India vs. China: a growth perspective

India and China have undergone an unprecedented economic transformation in recent decades, but their growth trajectories have followed diverging paths. In this article, we compare the two models from a long-term perspective, breaking down the factors that have driven their economies: capital, labour and productivity.

The rise of India and China as economic powers has been one of the most profound changes in the global economy in recent decades, unravelling a landscape previously dominated by advanced economies. In a previous article,1 we explored the role that India could play in the global economic order, highlighting its rapid progress and good medium-term growth prospects. However, India is at a different stage of development than China. To understand the differences in its development, we will adopt a long-term growth perspective, with the aim of identifying the factors that have driven the Indian economy and the root causes of its divergence with China.

- 1

See the Focus «India: the wheel of dharma on the path to development» in the MR05/2025.

The wheel of dharma and its steering shafts: capital, labour and productivity

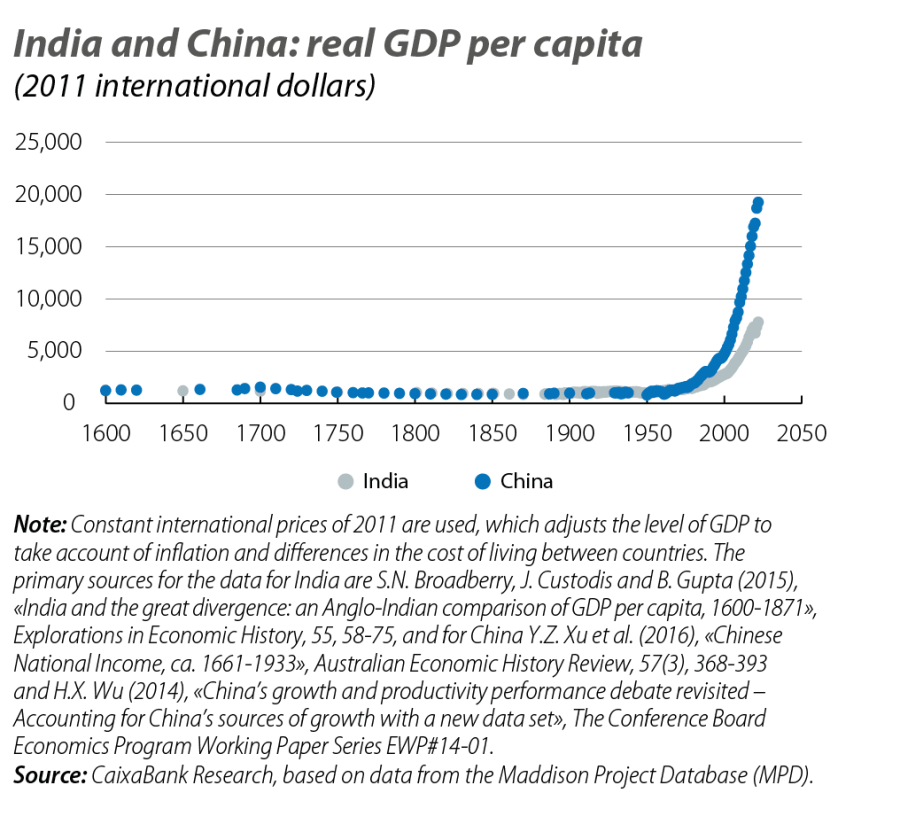

Up until the 1970s, India and China shared similar income levels. Despite very different historical trajectories, the GDP per capita of the two countries was around 1,400 dollars (at constant 2011 prices), far behind other economies such as Japan (15,000), South Korea, the Philippines or Thailand (3,000). Beginning in the 1980s, however, their growth paths diverged significantly – an evolution that has been the subject of extensive debate.

