The challenge of America First for globalisation: threat or opportunity?

It is highly unlikely that the names Reed Smoot and Willis C. Hawley will be familiar to the contemporary reader, and yet the 1929 law that bears their name brought about the mass introduction of tariffs on some 20,000 products imported into the US. While the world was left astounded at how a stock market crash gave way to an unexpected fall in economic activity, the reaction of most countries to the Smoot-Hawley tariff was to respond with their own tariff measures. All this contributed to turning a recession that could have been «normal» into one which became extremely harmful. A few years later, the Second World War gave the final blow to the international system.

Out of its ashes, and under the undisputed leadership of the US, the current architecture of global governance was erected, known as the liberal international order: a set of rules and values embodied in a series of institutions whose ultimate goal was to ensure macroeconomic stability at a global level. Thus, after the Second World War, a set of economic and financial institutions were created (the IMF; the World Bank; the GATT, which was the predecessor of the current World Trade Organization; and the first incarnation of the future OECD). At the same time, other institutions were converted (the Bank for International Settlements) and new projects were sponsored (such as the EEC, which would lead to the current EU). These institutions and projects gave form to a common framework of shared values. This framework included a number of beliefs, such as that exporting, importing and investing should not be driven by countries’ political power, that the growth of different countries was not a zero-sum game, and that property rights should be protected (including intellectual property rights, a requirement for the international dissemination of knowledge). Incorporating these values into good practices required many elements. These included ensuring that the system provided common mechanisms for conducting international trade and financial transactions, ensuring that there was a virtually universal currency conversion system, and defining mechanisms to establish, calculate and control tariffs and customs rules, to name just the most essential aspects. In addition, the system defined institutions and methods for resolving differences between the partners (commercial differences in particular), it established technical harmonisation mechanisms and it offered protection schemes against certain risks (of a natural, macroeconomic and financial nature), ranging from emergency humanitarian aid to the exceptional provision of liquidity among central banks.

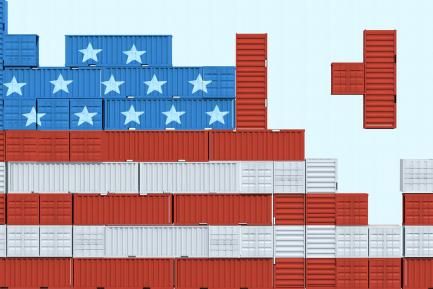

Well, all this institutional architecture is now being challenged. By whom? Paradoxically, by the founding partner, the US. Under the slogan America first, the current US Administration has embarked on what appears to be a profound rethinking of the world liberal order. Whereas the US’ international strategic approach to date has been multilateral and based on compliance with rules, it now appears to want to establish a bilateral philosophy, analysing each case from a cost-benefit perspective (in economic terms, but also political).

Let us go over what has been proposed to date, although this is an area which is constantly evolving and perhaps, when the reader reads this article, new measures may have been announced. From the very beginning of the new Administration, the US has abandoned the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), it has withdrawn from the Paris Agreement on climate change, it has chosen not to renew its participation in the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty with Iran (reimposing sanctions instead), it has begun an ambitious (albeit somewhat unrealistic) review of NAFTA and it has cast doubt, if not over NATO itself, over its military and financial commitment with the alliance. Furthermore, it has questioned the World Trade Organization and has left the United Nations Human Rights Council.

This litany of decisions has been accompanied by a progressive threat (and, in some cases, the actual implementation) of imposing tariffs on imported goods. In January 2018, the US applied tariffs to imported washing machines and solar panels. Shortly afterwards, in March, it announced its intention to apply tariffs on purchases of steel and aluminium, as well as on a wide variety of Chinese products. In addition, on various occasions it has threatened to impose tariffs on cars, and even on all Chinese imports. If these two measures were to be implemented (tariffs on cars and on all Chinese imports), a situation which seems unlikely (although nothing can be ruled out entirely), the average tariff of the US would go from 1.7% to 6.5%, a level not seen since the early 1970s. At present, and in response to the tariffs applied, the US’ trading partners have begun to respond by establishing similar measures: since the beginning of July, Canada, Mexico, the EU and China have already applied tariffs on some of their US imports to compensate – partially for the time being – the new tariffs imposed by the US.

Could these skirmishes (calling them a trade war is still debatable) mutate into something more serious and end up damaging global growth? A shock of this kind would affect growth in two ways, one direct and the other indirect. The direct impact would come in the form of a reduction in trade flows, disruption to global supply chains and higher prices of imported goods. The indirect impact would materialise in the deterioration of business and consumer confidence and in the tightening of financial conditions.

The quantitative exercises that have been undertaken tend to confirm that, if protectionism remains at current levels, or even slightly higher, its impact on global growth should be contained. But the situation would change if the level of tariff protection were to increase significantly (at the high end of the tariffs threatened by the US Administration). According to calculations by CaixaBank Research, using estimates provided by the Bank of England as a starting point, a 10-pp increase in tariffs between the US and its trading partners lasting for three years (2018-2020) would reduce global growth, over the same period, from the expected annual average of 3.9% down to 3.2%. This decline, which is rather significant, would be mostly driven by the direct impact, which would affect growth approximately twice as much as the indirect impact. However, we must not lose sight of the fact that the indirect impact can take various forms, some of which are potentially very harmful to growth. This being the global impact, the US would be particularly affected, since its average annual growth currently expected for the period 2018-2020, of 2.5%, would be reduced to a meagre 1.1%. The euro area, meanwhile, would suffer slightly less, growing by 1.4% in the event of a trade shock compared to the 2.0% expected today.

