Emerging economies: resilience after three global shocks

We review how emerging economies have dealt with the pandemic, the crisis stemming from the war in Ukraine and the protectionist shift of the United States, and to what extent they have recovered.

Emerging economies1 have faced three major global shocks in recent years: the COVID-19 pandemic, the energy and food crisis stemming from the war in Ukraine, and the protectionist shift spearheaded by the US. The effect of these episodes has manifested itself in different ways among this group of countries. However, despite their magnitude, many emerging economies have shown remarkable resilience in terms of economic stability

and their capacity to recover.

From a macroeconomic perspective, the pandemic marked a sharp contraction for the global economy. The drop in incomes, rising unemployment and the increase of fiscal deficits and public debt meant a decline in GDP of 2.1% in 2020 for emerging countries, representing a fall of 6.7 pps compared to pre-pandemic projections. However, the recovery was faster than expected and the subsequent structural after-effects were largely alleviated as the negative impact on productivity was less persistent compared to previous events.2 With the war in Ukraine, the second shock was triggered in the form of an energy and food crisis, which led to a rise in inflation worldwide. In the case of emerging countries, inflation reached around 10% in 2022. Although the spike in prices affected these countries unevenly, it was3 energy and food importers that were the hardest hit, with significant increases in their current account deficits. This situation was further exacerbated by a synchronised tightening of monetary policy at the global level, which led to an increase in debt servicing for emerging countries.

The third shock, which we could date from Donald Trump’s victory in the US presidential race, has been triggered by the country’s protectionist shift through the introduction of widespread general tariffs, as well as specific tariffs on imports of key sectors such as semiconductors, energy and the automotive industry, among others.4 However, the global economy, and emerging economies in particular, has performed better than expected during the first half of the year thanks to imports being brought forward (ahead of the introduction of the tariffs), the gradual nature of the tariff hikes (which has prevented a trade war) and the easing of financial conditions in most countries.

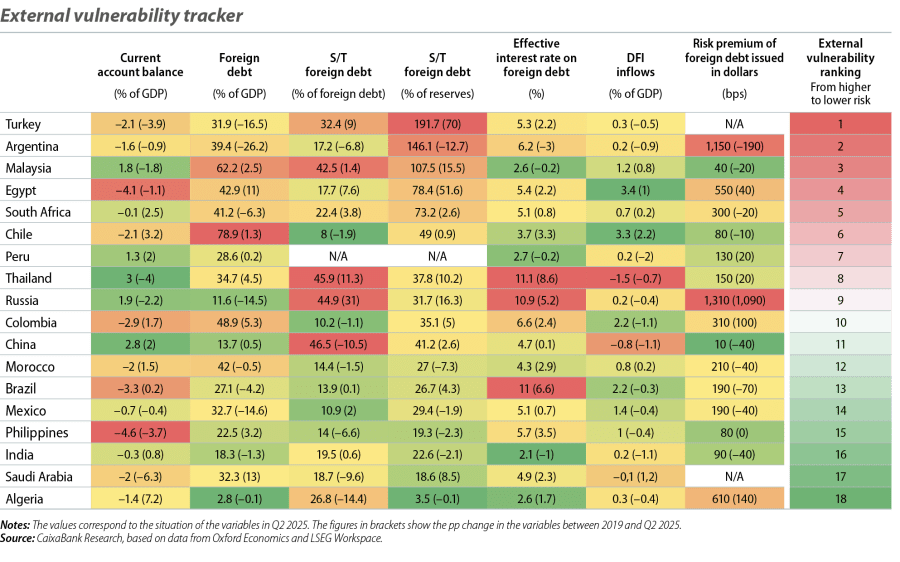

In addition, over the course of these five years, the resilience of emerging countries has been observed in other variables, such as the gradual recovery of the current account balance and the ratio of foreign debt to GDP, as indicated by our external vulnerability tracker.5 In short, this favourable progression has led many international organisations to improve their growth forecasts for emerging countries as a whole, including the IMF, which has revised its GDP growth forecasts6 for this year upwards on two separate occasions, placing them at 4.2% for 2025 and 4.0% for 2026 (+0.5 pps and +0.1 pp compared to the April forecasts, respectively).

- 1

The IMF considers emerging economies or markets to be those developing countries that show significant economic growth, accelerated industrialisation and growing integration into the global economy. The countries that form this group are: Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Colombia, Chile, Peru, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, South Korea, Vietnam, Philippines, Thailand, Taiwan, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, South Africa, Nigeria, Egypt, Kenya, Poland,

Czech Republic, Turkey, Russia, Hungary and Romania. - 2

See C. Jackson and J. Lu (2023). «Revisiting Covid Scarring in Emerging Markets», IMF.

- 3

See M. Lebrand, G. Vasishtha and H. Yilmazkuday (2023). «Energy price shocks and current account balances, evidence from Emerging Market and Developing Economies», World Bank.

- 4

See E. Kohlscheen and P. Rungcharoenkittul (2025). «Macroeconomic impact of tariffs and policy uncertainty», BIS Bulletin 110.

- 5

See the Focus «A first assessment of the external vulnerability of emerging market economies» in the MR10/2023.

- 6

See IMF. «World Economic Outlook, October 2025: Global Economy in Flux, Prospects Remain Dim».

