Will consumption support the US recovery in 2021?

Despite the pandemic, household disposable income in the United States not only held up incredibly well but actually grew significantly thanks to strong fiscal policy support. Will the figures for US household consumption in 2021 come as a pleasant surprise?

- Despite the pandemic, the disposable income of US households not only endured tremendously well, but increased significantly thanks to the strong support from fiscal policy. This led to an unprecedented increase in the household savings rate, which will spur consumption in 2021, when the economic revival is expected to be more sustained.

- The new fiscal package approved at the end of December, worth 0.9 trillion dollars, could also provide an extra boost to consumption in 2021, especially since around one-third will go towards direct aid for citizens.

With the announement of a substantial new fiscal package to help combat the pandemic (0.9 trillion dollars, ca. 4% of GDP), and following the sharp rise in the US savings rate during 2020, we wonder whether household consumption will rebound more strongly than expected in 2021.

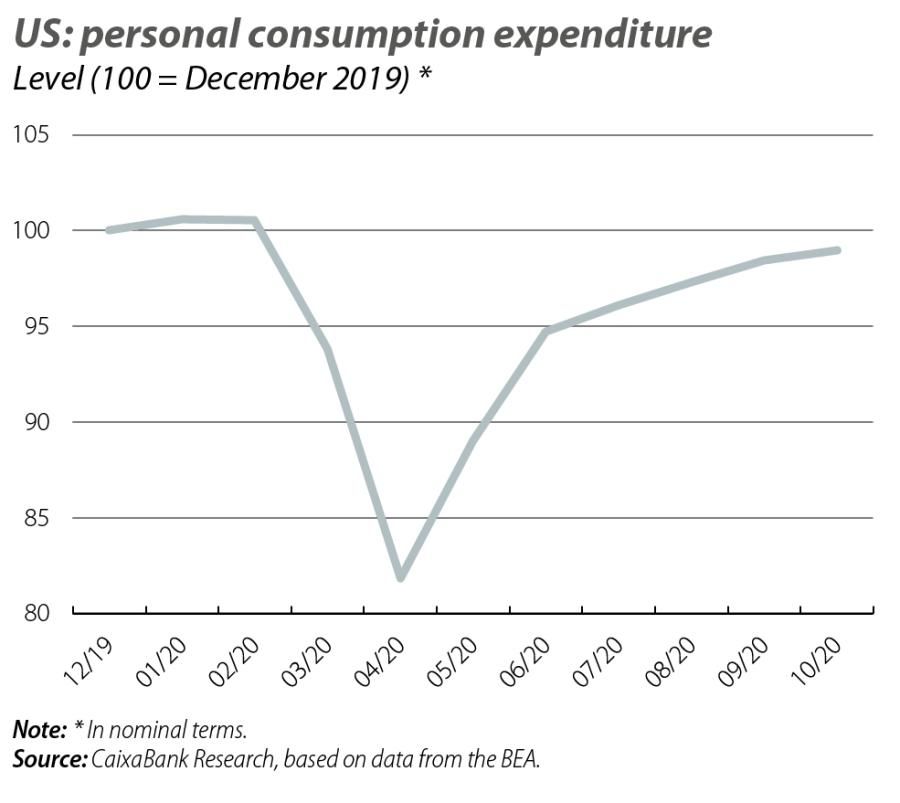

In the months of full lockdown, consumption fell sharply, partly as a result of many citizens losing their jobs, but also due to the shutdown of most leisure and recreational activities (see first chart).

Nevertheless, in this context of a large number of redundancies, household disposable income not only endured tremendously well, but increased significantly thanks to strong fiscal support in the form of direct transfers to households. Most notably, the unemployment benefit was increased by 600 dollars per week and cheques for 1,200 dollars were handed out to some 150 million citizens (see second chart).

Thus, the sharp fall in consumption and the resilience shown by income, together with the magnitude of the fiscal packages, led to an unprecedented rise in the savings rate of US households. Moreover, this increase is greater than that registered in other advanced regions: around 18 points between the end of 2019 and Q2 2020, compared to around 10 points in the case of the euro area.

Although the US household savings rate has declined since the peak reached in the spring, it still stands around 6 points above its usual level. In this regard, it is worth considering whether in 2021 American households could boost their consumption and thus provide more decisive support to the recovery of their economy.

To the extent that these savings that have accumulated in 2020 are «pent-up» savings due to the restrictions on activity and mobility, they are likely to help spur consumption in 2021, when the economy's revival is expected to be more sustained and buoyant thanks to medical advances. However, this push factor could be tempered by two elements: the high degree of uncertainty over the economic environment and the propensity to consume of those who have built up the most savings. Firstly, there is evidence that a significant portion of the accumulated savings is driven by precautionary reasons, that is, the desire to reduce consumption in order to accumulate a savings buffer in the face of uncertain employment and economic prospects. Specifically, according to a study by the Kansas Fed,1 approximately one-third of the increase in savings is due to these precautionary reasons, a factor that also tends to persist in the early stages of economic recoveries. Secondly, there are no specific data available on which groups of the US population have accumulated the most savings. However, in the United Kingdom, a Bank of England study2 shows that the accumulation of savings has been concentrated in higher-income households experiencing fewer financial difficulties, a group that also has the least propensity to consume.

On the other hand, the new fiscal package approved at the end of December to the tune of 0.9 trillion dollars could provide an extra boost for consumption in 2021. This is particularly the case because approximately one third will be earmarked for direct grants to citizens. These include the extension of the increase in unemployment benefit until mid-March (now 300 dollars per week) and the approval of a new economic stimulus cheque worth 600 dollars per person.

In both cases, these direct spending measures are lower than those approved under the previous CARES and HEROES acts.3 In addition, the experience from the measures taken under these acts tells us that a significant portion of the stimulus payments did not end up going towards consumption: according to a survey conducted by researchers from the universities of Texas, Chicago and California, 40% of households spent their entire cheque, but 20% saved it, 20% spent all the money on repaying debts, and the remaining 20% used it for various purposes.4

However, the recovery of the labour market in recent months (unemployment rate of 6.7% in November 2020, versus 14.7% in April 2020) makes it less necessary to implement fiscal aids on the scale of (or as discretionary as) those of the past. Therefore, the new package may be more likely to generate increases in consumption despite the lower amounts involved. In particular, we estimate that the contribution to GDP growth could amount to around 1%.5 This is somewhat more than we previously anticipated here at CaixaBank Research, since we were not expecting a new stimulus payment but rather other less direct forms of aid. This, coupled with the boost from part of the «pent-up» savings, could help the US economy to grow somewhat more than currently expected, provided that the pandemic is under control.

- 3. They amount to half those approved in the first rounds of aid to combat the pandemic.

- 4. See O. Coibion, Y. Gorodnichenko and M. Weber (2020). «How Did US Consumers Use Their Stimulus Payments?». Nº w27693. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- 5. We take the multipliers estimated by the Congressional Budget Office in reference to the effect of the CARES Act for the additional unemployment benefit and the stimulus payment: 0.67 and 0.60, respectively.