To reiterate the point, this represents an adverse scenario for the global economy. The levels of tariffs resulting from the aforementioned 10-pp increase would result in a situation similar to that last seen in the early 1950s, when the GATT had just started to remove tariffs. But even if the situation does not reach this level of severity and the short-term impact ends up being relatively limited, this does not mean that the consequences for the global institutional architecture in the medium and long-term will not be significant. One way to explore this terra incognita is to develop scenarios that integrate some of the essential features of the international system, as well as its players, which are currently in flux. Let us delve into the future by taking ownership of the US Administration’s slogan, as if under a small license, to offer three different visions of what might lay ahead.

Globalisation first. Let us imagine that the risks associated with the current situation are read properly and governments react accordingly. Now let us jump ahead a decade; what would we see? One possibility is that we would be decisively entering into what historians of the future would call the third wave of globalisation (after the first, which succumbed in the 1930s, and the second, which hypothetically ended with America First). The renewal of globalisation would have come at the hand of profound changes in the way in which institutions operate, giving a bigger voice to the new global powers (China, as well as other medium-sized powers such as Russia, India and Brazil) and opening up the agenda to new areas of globalisation. These would include the development of the agricultural sector (long-neglected demand from Africa and other exporting regions), alterations to financial globalisation (which enhances international coordination) and an intensification of trade in services (demanded by the advanced countries). The institutional reform should also allow them to resume their role as a forum for resolving competition issues and to effectively defend intellectual property. This renewed globalisation would also be more sustainable, incorporating solutions to the main sources of instability of previous years by finding creative ways to compensate those perceived as the «losers» of globalisation, whether citizens or countries. All this should allow the populist agenda to lose its grip. In this scenario, the world order would continue under the political and economic leadership of the US, but it would be a far cry from the unipolarity that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall.

America first, America out. Here we are moving away from win-win scenarios in which everyone benefits. One possible story would be as follows. As a result of the America First strategy and what earlier we have referred to as cost-benefit bilateralism, the US will have intensified its isolationist shift, an ever-present temptation in American foreign policy since the 19th century. The rest of the world, however, would not go down the same path: when dealing with the US, other countries would have little choice but to conform to the bilateral logic, but in all other cases globalisation would continue and its economic roots would remain deep. In its final stage, this scenario implies that a modified version of today’s globalisation would continue to operate, albeit on a smaller scale. In order for this to be a success, the problems mentioned above (essentially institutional and redistributive problems) would need to be solved, probably with solutions set out in the first scenario mentioned above. Given that the isolationism of the US would imply a more-than-likely decrease in prosperity and, by extension, in the US’ economic weight, under this scenario the system would swing towards a more pronounced multipolarity. This would involve a larger number of key players, possibly with China at the helm and probably followed by the EU as defenders of the new globalisation, as well as a myriad of medium-sized powers. The main complexity with this scenario is the transition from the current situation towards the new balance. At the end of the day, when it comes to international relations, history reminds us that wanting something is not the same thing as being able to implement it. In the 1930s, the only country with the capacity to exercise stabilising leadership was precisely the one that did not wish to do so, while the country which tried did not have the capacity to do it (the reader might have guessed that we are talking about the US and the United Kingdom, respectively). The complexity of the transition would be intensified by the need to implement a profound change in how the current form of globalisation operates. This would range from the reconfiguration of global production chains on a different scale, to the capacity to substitute the fundamental role of the US in the field of financial globalisation.

America first, Europe First, China first. In this scenario, the central element is the fragmentation of the global economic and political systems. To capture the essence of the scenario, we can think of a mercantilist form of globalisation in which each centre (the US, Europe and China) would integrate with its natural hinterland, accompanied by certain regional champions such as Brazil or India. Although this option might seem suboptimal but not disastrous, the truth is that it would lead to a clearly less efficient economy, on a smaller scale and with an even more complex transition process than the previous scenario. In addition, as happened with the historic phases of mercantilism of the 17th and 18th centuries, it would be a somewhat unstable system with a tendency for confrontations to arise between the different blocs.

Do these distant scenarios sound implausible, or perhaps overly dramatic? Of course, they have to be. All of us are children of a long period of prosperity and peace, and to think of sacrificing one of the key instruments of this result, the liberal institutional order, seems incomprehensible. For the common good, we must trust that the threats that are currently looming over globalisation result in a constructive process, leading to an enhanced and more sustainable version of the phenomenon. Not in vain, and on this point the consensus of economists is virtually unanimous, free trade is the most powerful tool for creating global prosperity that exists. Defending it, which does not mean sanctifying it but rather ensuring that it reaches its full potential, requires reform of the institutional system that protects it and improving the balance between the winners and losers of globalisation, even if this means giving minimum satisfaction to demands that are not always well founded. But renovating the building is very different to demolishing it, as the fateful history of the Great Depression reminds us. In 1930, they were well-aware that the Smoot-Hawley tariff was going to be a death sentence for future prosperity: in May of that year, 1,028 American economists signed a declaration calling for the policy to be vetoed. It was to no avail. Repeating the past is sad, but repeating errors of the enormity of those mentioned here is unforgivable. It should not happen.

Àlex Ruiz

CaixaBank Research