Ingredients for the improvement in financial resilience

In addition to various economic factors, there have been some fundamental changes that have gradually cushioned the negative impact of each shock on emerging economies.7 COVID-19 marked a turning point in a large number of emerging countries, with more decisive decision-making and actions in monetary and fiscal policy.

On the one hand, many monetary authorities responded rapidly and decisively to the surge in inflation triggered by the disruption to global supply chains following the pandemic. Indeed, in the case of Brazil, Mexico and Russia the response was even ahead of the Fed and the ECB. This response marked a shift towards a stronger monetary framework, guided by the goal of anchoring inflation expectations and reducing dependence on exchange rate interventions. Moreover, autonomy in decision-making has boosted these central banks’ credibility.

On the other hand, in fiscal matters, the introduction of budgetary rules, despite the variations from country to country, and the fact that the fiscal consolidation process was initiated earlier than in previous crises, have provided relative fiscal stability in the emerging bloc. However, as the IMF points out, there is still a lot to be done in this area. It has been observed, for example, that despite the existence of fiscal rules in some Latin American countries, there have been fiscal deviations that have led to increased debt vulnerability.

- 7

See «Chapter 2: Emerging Markets resilience: Good luck or Good policies», World Economic Outlook, October 2025: Global Economy

in Flux, Prospects Remain Dim.

Capital flows, less volatile and more selective

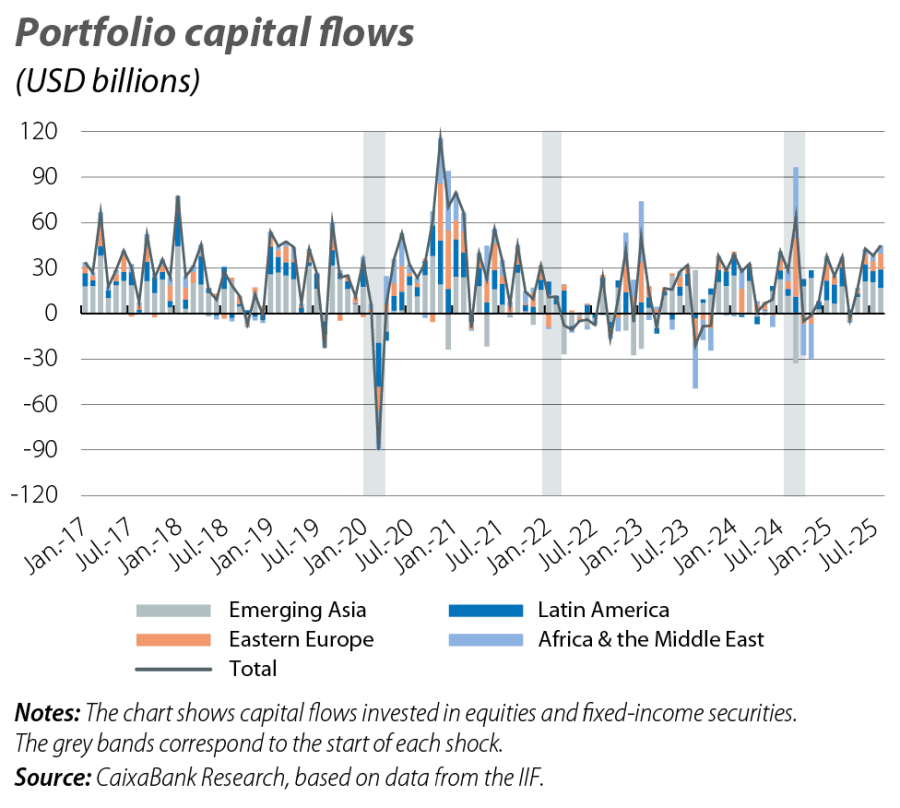

The outcome of the progress made in both the monetary and the fiscal spheres has been essential in building resilience in emerging countries. This strength has been reflected through one of the key aspects in the global scenario: capital flows.

Historically, emerging financial markets have been more vulnerable to global shocks. Typically, such shocks triggered a risk-off movement among global investors, characterised by the outflow of capital from these markets, the depreciation of their currencies and the tightening of domestic financial conditions (used as a tool to cushion the increase in the cost of foreign debt). However, the post-shock experience of recent years offers a different, more favourable reading from the traditional one.

As the IMF points out,8 those countries whose central banks have shown greater autonomy and have done a better job of anchoring inflation expectations have also reduced the need to intervene in their currencies. Similarly, early fiscal consolidation has contained sovereign risks, moderating spreads and facilitating access to external financing.

In addition, the efforts of many of these economies to build credible and stable institutions and policy frameworks have favoured the development of local currency markets in which, besides attracting foreign investors, a growing number of domestic investors are participating – an important component in sustaining the growth of these economies and reducing episodes of financial instability. According to the Institute of International Finance, August saw net capital inflows amounting to 45 billion dollars entering emerging countries, with a notable increase in debt denominated in local currency.

However, the recovery has not been even across the board. In a scenario like the current one, marked by geopolitical tensions, trade uncertainty and monetary divergence, investment flows have been concentrated in countries with solid fundamentals or those less exposed to Trump’s tariffs, while in others we see capital outflows or erratic patterns of behaviour. For instance, these flows have been sustained in countries such as Brazil, India, Peru, Chile and South Africa. In contrast, countries like Mexico, Argentina, Turkey and Colombia have been subject to greater volatility.

- 8

See footnote 6.