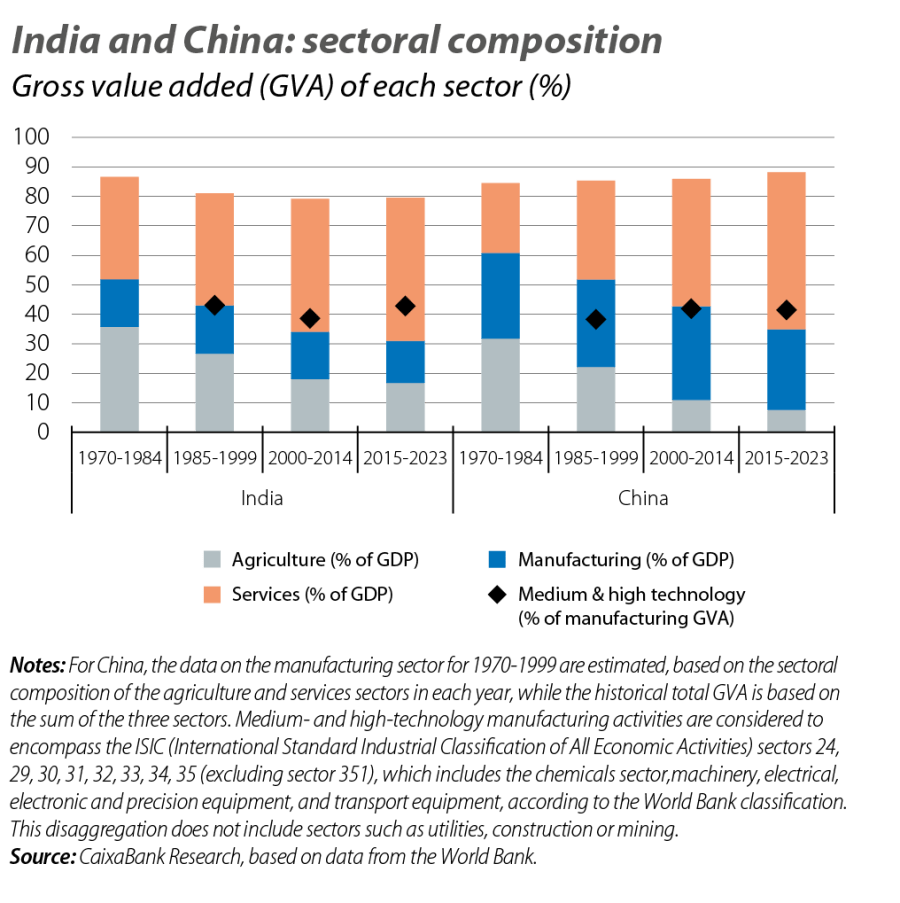

The two countries share characteristics such as a vast territory, a large population and accelerated economic growth in recent decades (China’s GDP increased 10-fold in 40 years and India’s 5-fold). However, their growth models have been different. China has stood out for the development of its manufacturing sector, driven by a policy of trade liberalisation and the attraction of foreign direct investment (FDI), a phenomenon known as the «China shock» to the global economy.2 India, on the other hand, has based its growth on the expansion of the services sector. Breaking down the growth by production factors – a procedure known as growth accounting – reveals the supply-side sources that have influenced this trajectory.

The first table presents the composition of GDP growth in India, China and a group of emerging Asian economies between 1970 and 2024, and shows the contribution of labour, capital and total factor productivity (TFP).3 The growth of output per worker is also analysed separately. China’s experience stands out for its sustained growth throughout the period. Although the (absolute) contributions of labour force growth have been similar, the growth in output per worker in China was almost double that recorded in India up until the 2010s.

- 2

See, for example, D. Autor, D. Dorn and G. Hanson (2016). «The China shock: Learning from labor-market adjustment to large changes in trade», Annual Review of Economics, 8(1), 205-240.

- 3

In India, this period can be divided between the pre-reform period (before 1991), when it was mainly dependent on the Soviet sphere, and the post-reform period, with the introduction of economic liberalisation reforms following the foreign exchange rate crisis of 1991. The swearing-in of the current leader, Narendra Modi, in 2014, has reinforced the reformist momentum. In China, this period is marked by the end of the Cultural Revolution (in the 1970s) and the reforms of Deng Xiaoping (beginning in the 1980s), the country’s entry into the WTO (in 2001) and the accession to power of Xi Jinping (in 2013).

Among the sources of growth, two distinct phases are observed. In the 1980s and 1990s, China experienced strong productivity growth, accompanied by high capital investment. In contrast, India showed a smaller contribution from capital, even compared to other emerging Asian economies, and productivity growth below 1%. Beginning in the 2000s, China saw a slowdown in its productivity growth, although capital investment remained high, accounting for between 75% and 90% of its growth in the last quarter century. In India, in contrast, there was an acceleration in both productivity and the contribution from capital.

The Indian economy in perspective

Differences in the contributions of the factors of production reflect structural transformations and reforms implemented in both countries. In the case of India, labour has made a greater relative contribution, both in quantity and quality. In terms of quantity, this is explained by demographic trends and the gradual decline in China’s labour force participation rate. On the other hand, although labour market informality has been falling in recent decades, it is still very high in India. The country has one of the highest informality indices in the region (around 80%) and a high disparity in the labour productivity between the formal and informal sectors.4 In addition, female labour participation remains low (around 30% vs. 60% in China) and a significant portion of the labour force is still in low-productivity sectors such as agriculture and construction. On the quality side, India has made great strides in education in recent decades. For instance, the adult literacy rate has risen from 50% in the 1990s to over 75% today (reaching almost 100% among young people), while the completion rate for lower secondary education has reached almost 90% among the relevant age group (compared to 60% in the early 2000s).5

- 4

See, for example, F. Ohnsorge and Shu Yu (2022), «The Long Shadow of Informality: Challenges and Policies», World Bank. Widespread informality is associated with a wide range of obstacles to development. In addition to lower labour productivity, there are also reports of reduced access to financing in the private sector, slower accumulation of physical and human capital, fewer fiscal resources, higher poverty rates and higher income inequality. Informal enterprises are, on average, less productive, employ lower-skilled workers, have more limited access to financing and lack economies of scale.

- 5

By comparison, China’s adult literacy rate had already reached 90% by the early 2000s, and the completion rate for lower secondary education has been 100% since the late 2000s.

In terms of capital, its contribution has increased steadily since the 1990s, becoming the main driver of growth. This momentum is due to the economic liberalisation reforms initiated in that decade, which stimulated both domestic and foreign investment and promoted the development of capital-intensive services. There has also been a gradual increase in public investment, financed by higher tax revenues.

Accelerating productivity in India is linked to structural reforms that have improved the allocation of resources to higher value-added sectors. Institutional improvements (such as strengthening the autonomy of India’s central bank) have contributed to a long period of political and economic stability, while the development of digital infrastructure has driven innovation and financial inclusion.

Despite the progress, India faces significant challenges. Its convergence with higher-income economies will depend on its ability to sustain the structural transformation process. This means reallocating labour to more productive sectors and advancing towards the technological frontier, especially in manufacturing. Investment in education, labour market reforms and continued institutional improvements will be critical for sustaining long-term growth. Although the contribution from capital has increased, India still has some way to go in order to harness this factor, for example by removing barriers to foreign direct investment and international trade. Such measures could provide an additional boost to the Indian economy, further supporting the growth of the second Asian giant, which aspires to be the first.