such as COVID-19 in the forefront, the Commission’s proposal includes a new transitional lending mechanism which is allocated 395 billion – also outside the budget – for potential future crises, which would be in addition to other EU funds aimed at building resilience in the spheres of health and civil protection.

The eternal funding dilemma

The new Competitiveness Fund marks a step forward for leveraging a structural change in the European economy, but its impact is expected to be limited without a full Savings and Investment Union to mobilise the necessary private capital. This will be particularly important for financing innovative projects that can drive the digital transformation and lead to productivity gains, as well as for supporting the green transition with the formation of a European clean technology industry. On the other hand, the EU effort proposed in some areas, especially in defence, appears to fall short of the current investment deficits and the commitments assumed, suggesting that the public contribution will have to come largely from national budgets that are already under significant stress in most Member States (see «5% of GDP on defence: why? What for? Is it feasible?» in this same Monthly Report).

As in previous budget cycles, the debate over funding will remain intense up until its adoption. In contrast to the positions that demand the extension of the model used for the NGEU funds, with joint debt and non-reimbursable transfers, another group of countries is showing their usual reluctance, now reinforced given that the bill for those issues will absorb 8% of the total EU budget (24 billion each year). In short, although the combined fiscal space is wider than the individual one, with the consequent gains in terms of financing costs, Europe’s public finances are starting from a position with relatively high debt levels (87% of GDP in 2024).3 In this context, the Commission’s proposal provides for the possibility of using joint issues (up to 690 billion, somewhat less than NGEU), but only for the purposes of addressing certain contingencies (such as the new crisis mechanism) or for granting loans (either to Member States or to candidate countries, such as Ukraine).

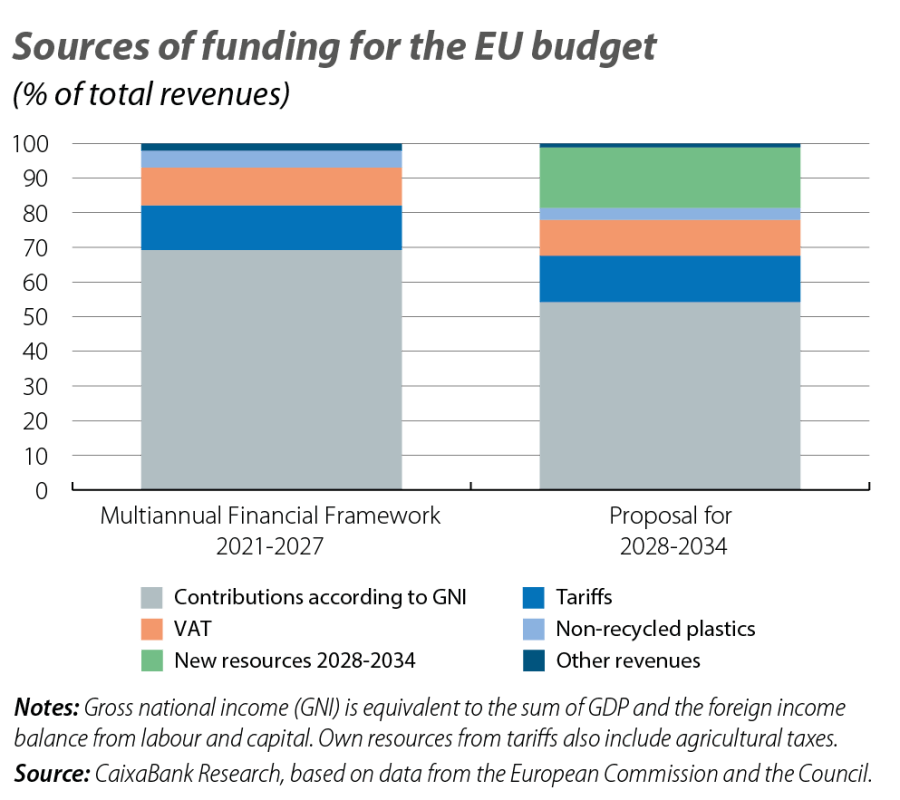

Another noteworthy element is the proposal to increase own resources by around 350 billion for the whole period 2028-2034, which would represent around 20% of total expected revenues (see second chart). These would come from different sources, including the Emissions Trading System (ETS) and the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), as well as new taxes on waste from unrecycled electrical and electronic equipment, tobacco and a fixed business contribution according to the level of turnover. Some of these new resources were already proposed in 2020 for the current budget cycle and were not adopted.

- 3

Includes 82% of GDP of national debt of Member States and 5% of GDP of pooled debt.

Cohesion and the green transition, key to the political negotiation

With regard to cohesion funds and agricultural policy (broadly including the environment and the climate transition), some voices point out that it is in these categories that the fiscal constraints and the EU’s new strategic priorities have been most clearly reflected. Thus, the nominal resources allocated for these policies are set to remain stable relative to the commitments for 2021-2027 (around 800 billion), but they would decline both as a percentage of the total budget (from 64% to 40%) and relative to GDP (from 0.6% to 0.5% per year, as shown in the first chart). This reduction contrasts with the stagnation of the last 15 years in the convergence between European regions, given the significant gap that persists between the most developed regions in the north-west and those with the lowest income per capita in the east, which still have large rural areas and an important role played by their agricultural sector.4 Moreover, a possible enlargement of the EU led by Ukraine would reinforce this diagnosis.

In addition to this quantitative change in the structural funds is the proposal for a significant adjustment in how they are governed. Following the design of the NGEU funds, the Commission envisages the development of National and Regional Partnership Plans (NRPPs) which will encompass the reform and investment programmes of each Member State and would provide access to the resources allocated in the EU budget. Criticisms of the role that local and regional governments will have in this new scheme indicate that this will also be a central element of the emerging political debate. Another component that is due to be inherited from NGEU is the availability of loans for implementing the measures set out in the NRPPs. The Commission proposes a total of 150 billion, which could potentially raise the total resources for cohesion and agricultural policy to levels equivalent to the current ones, albeit with the difference that these loans would increase the level of national public debt, whereas the EU budget essentially includes non-refundable transfers between Member States.

Last but not least, the search for support in the European Parliament and for consensus in the Council will also pivot on the new Commission’s apparent shift on the environmental and climate agenda. Criticisms point out that, despite the fact that the proposal maintains a target of 35% for EU expenditure in these areas, the follow-up of the commitments set out in the European Green Deal is lost, and the content of the measures seems increasingly subordinate to the competitive drive, with greater emphasis placed on supporting industrial decarbonisation and less on sustainable agriculture and biodiversity.

Undoubtedly, the negotiation of the next budget will once again test the health of the European project, on which our strategic autonomy needed to address the geopolitical challenges that will continue to come from abroad will depend.

- 4

European Commission (2024). «Ninth report on economic, social and territorial cohesion».